The Freedmen's Bureau

As emancipated men, women, and children migrated north after the Civil War, the need for Black boarding houses increased greatly. In the West End a large concentration of Black, women-operated boarding houses became home for many of these newly-freed people.

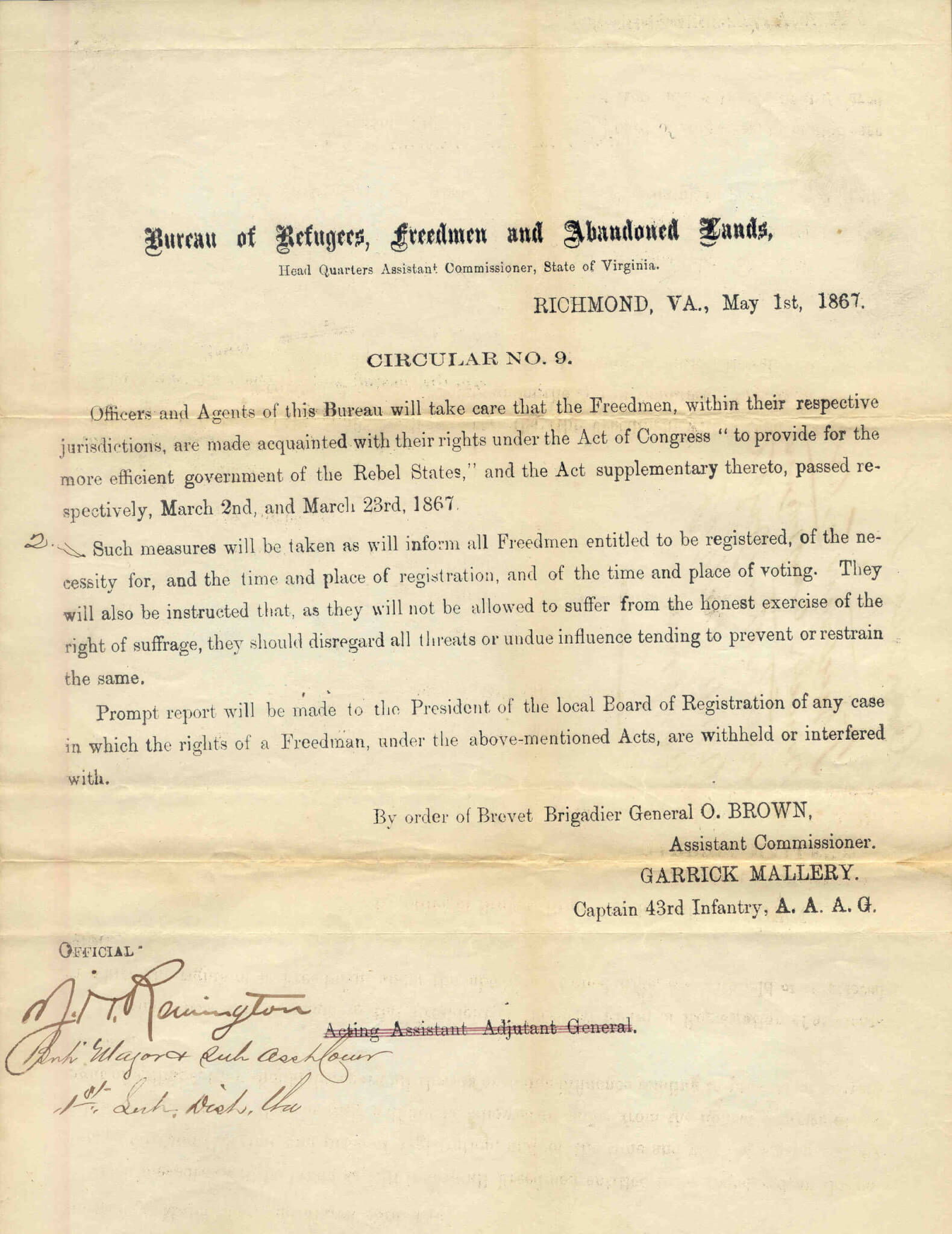

On March 3, 1865, the U.S. Congress authorized the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, as part of the War Department. The Bureau supervised and managed all matters relating to refugees, freed people, and lands abandoned or seized during the Civil War. While a majority of the Bureau’s early activities focused on the supervision of abandoned and confiscated property, its work was vital in providing relief and protecting the new rights of the formerly enslaved.

Through its transportation program, the Freedmen’s Bureau sent hundreds of freed people to Boston, mostly from Richmond, Virginia, to provide much sought after workers to fill a labor shortage. Most of these emancipated people filled domestic or general laborer positions, which became open as more women in the North took jobs in factories and as store clerks. Despite the need for workers, there was also a fear in the northern cities that emancipated Black Southerners would bring wages down by competing for jobs.

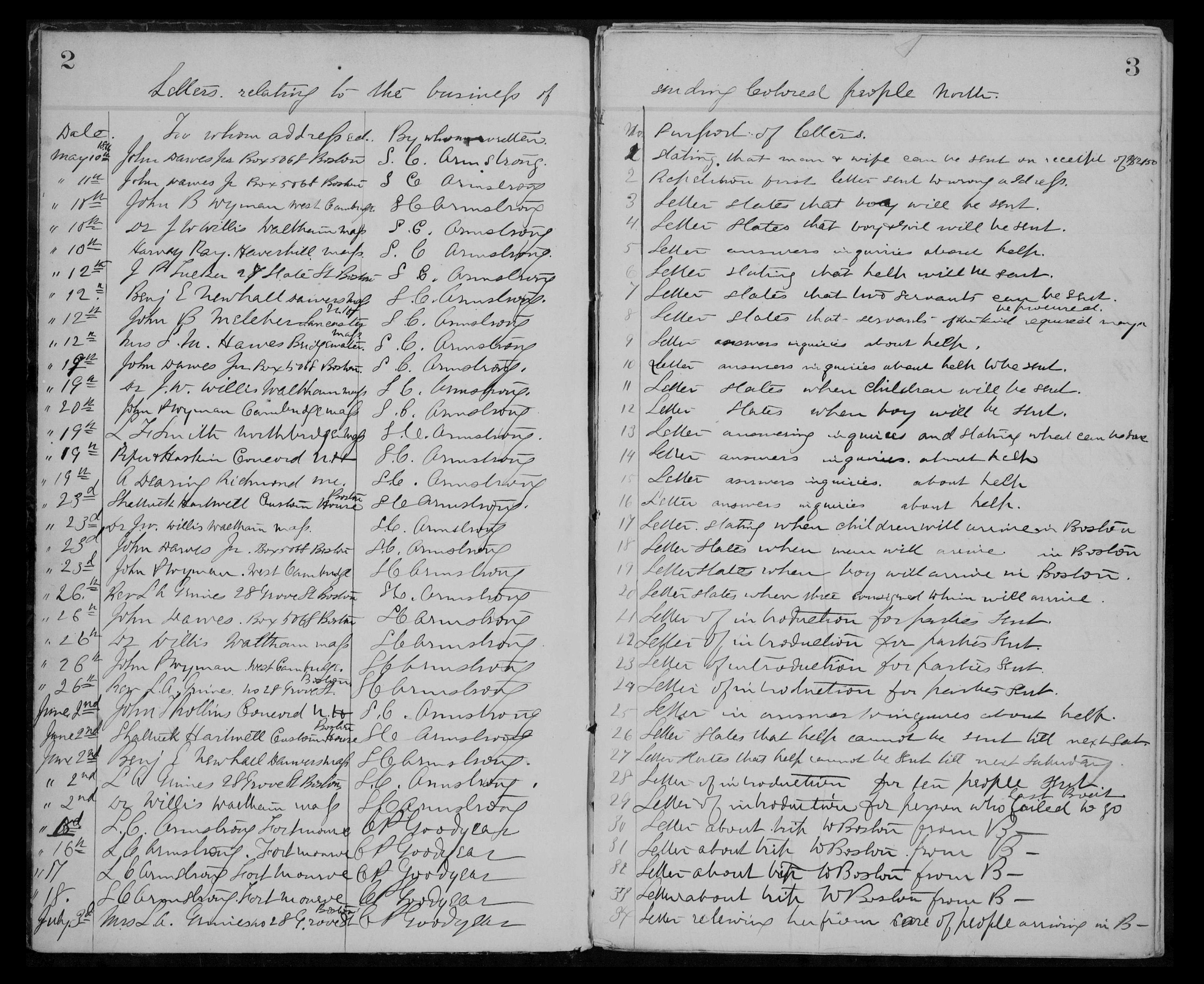

Aside from transportation, the Freedmen’s Bureau ensured employment for southern migrants, often using intelligence offices (similar to employment agencies) throughout Boston, which sold information to prospective employees new to the city and to employers in need of vetted workers. Intelligence office keepers collected a fee ranging from fifty cents to a dollar from each party who sought information, and worked in conjunction with labor agents who competed for a commission to place people in jobs. The Bureau also arranged housing for these workers in hospitable boarding houses. If needed, boarding house owners could request support through Bureau officials.

In the mid 19th century, Boston’s hotels and most boarding houses, accepted only white lodgers About 40% of Black households included boarders and the majority of formal boarding houses were run by women. The landladies whom the Freedmen’s Bureau relied upon, were often themselves emancipated migrants from the South, who took extra responsibility for the welfare of their boarders by ensuring that their employers treated them fairly. One such landlady was Harriet Bell Hayden.

Hayden provided the often invisible labor necessary to support both the antebellum abolitionist movement and the migration of freed people after the Civil War. The wife of prominent abolitionist Lewis Hayden, with whom she self-emancipated in 1844, Hayden ran a boarding house from her home at 66 Southac Street (present day Phillips Street). The Hayden home was the most active Underground Railroad safe house in the city before Emancipation, boarding up to thirteen relocated men, women, and children at a time. With the help of an Irish domestic, Harriet cooked meals, cleaned, managed all aspects of the home, and helped to arrange employment for the migrants.

Maria Smith was the proprietor of an intelligence office at her home on Sears Place, off Anderson St., and took in migrants as needed. While she worked to match freed people from Virginia and Washington, D.C. with employers in Boston, her husband H.L. Smith worked in Washington, D.C. Though it was necessary to take in boarders occasionally, Maria did not wish to run a boarding house and was looking forward to the opening of the Joy Street Freedmen’s Asylum in 1867.

In spring of 1867, the Freedmen’s Bureau provided funding from its Transportation Office to prepare a house at 67 Joy St. to become the Joy Street Freedmen’s Asylum, a temporary home for the newly freed migrants from the South. Unfortunately, the Bureau ceased supporting the transportation program in 1868 and the asylum house project died. The Bureau itself, unable to address the needs and prospects of millions of freedpeople, shut down in 1872. The house at 67 Joy St. would become an intelligence office run by Louisa Robinson Pitts, and later a medical practice run by Rebecca Lee Crumpler.

While the Freedmen’s Bureau no longer arranged travel for migrants, Black southerners continued to move north and often found companionship and mutual support in the boarding houses of the West End. Boarding offered a means for new arrivals to become acclimated to life in Boston, and provided economic opportunities for women. Through the hard work of boarding and arranging employment for the newly free, while also overseeing family life, women like Harriet Hayden combined work in the home with social activism. Despite political and economic marginalization, such women were true community builders in postbellum Boston.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Bob Potenza.

Sources: Gamber, Wendy. The Boardinghouse in Nineteenth-Century America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.; Horton, James Oliver and Lois E. Black Bostonians. Holmes and Meier, 1999.; Jones, Jacqueline. No Right to an Honest Living; The Struggles of Boston’s Black Workers in the Civil War Era. Hachette Book Group, 2023.; National Archives;

National Parks Service.