The Hidden History of Pemberton Square

Bostonians familiar with the demolition of the West End may not know how another once-prominent location in the city disappeared from the map. This spot, located on Beacon Hill, was designed for the homes of wealthy Boston families, and was established at about the same time as another famous residential location further down “the Hill.” But, unlike Louisburg Square, which is today synonymous with old Brahmin Boston, Pemberton Square remains largely forgotten, its remnants barely visible.

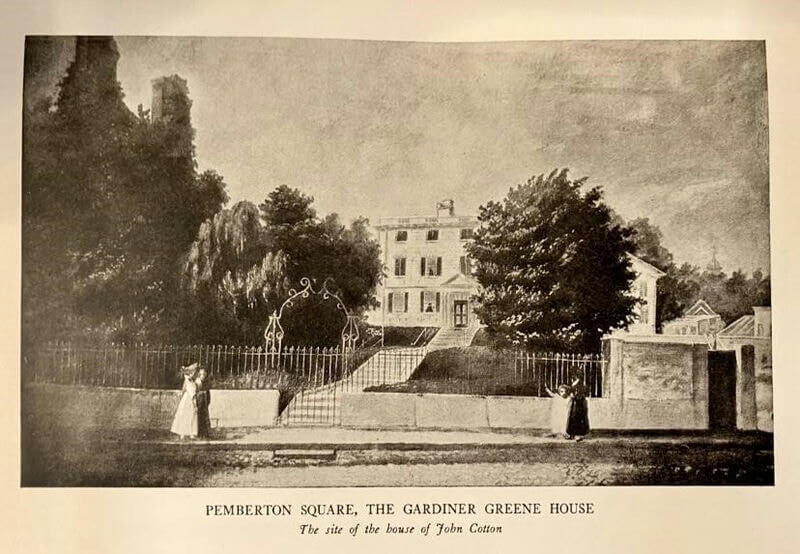

Pemberton Square began when Patrick T. Jackson, merchant, and founder of the Boston Manufacturing Co., commissioned the flattening of the top of what was then called Cotton Hill, located between Tremont and Somerset Streets. According to Phebe S. Goodman’s The Garden Squares of Boston, this took fewer than six months and was completed in October 1835. Landscape architect Alexander Wadsworth planned the development of the property and architect George Minot designed the homes that were built around the square. Goodman noted these homes “would be consistent in style and ornamentation.”

In 1838 the city named the site Pemberton Square, even though a square at the foot of the hill already held that name. That lower square was renamed Scollay Square after William Scollay, a local developer who had built a home where Congress and Court Streets met. The creation of Pemberton Square and Louisburg Square was characterized by some as a response to the population growth of the old Boston peninsula. Michael Holleran referred to these areas as “urban densities” in his book, Boston’s “Changeful Times.” He wrote that residents like Jackson were looking for “elite residential areas” that would not be subject to overpopulation. While perhaps not as prestigious as Louisburg Square, the homes in Pemberton Square were, as Edwin M. Bacon wrote in Bacon’s Dictionary of Boston, “fine, indeed elegant for their time, and for many years it was the residence of some of the most substantial citizens.” Bacon also noted that many prominent citizens established their offices in Pemberton Square, which were joined by “a number of city and state offices, notably the headquarters of the board of police commissioners.”

While Louisburg Square established itself as Boston’s finest neighborhood, Pemberton Square failed to sustain itself as a wealthy residential enclave. As it became home to more legal and commercial offices, city leaders began considering a reimagined square that could house a new county courthouse. As wealthy residents moved to more fashionable residential areas, such as the Back Bay, nearby Scollay Square began to backfill with a more questionable element. Historian Thomas H. O’Connor may have summed up Scollay Square’s transition best in his book The Hub: Boston Past and Present, “The square had become a place where tattoo parlors, barrooms, shooting galleries, shabby movie theaters, hot dog stands…and sleazy burlesque houses blighted what had once been a historic district.” O’Connor noted that sailors docking in Boston during World War II would often ask the question, “Where’s Scollay Square?” as they took shore leave looking for fun in the city.

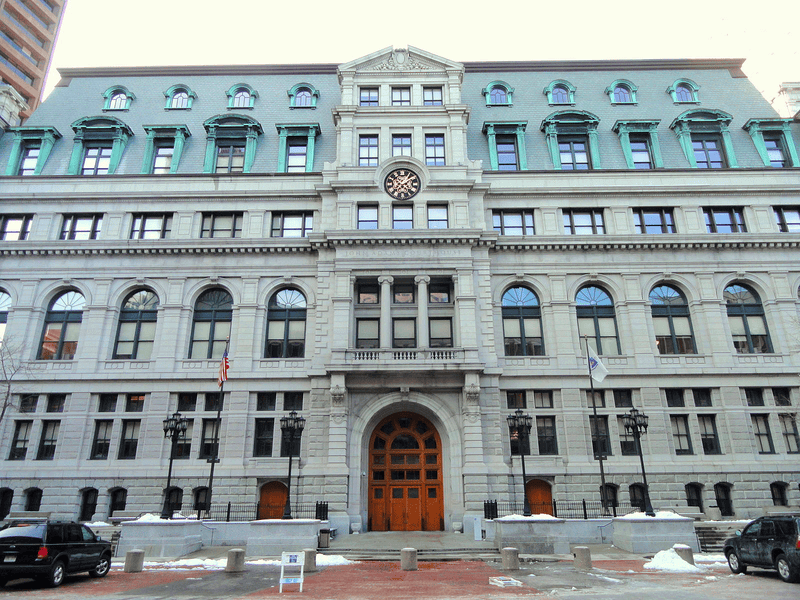

In 1885, Pemberton Square’s demise began. The homes on the west side of the square were demolished to make way for the new Suffolk County Courthouse (the building now known as the John Adams Courthouse, home to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.) While generally considered a beautiful building in its own right, it dramatically and permanently altered the makeup of the neighborhood. The construction not only destroyed half the homes on the square, it removed its central garden space. The last of the remaining buildings were razed in 1969 to make room for the long, curved Center Plaza that now looms over Government Center—the urban development project that wiped out Scollay Square.

Most of what is left of the original Pemberton Square is the brick courtyard between the courthouse and Center Plaza. It was through litigation over the easements of original development that the courtyard remains open today. In “Changeful Times,” Holleran noted that “it was mutually agreed, in the strongest and most unmistakable terms… that certain areas shall remain forever open, including the front ten feet of the courthouse lots.” Today, that open space is a pathway filled with people coming and going from the original courthouse and its more modern cousin next door. Only the most ardent Boston historians have any inkling of the grandeur that once existed on that land and what it represented for a growing and maturing city.

Article by Marshall Hook, edited by Bob Potenza

Source: Bacon, Edwin M., and George Edward Ellis. Bacon’s Dictionary of Boston. Houghton, Mifflin and Co, 1886.; Goodman, Phebe S. The Garden Squares of Boston. 1st ed., University Press of New England, 2003; Holleran, Michael. Boston’s “Changeful Times”: Origins of Preservation & Planning in America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998; O’Connor, Thomas H. The Hub: Boston Past and Present. Northeastern University Press, 2001.