The Yellow House at 3 Smith Court

One of the few remaining wooden structures on Beacon Hill, the long and narrow house at 3 Smith Court now stands opposite to the Museum of African American History. Over two centuries, the house has been the home to titans of the abolition movement and witnessed a constantly changing neighborhood. Homes like 3 Smith Court stand as physical reminders of the history that once took place in and around them.

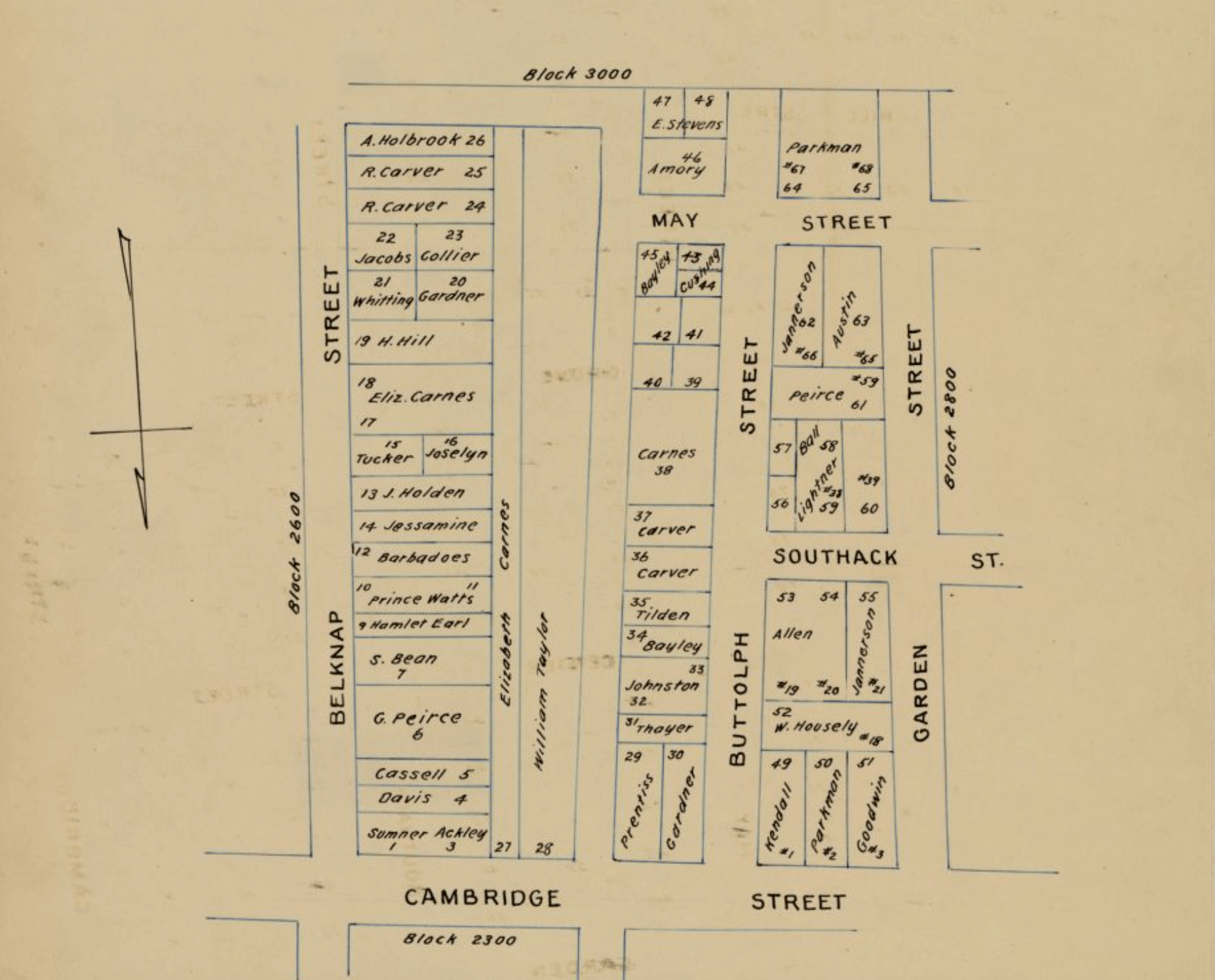

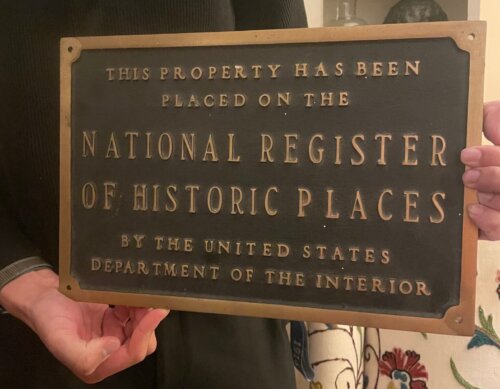

The long yellow-sided building opposite the African Meeting House on Smith Court has a storied history. Constructed between 1798 and 1800, 3 Smith Court is one of the few remaining buildings on Beacon Hill that retains some original wooden construction – although the back wall of the building is brick. Built on the footprint of a former rope walk, the Federal-style house is long and skinny with two original stories. A third story and two wing additions have been constructed over the centuries. While still privately owned today, 3 Smith Court was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1976 due to its significance to Black history and the abolition of slavery.

The original owners and builders of the house were the bricklayers William Lancaster and Benajah Brigham. They sold their interest in the property to a trader named John Powers who willed it to his wife and their unmarried daughter, Joanna, in 1826. Powers’s daughter, now married to a man named Joseph Stanford, would go on to own the house until 1865. Mrs. Stanford, however, moved away from the North Slope of Beacon Hill and began renting units of the property to Black residents.

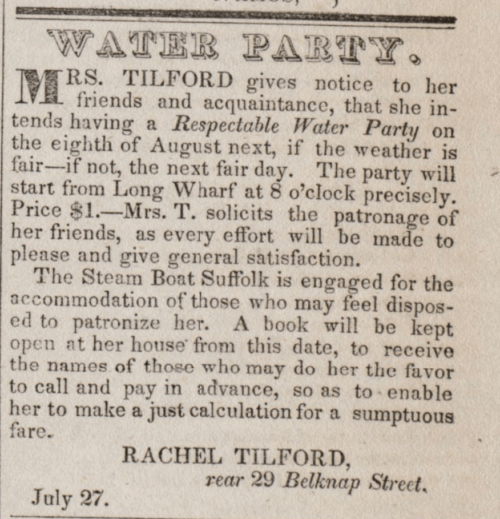

In the 1830s and 1840s, a waiter and shoe shiner named George Washington and a barber, Andrew Telford (or Tilford), lived in a subdivided 3 Smith Court. Telford and his wife, Rachel, were seemingly well-to-do, but notably not involved in the struggle against slavery. This was uncommon in the North Slope neighborhood which was the heart of the abolition movement.

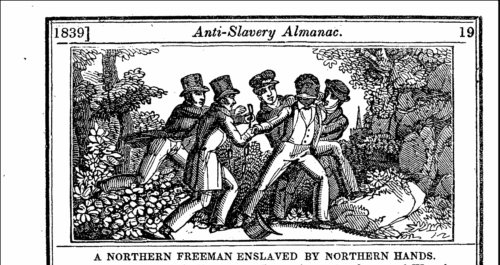

The same cannot be said about 3 Smith Court resident from 1839, James Scott. A clothes dealer, Scott assisted fugitive slaves escaping north to Canada. The Boston Vigilance Committee recorded him having sheltered the self-emancipated Henry Jackson and his family, Henry North, William West, and Robert LeRoy. The basement stairs of 3 Smith Court preserve a small piece of glass set into a hole. This allowed hidden fugitives to check who was coming down the stairs.

Scott was also among the Black Bostonians charged with helping Shadrach Minkins escape from court. Minkins, who had escaped from slavery in Virginia, had been arrested under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. At his hearing, a group of men grabbed Minkins and ushered him bodily away from the authorities who would have sent him south. Instead, Black Bostonians helped Minkins travel to Canada. Scott and two other Black clothing dealers were charged with spearheading the mob. All three were later acquitted due to lack of evidence. It is unclear if they were actually involved in freeing Minkins.

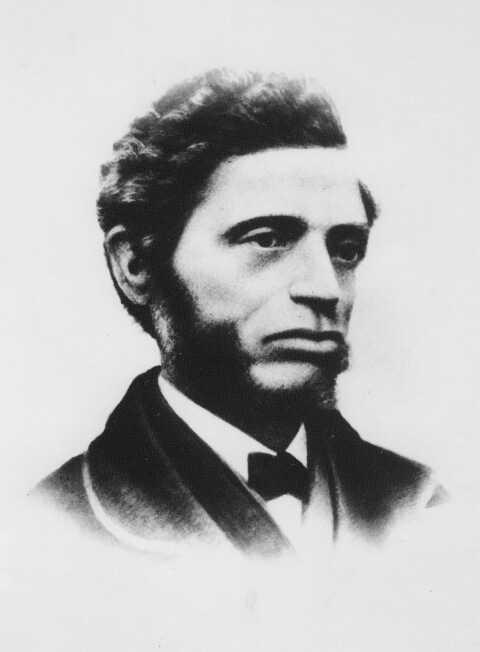

William Cooper Nell also lived at 3 Smith Court from 1850 to 1857. Nell had gone to school across the street from 3 Smith Court at the African Meeting House School. It was his experiences at the segregated school that led him to be one of the earliest activists for school integration. Nell was instrumental in the integration struggle that succeeded in desegregating Boston schools through the state legislature in 1855.

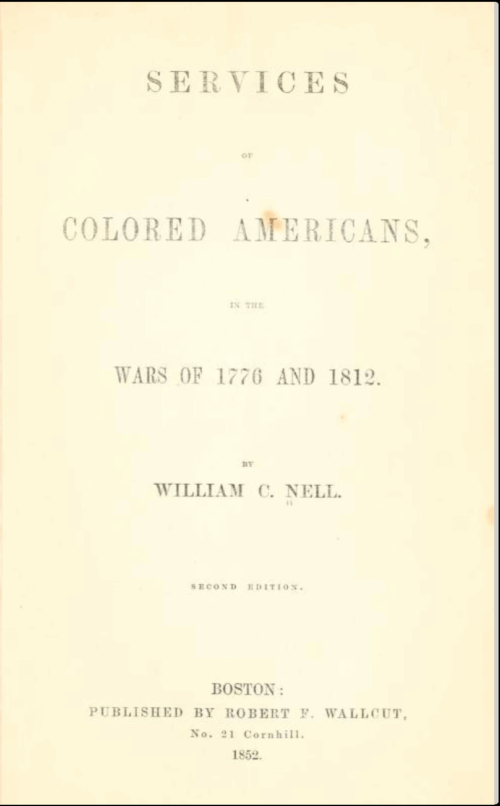

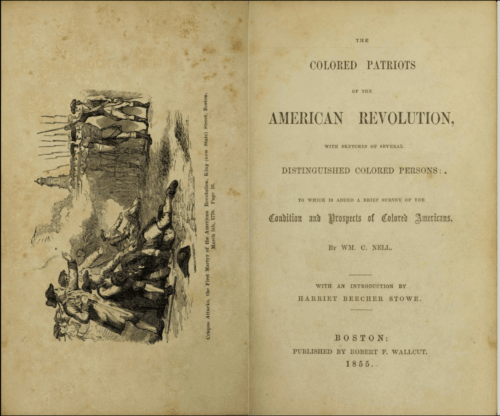

A staunch abolitionist and activist, Nell worked as an apprentice and writer for William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator for almost its entire run. He was a founder of the New England Freedom Association in 1843 which later merged with the Boston Vigilance Committee in 1850. Nell left Boston briefly to work on Frederick Douglass’s paper The North Star in 1847. When he returned he began living at 3 Smith Court. It was at this address where Nell wrote Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812 (1851) and Colored Patriots of the American Revolution (1855). This made him one of the first published African American historians. Nell continued to help fugitives escape to Canada and later became the first Black American to work for the Postal Service.

James Scott bought the property from Stanford in 1865. He owned the property until 1874 when he divided it between his son Henry and Thomas P. Taylor. Taylor later acquired the whole property when Henry Scott died before his father. In 1910, Taylor married Carolyn Washington a descendant of the shoeshine, George Washington, who used to live at 3 Smith Court. The Taylor family held the property until 1924 when they sold it to Elinor K.B. Snow.

The Snow family owned the property until 1949. The 1940 census reported her son, William B. Snow Jr. living in the house alongside several tenants. Snow conveyed the property to Margaret H. Bauer in 1949 who owned the house until her death in 1969. Bauer, who had a juris doctorate, was the first female dean of Portia Law School (later New England Law School). The 1950 census records several young women working in clerical positions living in small apartments carved out of 3 Smith Court. Bauer would have been their neighbor and landlady.

By the early 1970s, the Harvard-trained architect Mark B. Mitchell owned the house with his wife Sarah L. Mitchell. After leaving Boston, Mark went on to continue his architecture career. He became a state representative in Vermont in 2006. Sarah was a tenured professor at Vermont College for 25 years where she led the Masters in Education program.

The current owners have kept their home at 3 Smith Court in as unchanged a condition as they could. It was under their stewardship that the house was designated a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. Today, the house maintains a historic charm with handmade tiles and plaster walls that are not quite level.

Today, visitors to the Museum of African American History, which occupies the Abiel Smith School and African Meeting House, can see 3 Smith Court when looking out of the sanctuary window. This wooden clad house with its shuttered windows and narrow garden has remained almost unchanged for over 200 years. Visitors share the same view as the titans of the abolitionist movement who once looked out on the house. The house at 3 Smith Court has been lived in and witnessed by many of history’s change makers. Thanks to those who have preserved it through the decades, a relic of that history remains visible through that same window.

Article by Jaydie Halperin, edited by Bob Potenza

Special Thanks to Suzanne Berger Keniston and Katherine Dander

Sources: Boston Globe September 5, 1938, May 28, 1960, February 17, 1965, January 5, 1968, October 7, 1974; Holly K. Chamberlain “Historic American Buildings Survey: William C. Nell House” (National Parks Service, June 25 1987); Family Search, “Margaret H. Bauer” 1950 United States Census; Kathryn Grover and Janine V. da Silva, “Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site,” (National Park Service, December 31, 2002); Keith N. Morgan, “Smith Court”, (Society of Architectural Historians); National Archives Catalog “1940 Census Population Schedules – Massachusetts – Suffolk County – ED 15-156”; National Parks Service, “Smith Court Residences,” (December 13, 2024) | “Smith Court Stories” | “William Cooper Nell” (January 16, 2025); New England Law School, “Our History”; Adam Tomasi, “William Cooper Nell” (The West End Museum, November 16, 2021); The White River Valley Herald, “Mark B. Mitchell- Obituary” (November 10, 2011); Valley News “Sarah L. Mitchell- Obituary” (May 25, 2016).