The Middlesex Canal

Two hundred years before construction began on the Ted Williams tunnel, businessmen in post-revolution Boston sought to improve upon dirt and gravel paths used to bring inland goods to the growing port city. The result not only helped New England become an economic driver in the early 19th century, but acted as a blueprint for future engineering endeavors in the young United States of America.

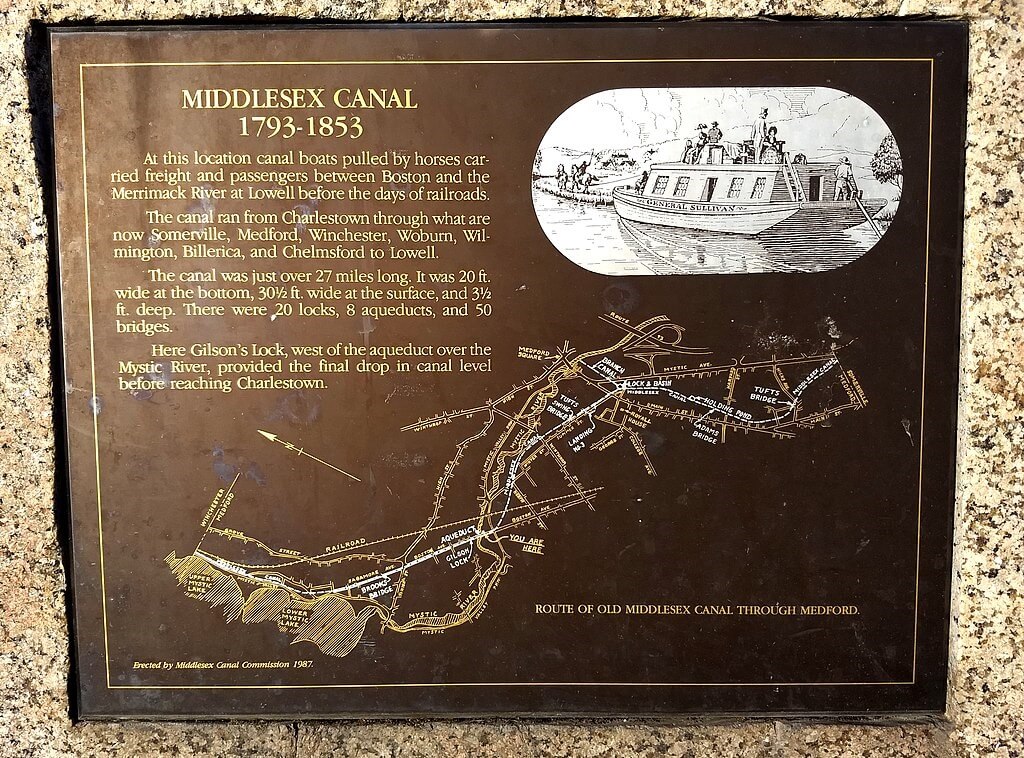

The Middlesex Canal was a 27-mile barge canal constructed between 1794 and 1803 connecting the Merrimack River at East Chelmsford, MA, through Boston’s West End to Haymarket Square and eventually, Boston Harbor. The canal was one of the first of its kind in the newly independent United States, and drove the industrialization of the Merrimack Valley. Before the advent of the railroad, water transport was the most efficient method of shipping goods – a wagon team of oxen could pull only 3 tons, while a single horse could lead 30 tons along a canal towpath. Low-cost transport became essential as Boston’s economy continued to grow, stimulating demand for both raw materials and new markets for the goods produced within the city.

The Middlesex Canal Corporation was chartered on June 22, 1793, only a decade after the last British soldiers left New York after the Revolutionary War. The canal stood to significantly enrich Boston’s maritime trade and benefit growing farming and raw material industries to the north. Accordingly, the endeavor found financial support from the day’s prominent Massachusetts statesmen, including John Adams, John Quincy Adams, John Hancock and former attorney general James Sullivan. While investors were abundant in the area, “in 1793 there was not one trained civil engineer among all the citizens of the United States”. Across the Atlantic, Britain was in the midst of a canal building explosion to support their nascent industrial revolution. The Middlesex Canal Corporation enlisted British canal engineer William Weston to plan the canal’s route through the New England countryside.

Weston surveyed the area alongside Loammi Baldwin, former continental army colonel and cabinetmaker. The two found the landscape “favorable for cutting, being chiefly sand and peat…(with) few or no instances of canals of the same length…conducted in ground as favorable as this”. Through purchase, gift, or eminent domain, the corporation procured 142 parcels of land along the future development site. Nearby landowners and farmers acted as the canal’s construction crew, breaking ground on September 10, 1794. The original ditch measured 30 feet in width and 3 feet in depth, flanked by a towpath to allow horses and oxen to transport goods over the 27-mile route. Just like Boston’s Big Dig, the ambitious project was fraught with cost overruns. Stonework for the 20 locks along the canal proved costly; large boulders along the route had to be hauled away and embankments frequently collapsed requiring constant rebuilding and repair. The canal finally opened for business in 1803.

The boats that traversed the canal were custom-built to meet canal regulations, possessing a 75-foot length limit to fit into lock chambers and a 9.5-foot width limit so boats could pass on the water. The canal quickly became a highway for 30-ton barges carrying a wide variety of goods. Lumber from New England forests fueled both construction and industry in markets across the Merrimack Valley; sand from New Jersey was shipped up the river to a newly opened glass factory at the canal’s end at the Merrimack River; and tree bark from forests in New Hampshire were used in the tanning process to fuel Woburn’s leather industry. Finally, bricks formed from Medford’s clay pits were sent both north and south for use in countryside estates and city towers alike. The corporation estimated the canal cut shipping costs by up to 75% as the 27-mile journey was cut from 4 days over land to 12 to 18 hours by water.

The Boston terminus met the harbor near Charlestown, where land reclamation had filled in much of the modern-day area. Agricultural goods and raw materials flowed into the harbor, driving population growth in the city from 24,937 citizens in 1800 to 136,881 in 1850. Granite blocks used in the construction of West End buildings, including Mass General Hospital, were sent on barges down the canal. Goods manufactured both in Boston and imported from other states and countries were shipped north to cities along the canal route. Perhaps most importantly, the relative ease of transport helped cement Boston as a major Trans-Atlantic shipping hub in the northeast.

While the Middlesex Canal officially ended on the Charlestown side of the Charles River, city planners incorporated the success of the waterway during the Mill Pond’s transformation into the Bulfinch Triangle. The canal carved into the city landscape along Canal Street allowed boats to deliver goods into the city center. The area also became “the city’s gas station,” as hay from northern farms fed the horses which transported people and goods through Boston’s winding streets. Eventually, the open intersection of Merrimack, Charlestown, and Canal Streets adopted the name Haymarket Square based on the canal’s inland purpose.

The canal was a definitive engineering achievement of its day. William Weston introduced new surveying instruments into the American engineering profession which were later studied by builders of the Erie Canal completed in 1825. Loammi Baldwin imported volcanic ash from St. Eustatius in the Dutch West Indies in order to create a watertight cement for the lock system, revolutionizing the commercial cement industry. Finally, a floating towpath system featuring an underwater drawbridge system allowed the canal to traverse ponds and other bodies of water along the route. As in England, another engineering achievement – the steam locomotive – ultimately resulted in the Middlesex Canal’s demise. A team of surveyors led by Loammi Baldwin’s son proposed a route for the Boston and Lowell railroad closely following the canal’s path, and the railway opened for business in 1835. Over the next two decades, rail cars carrying 300-ton loads rendered the 30-ton barges on the canal obsolete – a passenger train could make the trip in only 70 minutes. The last toll on the canal was collected in 1850 after nearly half a century of service.

The Middlesex Canal was a key to the growth of Boston during its operation, acting as a man-made river providing transportation, raw materials, and consumer markets for finished products along its path. The everyday lives of 19th century inhabitants of the West End surely would have felt its effects, as they enjoyed foodstuffs from Tewksbury, window glass from Chelmsford, and textiles from Lowell. The canal’s route also crucially provided the groundwork for later rail infrastructure, continuing the Bulfinch Triangle’s importance as a shipping and manufacturing hub that employed many of the West End’s working-class residents in the late 19th century.

Article by Meyer Aviles , edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: https://americanhistory.si.edu/america-on-the-move/transportation-1876; https://charlestownbridge.com/2019/04/20/historic-house-of-the-month-middlesex-canal-houses/;https://libguides.uml.edu/early_lowell/Boston_and_Lowell_RRhttps://libguides.uml.edu/middlesex_canal; https://today.emerson.edu/2016/07/13/professor-emeritus-dahill-91-paints-a-picture-of-history/; https://www.medfordhistorical.org/medford-history/about-medford/the-middlesex-canal/; http://www.middlesexcanal.org; https://www.newenglandhistoricalsociety.com/middlesex-canal-americas-1st-superhighway/; http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A2001.05.0303%3Achapter%3D1%3Apage%3D1