The Leverett Street Almshouse

For almost twenty-five years, the Leverett Street Almshouse dominated Barton’s Point, a blunt strip of land jutting out from the West End into the Charles River. In this building, designed by Charles Bulfinch, Boston continued to carry out its tradition of housing and caring for its most needy residents.

From the earliest days of the Town of Boston, English Puritans acknowledged a collective responsibility for providing assistance to those unable to care for themselves, despite their strong commitment to a Calvinist work ethic. This realization was grounded both in their religious beliefs and a practical desire to maintain order in the town and the Massachusetts colony at large. Though the colony’s first governor, John Winthrop, applauded a charitable spirit within individuals, he believed a centralized system was needed to care for the “deserving poor” and to “correct” the “vagrant and dissolute persons” by encouraging them to work. Beginning in 1639, the colonial leadership mandated that town governments had to manage care for their needy residents, usually by enlisting volunteer families who were compensated by the town for their expenses. This system proved unsustainable as Boston grew numerically and economically, and attracted more outsiders in search of economic opportunity.

Boston opened the first Almshouse (“alms” meaning money for the poor) in North America in 1664, near the intersection of modern day Beacon and Park Streets. Funding for construction came mainly from private donations, but operational costs depended upon tax dollars. The purpose of the almshouse was to offer shelter and relief to the “aged and infirm poor” or neglected children of the town. Other inmates, “guilty” of bringing about their own misfortune through drunkenness or slothfulness, or having committed minor crimes, were coerced to enter the almshouse in order to “clean up the streets.” When possible, all almshouse inmates were expected to work to earn their keep. As time went on, almshouse admissions would include more immigrants and freed slaves.

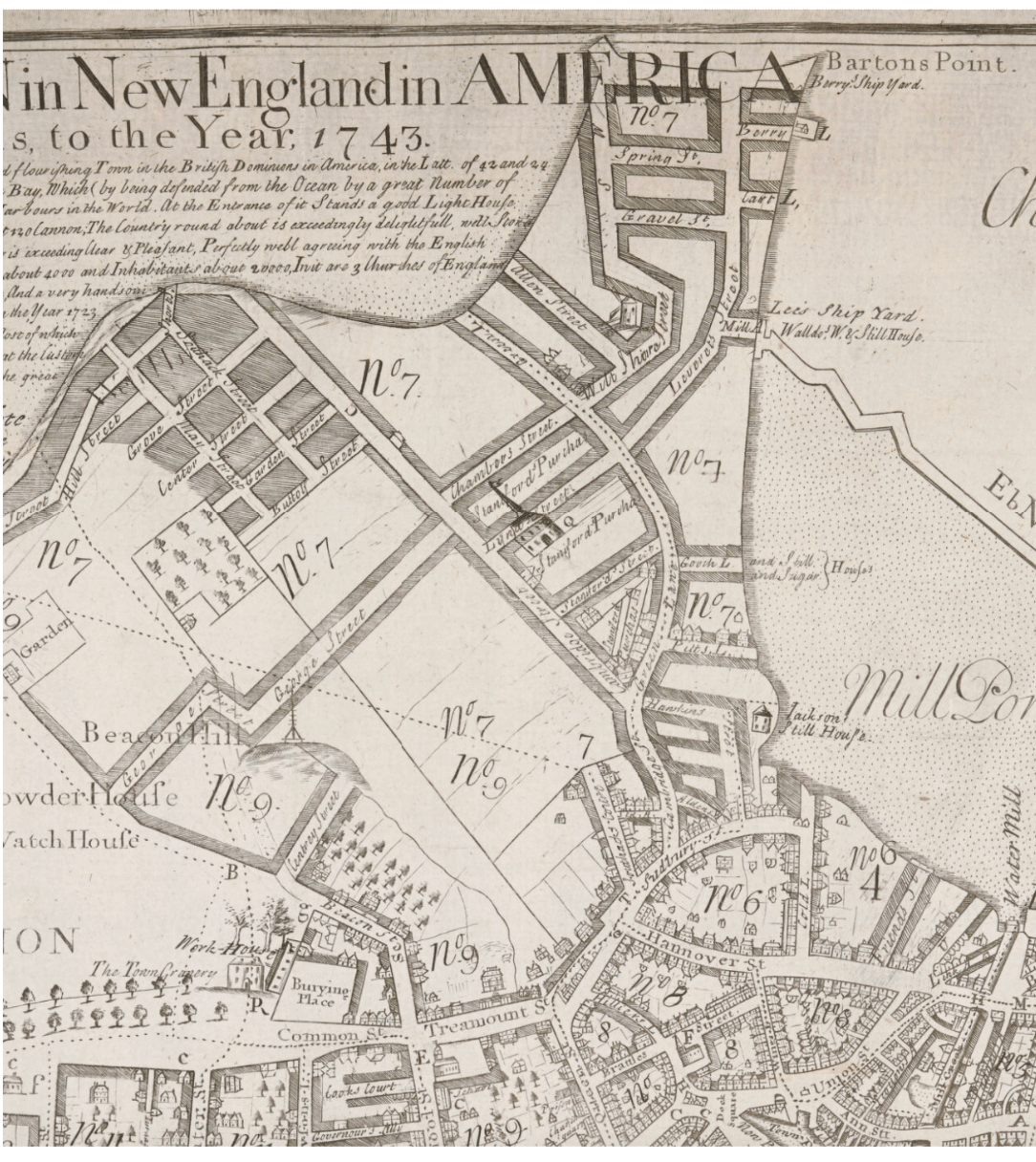

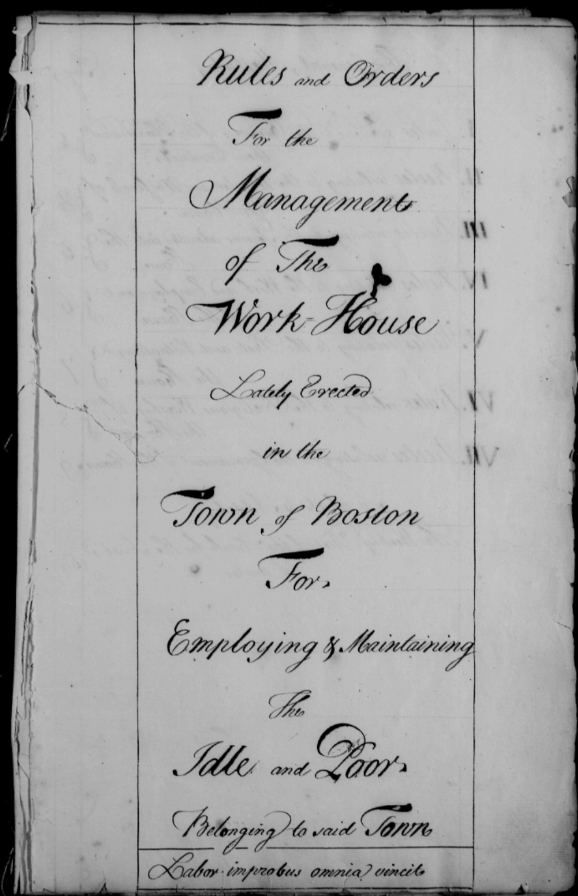

A second almshouse, two-stories tall and made of brick, replaced the original in 1686 at the same location after the first succumbed to one of Boston’s frequent fires. In 1692, the Massachusetts General Court (i.e. legislature) established the Overseers of the Poor, a quasi-governmental agency mandated with the management of all public assistance programs throughout Massachusetts. For over 100 years, under this authority, the Almshouse expanded to meet the growing demands of Boston, with the addition of Bridewell Prison (1723) and a workhouse (1739). Despite these enhancements, the almshouse could not keep up with the increasing rate of admissions to the “ancient brick building in Beacon-street.” At the same time, the recently completed State House on nearby Beacon Hill and plans to develop this area into a fashionable neighborhood convinced leaders to build a new almshouse outside of the town center.

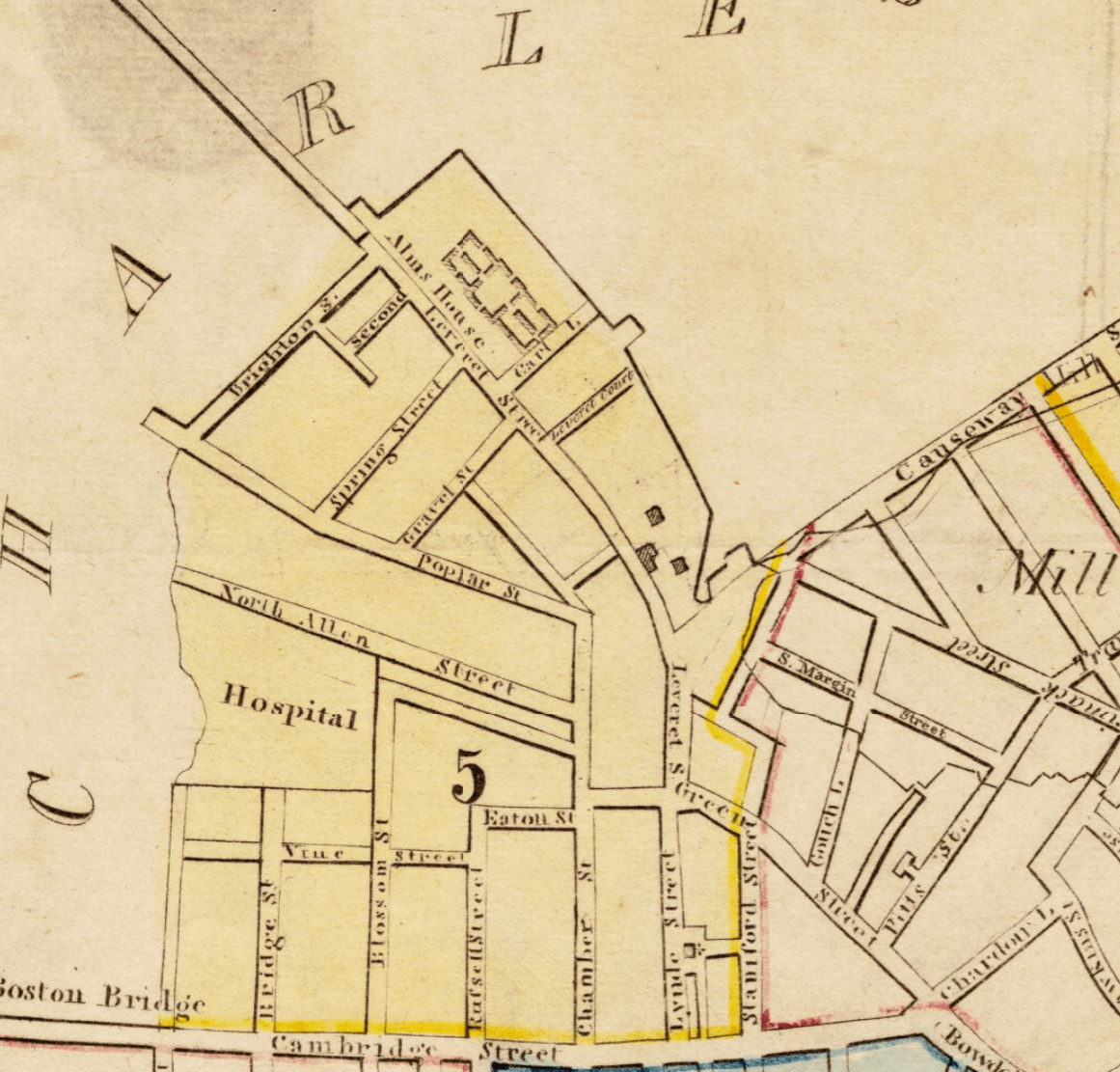

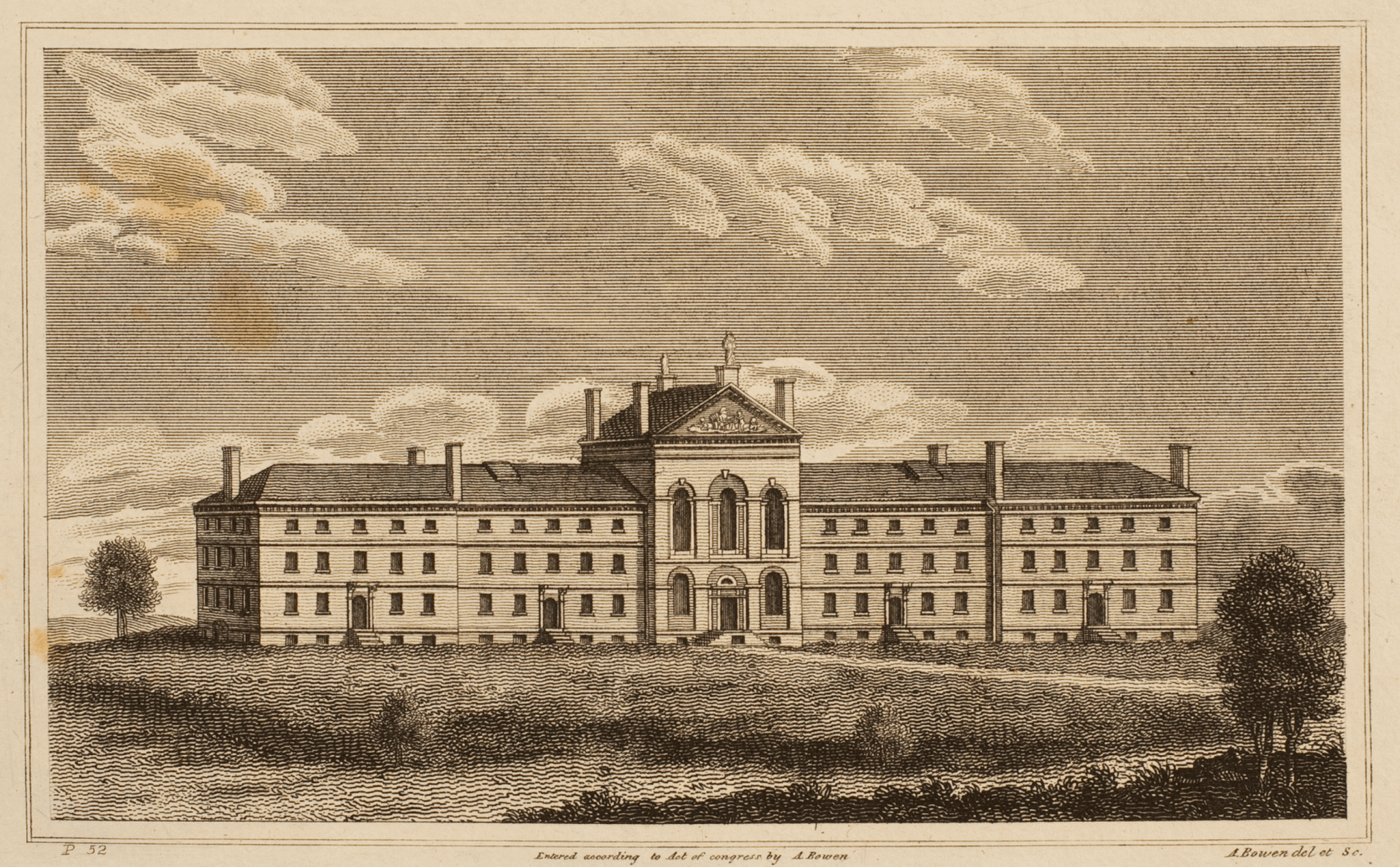

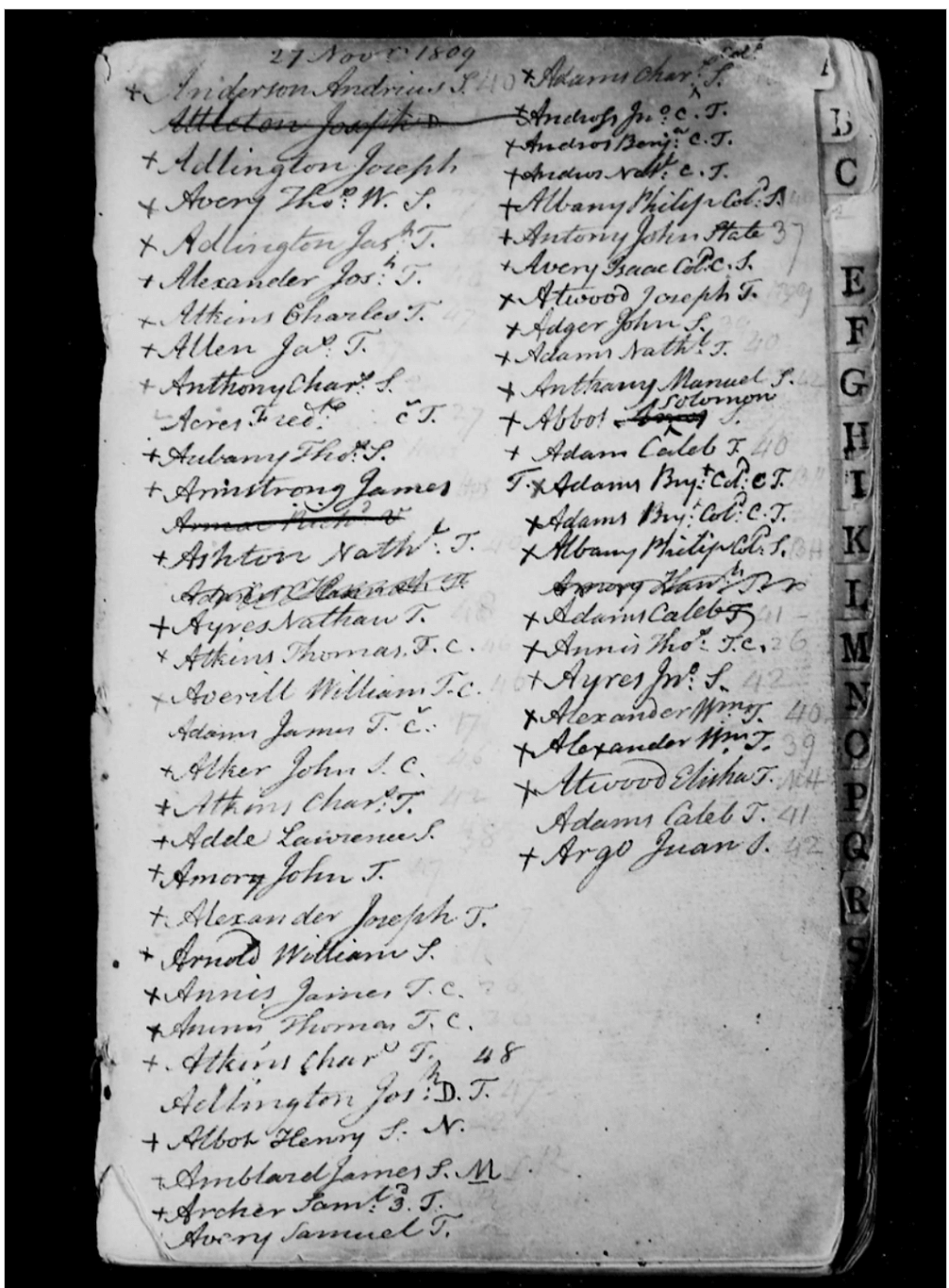

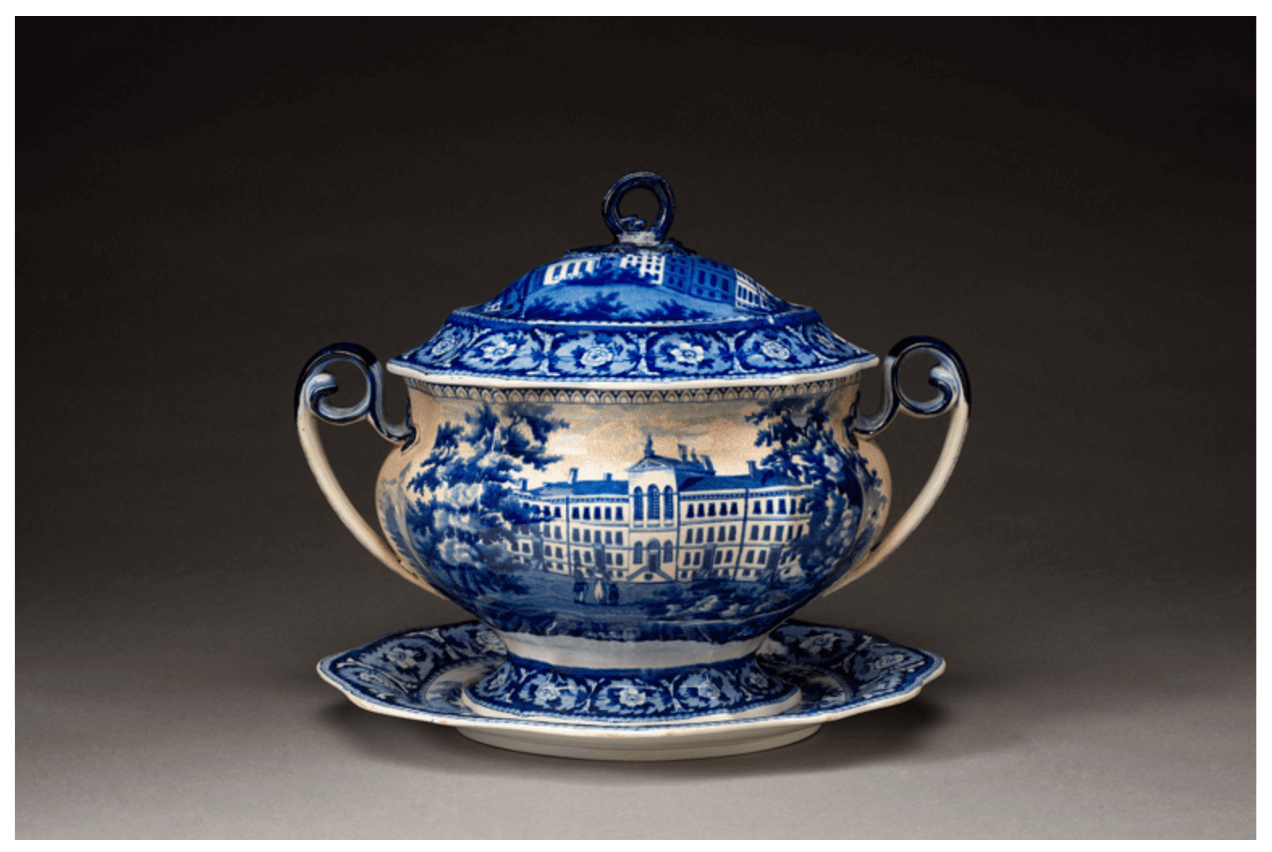

Forever looked upon as the fringe district of Boston, the West End was unsurprisingly the chosen location for a larger, modern almshouse. The town selected Leverett Street on Barton’s Point, the northernmost section of the West End along the Charles River, as the site, and Charles Bulfinch, architect of the State House, provided the design. Construction began in 1799 and took two years to complete at a cost of $50,000, funded mainly by the sale of the land from the original almshouse. Dubbed the Leverett Street Almshouse, the impressive structure was pronounced one of Bulfinch’s most significant public buildings, featuring a “Classical-style façade” and “large arched windows… finished with fluted pilasters of the Ionic order” and surrounded with brick walls and an “handsome gate.” It consisted of four floors containing forty-eight rooms. Most rooms were for living quarters which were segregated according to race, gender, and age. Two rooms were used for medical quarantine and another two for psychiatric patients or “maniacs.” Others held the kitchen and utility areas, offices, two hospital wards, nurseries, and two schoolrooms.

Improved record keeping during the twenty-five-year existence of the Leverett Street Almshouse provides interesting insight into life within such a facility. Though it housed some long term residents, especially the aged and incapacitated, most inhabitants came and went, depending upon economic conditions or personal circumstances. Men came and left the facility with much more frequency; women, often with children in their care and fewer employment opportunities, found themselves more often in need. Ruth Wallis Herndon, author of “Poor Women and the Boston Almshouse in the Early Republic,” explains that it was the longer term female occupants of Leverett Street who created a unique culture of community care within the facility, and though nominally controlled by male directors and staff, it was women who actually kept the almshouse running.

Within its first year, the Leverett Street Almshouse had already reached a maximum capacity of 400 residents, foretelling its relatively short lifespan. Though there was hope that it would be able to accommodate the special needs of each demographic of the poor within its walls, housing the aged, disadvantaged children, permanently disabled, mentally ill, and criminal in such close proximity prevented each group from being optimally cared for. In the end, two main factors brought about the decision to close the Leverett Street Almshouse for good in 1825: the city decided to focus on more affordable workhouses, which had proven successful in towns like Salem, and, as in the prior case of Beacon Hill, rising property values in the West End made the area more desirable for residential development. The almshouse was replaced with a dedicated workhouse in South Boston.

Though almshouses may have gone out of fashion as an effective and economical method for caring for society’s underprivileged, they are an important symbol of Boston’s historical commitment to providing important services to its citizens.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Colonial Society of Massachusetts, “The Almshouse and Workhouse”; Colonial Society of Massachusetts, “The Historical Setting: The Boston Poor and the Records of the Overseers”; Five Colleges and Historic Deerfield Museum Consortium, Collections Database; Ruth Wallis Herndon, “Poor Women and the Boston Almshouse in the Early Republic,” Journal of the Early Republic 32, no. 3 (2012): 349–81; Isabella, Lily, Sofia, “The Boston Almshouse,” Clio (November 13, 2018); Harold Kirker, The Architecture of Charles Bulfinch (Boston: Harvard University Press, 2013); Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston Overseers of the Poor Records; Report of the Committee on the Subject of Pauperism and a House of Industry in the town of Boston (1821); The Workhouse.