The Beehive Riot and The Hill

In August 1823, Mayor Josiah Quincy organized a group of law-abiding volunteers to raid the West End’s notorious center of vice, called The Hill. Two years later, North End residents formed their own posse to tear down houses of ill repute in the neighborhood, leading to what became known as The Beehive Riot.

Citizen uprisings with the intention of enforcing morality were not uncommon in early Boston. Among the first recorded incidents of civil unrest in Colonial America are the Boston brothel riots of 1734 and 1737. In contrast, the earliest years of the 19th century were relatively peaceful politically and socially, as the church and public scrutiny suppressed most crimes of vice. However, by 1820, a dramatic increase in population and the adoption of a city government led to a period of transition and upheaval.

From 1820 to 1825, Boston experienced a population increase of almost 35 percent. While previously there had been parts of town that were dotted with what was considered “slum housing,” for the first time there was now pronounced residential segregation by income, with poor and overcrowded housing concentrated in specific neighborhoods. Economic and ethnic tensions grew; brothels, gambling and drinking establishments, called “bawdy houses,” flourished; and crime increased. The North End and about four blocks of the West End called “The Hill” (including the north slope of what is now Beacon Hill) became known for their bawdy houses. Old Boston grappled with this change, clinging to norms of respectability and working to protect property values. Much of the middle class joined moral reform movements, including abolition, temperance, and anti-prostitution movements. In 1822, Boston officially became a city. The public now looked to the government to improve life and police vice.

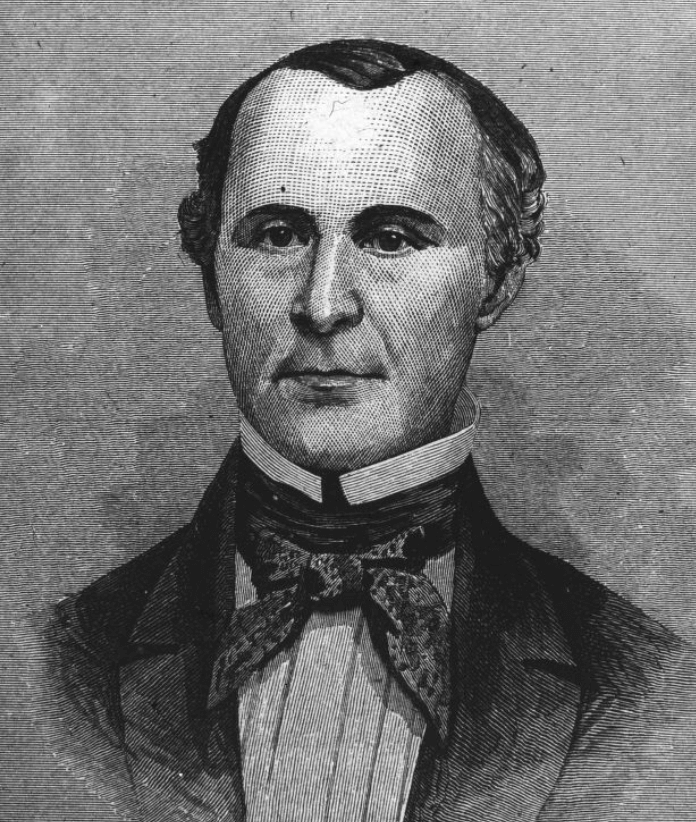

In 1823, Josiah Quincy III was elected the second mayor of Boston and promised to control the city’s criminality and immorality. According to A Municipal History of the Town and City of Boston, During Two Centuries (1852), this description of The Hill was given to Mayor Quincy soon after his inauguration:

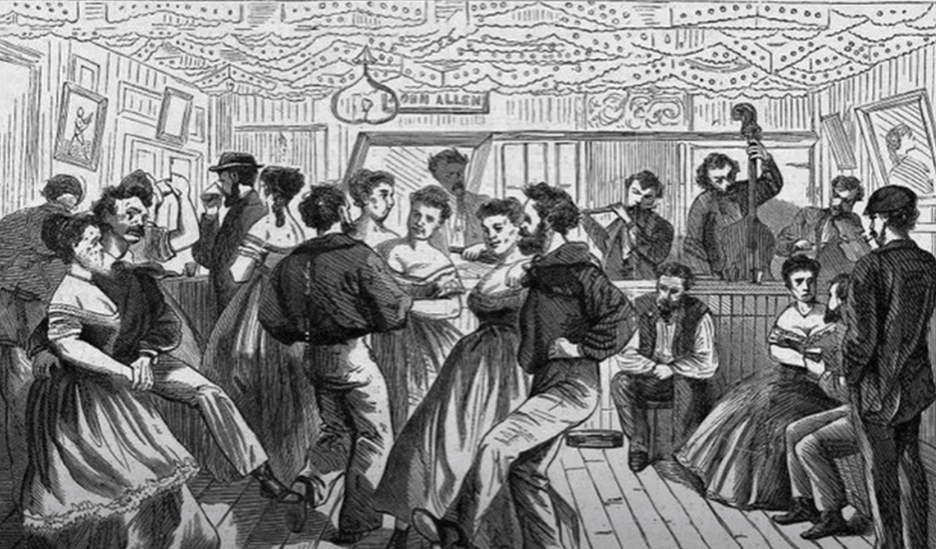

There are dances there almost every night. The whole street is in a blaze of light from their windows. To put them down, without a military force seems impossible. A man’s life would not be safe who should attempt it. The company consists of highbinders, jail-birds, known thieves, and miscreants, with women of the worst description. Murders, it is well known, have been committed there, and more have been suspected.

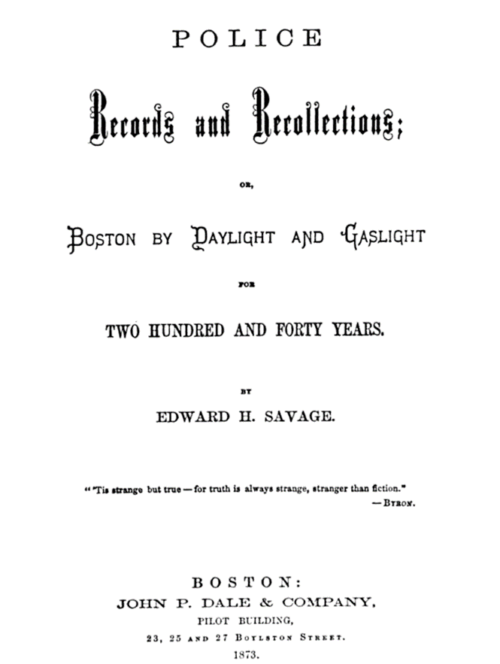

The North End and the West End were each assigned a permanent constable to patrol the streets daily, but there was particular focus on The Hill. As Edward H. Savage recounted in his 1873 Police Recollections; Or Boston by Daylight and Gas-Light: “[In 1823] ‘Shaking down’, by the girls, becomes frequent on The Hill. Mayor Quincy inaugurated stringent measures there.” Groceries and taverns had their liquor licenses revoked, dance halls were closed, and Quincy organized a posse to raid the brothels of the West End. In August 1823, over 100 people associated with the brothels were arrested and twenty-three liquor law violations were filed. Mass arrests continued into 1824.

Two years after Quincy’s raid of The Hill, rioters targeted brothels in the North End. Organized by neighborhood residents who perhaps felt overlooked after Mayor Quincy’s swift action in the West End, a mob of over 300 set out to take down two brothels, the Beehive and the Tin Pot. The mob consisted mostly of truckmen (cart drivers and stevedores) and merchants. With painted faces and pitchforks, they were able to avoid interference by constables or the mayor. The Beehive and other properties were promptly destroyed. Without an adequate police force, the violence lasted three nights until Mayor Quincy hired forty city-employed truckmen stop the raids and enforce peace. Just two lines in Savage’s Police Recollections mention the riot: “July 22. The Beehive destroyed in Prince Street, by a mob. – July 24. A riot attempted at Tin Pot, Ann Street, which was suppressed.”

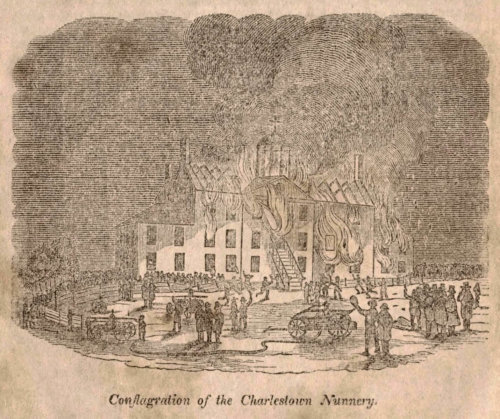

There were no reports of injury and only nineteen people connected with the riot appeared in court. They argued that the lack of prosecution of prostitutes and brothel keepers in the North End justified their actions – they were trying to save their neighborhood. Soon after the Beehive Riot, The Boston Truckmen came to be known as an organized group prone to violence. Described in 1877 as “a sort of guild who marched in Fourth of July processions attired in white frocks,” they took part in the destruction of the Ursuline Convent in 1834 and other riots. Josiah Quincy III came to be known as The Great Mayor and served until 1828. Backlash against his populism resulted in the election of Harrison Gray Otis as mayor, but mob action would remain a significant element of Boston’s politics into the early 20th century.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Hobson Barbara Meil, Uneasy Virtue : The Politics of Prostitution and the American Reform Tradition : With a New Preface (University of Chicago Press, 1990); Kennedy Lawrence W, Planning the City Upon a Hill : Boston Since 1630 (University of Massachusetts Press, 1992); Edward H. Savage, Police Recollections or Boston by Streetlight and Gaslight (Jackson, Dale and Co., 1873); James Walker, Memoir of Josiah Quincy (J. Wilson and Son, 1867); Matthew Crocker, The Magic of the Many: Josiah Quincy and the Rise of Mass Politics in Boston 1800-1830 (UMass Press, 1999)