The Edloe Sixty-Six

In 1847, sixty-six former slaves arrived at Boston’s Long Wharf. One of the group’s members, Peter Randolph, was instrumental in securing the former slaves’ freedom and the compensation promised to them. Randolph and others from the sixty-six became active members of the West End community.

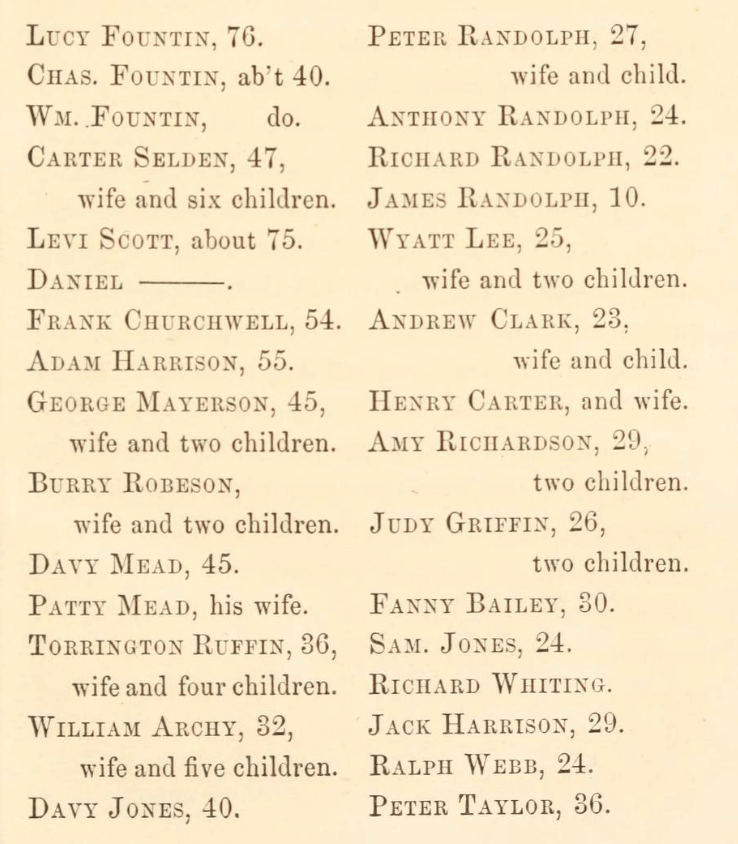

In 1844 when a Virginia plantation and slave owner named Carter Edloe died, his will stated that his eighty slaves should be set free and each given $50.00. However, the executors of the will forced the enslaved people to continue working and did not give them their money. One of Edloe’s slaves was Peter Randolph, a literate blacksmith who sought legal assistance for the group of eighty. After three years of being forced to continue to work on the plantation, they finally won their freedom. Sixty-six of the eighty, including Peter, chose to move to Boston. Though Edloe’s will stated that they were each to be given $50.00, after the executors removed their expenses from that amount, none of the sixty-six left for Boston with more than $14.96. Ranging in age from infant to 76 years old, they arrived at Long Wharf aboard the Thomas H. Thompson in September of 1847.

Most of the Edloe Sixty-Six found homes in the West End on the north slope of Beacon Hill. Names that were on both the list of the Sixty-Six and on a circa 1860 map of the West End include: Torrington Ruffin on Grove St., who arrived with his wife and four children; Fanny Bailey on Blossom Court; and Carter Selden on Southac St. (later Phillips St.), who arrived with his wife Louisa and their six children. Louisa’s mother, Lucy Fountain, was the oldest of the Sixty-Six and settled with the Seldens.

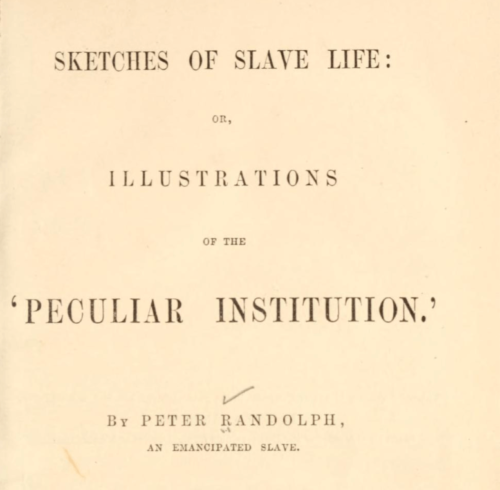

Peter Randolph was active in the city’s religious and activist communities. He became a Baptist preacher, was an active member of the Twelfth Baptist Church, and later founded the Ebenezer Baptist Church in the South End. Randolph also wrote and published Sketches of Slave Life, or, Illustrations of the “Peculiar Institution” (1855) and From Slave Cabin to the Pulpit. The Autobiography of Rev. Peter Randolph: the Southern Question Illustrated and Sketches of Slave Life (1893).

In 1855, eight years after the group’s arrival, Peter Randolph gathered the living and accounted for the deceased of the Sixty-Six and sued to reclaim what was owed to each of them per Edloe’s will. He wrote:

We were told if we came to Boston, we should be killed, or put in prison, where we should have to work under ground, or be obliged to drag carts all round the streets; but we were determined to try it, live or die. We came in 1847, and have not been eaten up yet. And now we claim the fifty dollars, and interest, since 1844.

Some of these have gone the way of all the earth: the remainder continue in Massachusetts, and are proving to the world, by their conduct, that slaves, when liberated, can take care of themselves, and need no master or overseer to drive them to their toil.

He was successful and the executors of Edloe’s will paid what was owed.

On the list of the Sixty-Six, it was the Seldens who had the largest family and received the greatest sum after winning the suit. Carter (also the name of his owner in Virginia) Selden (a prominent name in Virginia and name of the executor of Edloe’s will) was born around 1798 in Prince George County, Virginia. He found work as a porter soon after arriving in Boston. His wife, Louisa, died within three years of arriving in Boston. Supporting their six children, he later married Sarah Hazard of Kingston, RI. They had three daughters, one of whom lived only five weeks. Carter, along with some of his neighbors, voted for the first time in the presidential election of 1864.

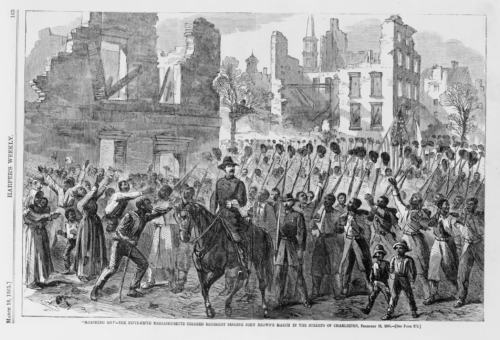

Sixteen years after arriving in Boston with his parents, Carter and Louisa’s son Thomas Selden fought for abolition as a member of the 55th Massachusetts regiment. Another son, Joseph, became a treasurer of the Twelfth Baptist Church and helped others to freedom as an agent of Boston’s Underground Railroad. A third son, Edward, was well known in the West End: he held a high position in the International Order of Odd Fellows; took in boarders, many of them from Virginia and formerly enslaved; supported his growing family as a porter and “choreman”; and became sexton of the Charles Street AME Church.

Carter Selden was still working as a porter and living at 110 Phillips Street when he died at the age of 84 in February 1882. His wife Sarah died in 1899. Members of the Selden family continued to live on Phillips, Blossom, Irving, Primus, Anderson, and Charles Streets. It is estimated that 80 percent of the Edloe Sixty-Six stayed within Boston and its suburbs.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Franklin A. Dorman and James Oliver Horton, Twenty Families of Color in Massachusetts: 1742-1998 (New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2010); Jacqueline Jones, No Right to an Honest Living: The Struggles of Boston’s Black Workers in the Civil War Era (Basic Books, 2023); National Parks Service; Peter Randolph, Sketches of Slave Life (Boston, 1855).