“The Opera Ejection Case”: Sarah Parker Remond, The Old Howard, and Segregation in Antebellum Boston

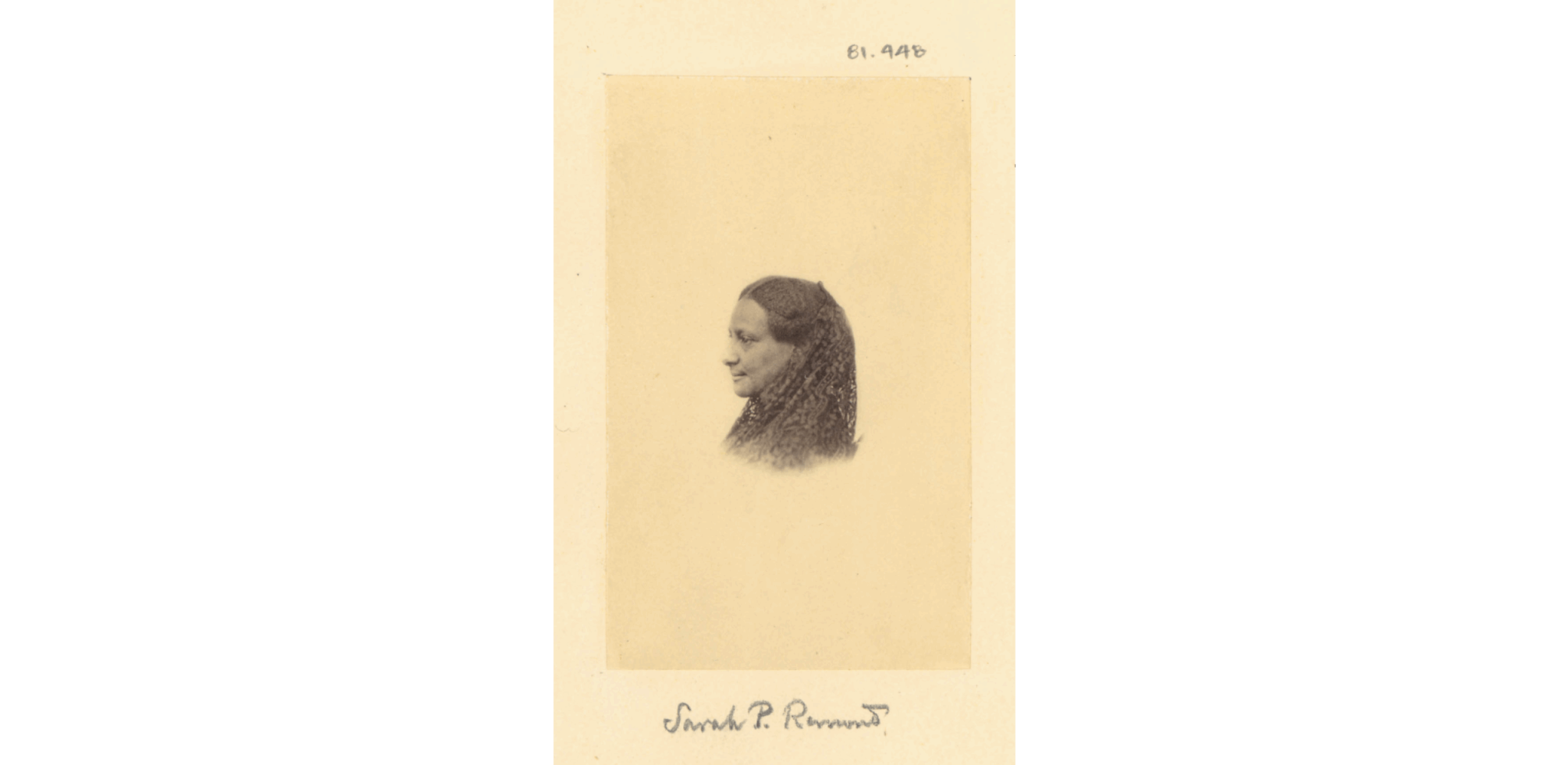

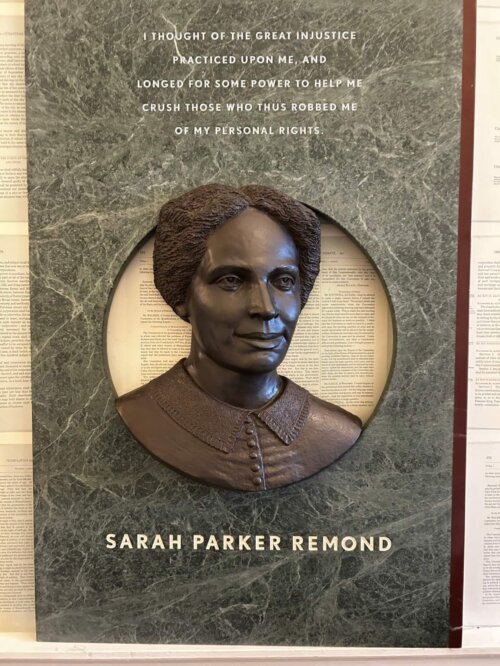

When abolitionist and early civil rights advocate Sarah Parker Remond (1824-1894) was kicked out of an opera at the Howard Athenaeum due to her race, she went to the courts seeking justice. Her case brought issues of segregation and discrimination in nineteenth century Boston into the spotlight.

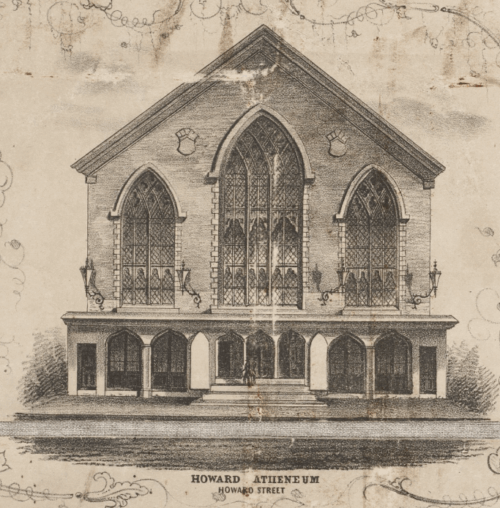

One hundred and two years before Rosa Parks’s act of civil disobedience that sparked the Montgomery bus boycott, a similar scene played out at the Howard Athenaeum. Three black patrons, Sarah Parker Remond, her sister, Caroline Remond Putnum, and William Cooper Nell were roughly kicked out of the theatre after refusing to give up their seats.

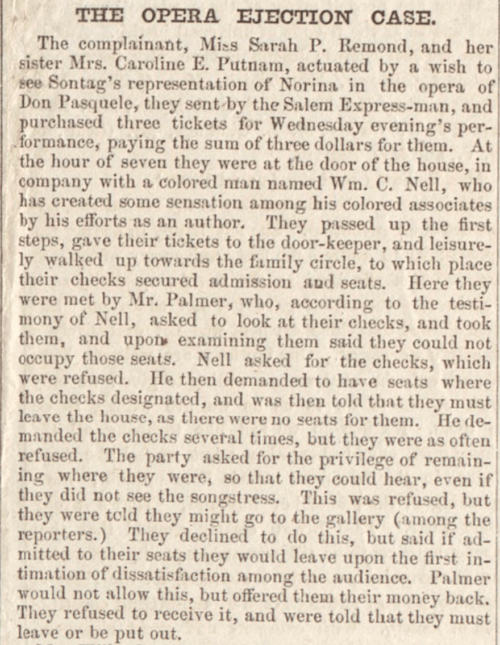

On May 4, 1853, Remond and her companions went to the opera. They had purchased $1.00 tickets in advance to have seats in the “family circle” level, which were expensive and desirable. As they attempted to sit down, a manager for the opera, Henry Palmer, stopped them. He would not allow them to sit with white patrons and instead directed them to the gallery seats, where the Black audience was expected to sit. Massachusetts did not have laws requiring segregation and other theaters in Boston had integrated seating. However, the opera company that was renting the Howard did not want a mixed crowd.

When the Remond party refused to move, Palmer called for backup and a Boston police officer, Charles Philbrick, arrived. He began forcing the party out, tore Remond’s dress, and pushed her down the stairs, which injured her shoulder. After her “ejection from the opera” as William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator described it, Remond fought back in the courts. She had been raised with a commitment to advocating for Black rights, including her own. In a speech she gave in Scotland a decade later, Remond explained the “demoralizing and degrading” effects of slavery and racial discrimination “not only on the slaves themselves, but on free coloured men and women, and on white men in the slave States.” She was not going to let those effects stand in Boston. Not if she could help it.

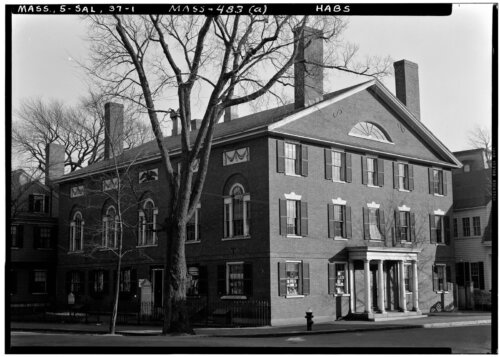

Remond was born in 1824 to a large family of free Black entrepreneurs in Salem, Massachusetts. Her family moved to Newport, Rhode Island after she and her siblings were denied access to public education in town where they were able to attend a private school for Black children. Remond and her relatives were active in the women’s anti-slavery circles and their home was at one point a stop on the underground railroad. Her older brother Charles Lenox Remond was also a well-known abolitionist. He spoke in front of a Massachusetts House of Representatives committee to protest segregated rail cars. With her family history, Remond was more than prepared when she brought her complaint against Palmer and Philbrick to court.

The case came before Judge Thomas Russell. Testimony from Black patrons of other Boston theaters, convinced Russell that there was no prevailing custom against integrated seating. Thus Remond had every right to expect that she would be seated in the spot she paid for. The opera had essentially broken its contract with a paying customer. However, the Judge determined the issue was that the theater had not given notice that it would be segregated. In other words, segregation would have been allowed, if properly advertised. Russell still ruled in Remond’s favor, granting her $500 in damages. The Howard also apologized by offering her and her sister equivalent seats to the ones they had originally paid for. Nevertheless, segregation at the Howard continued with an added sign to advertise separate seating for Black patrons.

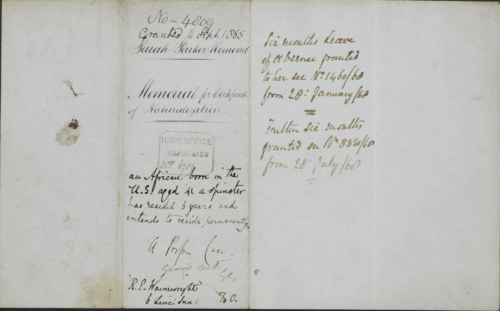

Remond went on to have a successful career as an abolitionist lecturer and advocate for civil rights for Black Americans and women. She traveled to England on lecture tours and successfully appealed to the United Kingdom for citizenship in 1865. As a Black woman in the United States she had been refused citizenship, but in Europe she found more opportunity and less blatant prejudice. Remond continued to pursue her career and education. After beginning medical training in England, she studied to become a doctor and obstetrician in Italy. She settled in Florence where she married a Sardinian businessman and spent twenty years treating patients. She died in Rome in 1894 at the age of sixty-eight.

Like Rosa Parks’s protest, the opera incident at the Howard Athenaeum was likely not a spontaneous response to racism. Instead, it was a political action designed to push for a court decision on Black rights. Despite Remond’s statement to the court that she went to the opera without “the intention of testing her rights”, her purchase of the tickets through the mail and her rapid legal response could indicate a planned protest.

Some sources indicated that she used her court winnings to fund her lecturing career. Remond was a compelling speaker who often used her status as an educated and eloquent free-born woman to appeal to Victorian sentimentality and concern for women and children’s well-being. This was the same demeanor that won her sympathy in her court case. As a “respectable colored lady”, as one contemporary newspaper called her, who was pushed unjustly from her seat at the opera, Remond could create a platform to advocate for the abolition of slavery, Black civil rights, and her own right to be heard.

Sarah Parker Remond may have been ejected from the opera, but the incident would allow her to start a career where her activism could take center stage.

Article by Jaydie Halperin, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Black Abolitionist Archive, “Sarah Parker Remond – Anti Slavery Advocate, November 1, 1860”; Boston Women’s Heritage Trail, “Sarah Parker Remond and the Howard Athaneaum”; William Lloyd Garrison, ed. The Liberator, “Rights of Colored Persons” – June 3, 1853, “The Opera Ejection Case” – June 10, 1853, “Theatrical Abuse”– September 2, 1853, “Monsieur Jullien’s Concerts” – December 16, 1853; Hamilton Hall, “Hamilton Hall and the Remond Family”; David Kruh, “Little known history behind Old Howard,” The Boston Globe; Massachusetts Historical Society, “Sarah Parker Remond.”; Mass Moments, “May 4, 1953 – Sarah Remond Ejected from Boston Theater”; National Archives, “Sarah Parker Remond’s application to become a British Citizen.”; New York Daily Times, “BOSTON.: The Convention–Liquor Law–Hoosac Tunnel–Railways–Assault at the Opera–New Hotel, &c”, 17 May 1853; Dorothy Burnett Porter, “The Remonds of Salem, Massachusetts: A Nineteenth-Century Family Revisited” Proceedings of the American Antiquarian Society, 1985; Charles Lenox Remond, “The Rights of Colored Citizens in Traveling”, 1842; Sirpa Salenius. “Transatlantic Interracial Sisterhoods: Sarah Remond, Ellen Craft, and Harriet Jacobs in England.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies 38, no. 1 (2017): 166–96.