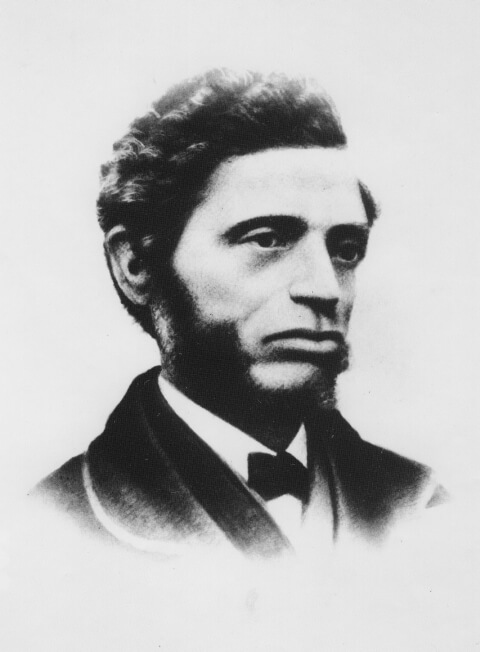

William Cooper Nell

William Cooper Nell, the United States’ first Black historian, was an intellectual and abolitionist who became an integral part of The Liberator’s staff and advocate for Black rights. He was also the first Black person to serve in the federal civil service, and was deeply involved in desegregating Boston schools.

William Cooper Nell was born on December 20, 1816 to William Guion Nell and Louisa Marshall, free African Americans who lived on 64 Kendall Street on the north slope of Beacon Hill. William Cooper’s father was originally from the free black community of Charleston, South Carolina, as an apprentice to tailor and hotel owner Jehu Jones. He left Charleston during the War of 1812 and ended up in Boston, marrying Marshall, a resident of Brookline, in 1816. At twelve-years-old, William Cooper Nell attended the African Meeting-House School. He won the Franklin Medal, an academic prize awarded to children from Boston’s public schools who performed exceptionally on a city-wide exam. But the city denied Nell and two of his classmates the right to attend the awards banquet, because of their race. Nell got hired as a waiter for the event simply so he could be let in, but this was an indignity. Nell recalled about the event, “the impression made upon my mind by this day’s experience deepened into a solemn vow, that, God helping me, I would do my best to hasten the day when the color of the skin would be no barrier to equal school rights.”

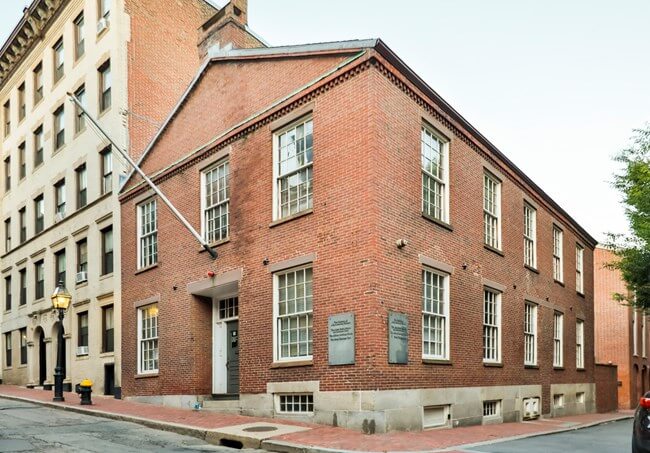

In 1844 and 1845, Nell and other black Bostonians petitioned the city to abolish segregated schools, but the Primary School Committee voted to maintain inequality. However, Nell became instrumental to a mass movement that eventually compelled the state legislature, and Governor Henry Gardner, to abolish school segregation in 1855 — making Boston the first large US city to integrate public schools — and close the segregated Abiel Smith School that had succeeded the African Meeting-House School.

Nell’s lifelong dedication to organizing and publishing was multifaceted. He studied law under abolitionist William Bowditch, and considered becoming an attorney; but Nell ultimately refused, because admission into the bar required an oath to defend the Constitution, which at that time had a clause requiring that states capture and return fugitive slaves. He proceeded to found the New England Freedom Association in 1843, which joined forces with the Vigilance Committee in 1850, after the Fugitive Slave Act passed Congress. The Vigilance Committee led the grassroots attempt to free Anthony Burns, a fugitive slave in Boston robbed of his freedom by the courts.

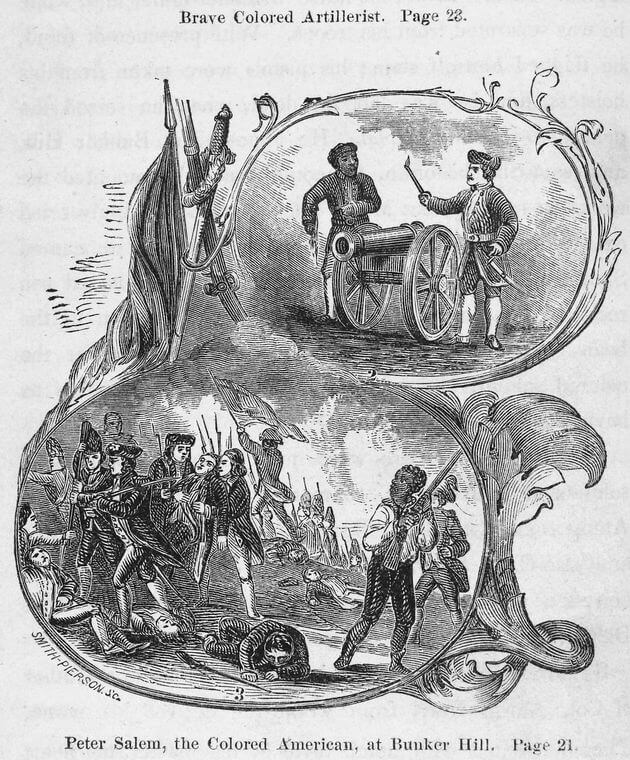

Nell frequently wrote for William Lloyd Garrison’s The Liberator, briefly edited Fredrick Douglass’ oft-renamed paper in Rochester, NY, and became a historian. He wrote Services of Colored Americans in the Wars of 1776 and 1812 in 1851, which, in Nell’s words, was intended to spotlight African Americans’ “patriotism and bravery” exhibited in a “much-neglected department of American history.” In 1861, Nell was nominated by Boston’s federal Postmaster, John Palfrey, for a clerk position, which made Nell the first Black person to serve in the federal civil service. Nell remained a writer, reporting for New York’s Weekly Anglo-African on the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the first all-black volunteer regiment of the Union Army, in 1863. He observed the 54th’s march through Boston and connected their service to Crispus Attucks, a free black man slain in the Boston Massacre, making him the first person of any race to die for American independence. Watching the free black soldiers, Nell wrote of his imagination of “the free, the happy future, as within a seeming hailing distance.”

Nell died from a stroke in 1874. The essential focus of his life was to advance the freedom and equality of African Americans, both free and enslaved, in a city known today as the “cradle of liberty.”

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Source: The Bay State Banner; Historians Against Slavery; Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889 (New York: Penguin Press, 2012)