The Frances E. Willard Settlement House

Founded in 1894, the Frances E. Willard Settlement House was located on the West End’s Chambers Street for nearly five decades. The Settlement House aimed to serve the neighborhood’s immigrant population and factory workers by offering social services, community clubs, and housing to young women and children.

From the 1880s to the 1920s, hundreds of settlement houses were founded across the United States. Responding to quickly growing immigrant populations and rapid industrialization, settlement houses were established to provide a broad range of social, health, and educational services to immigrants and the urban poor. These community centers were influential institutions in Boston and its West End, which had a number of settlement houses, like the Elizabeth Peabody House, the West End House, and the Frances E. Willard Settlement House on Chambers Street.

The Willard Settlement was founded by Caroline Matilda “Tillie” Caswell (1864-1938) in 1894. A native of Charlestown, Caswell had attended a convention of social workers in Baltimore, and was so inspired by a speech by Frances Willard – founder of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) – that she returned to Boston determined to set up a settlement house in Willard’s honor. Caswell initially opened the settlement in three rooms of a tenement house at 422 Hanover Street, catering primarily to women who worked at local factories.

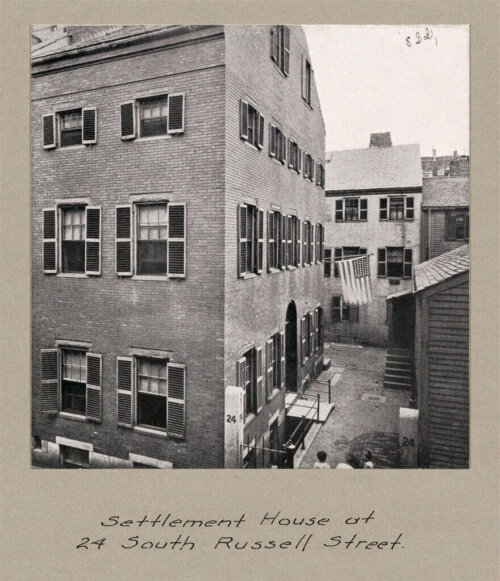

Caswell’s settlement was popular and quickly expanded. The Willard Settlement opened a coffee bar and free lunch station at the Hanover tenement in 1895; opened a Young Woman’s Home at 11 Myrtle Street in 1897; rented a beach house for working girls’ vacations in 1899; moved the settlement into two houses at 24 South Russell Street in 1901; and opened a playground on South Russell Street in 1902. The Frances E. Willard Settlement was officially incorporated July 7, 1903, and purchased the property of 38-46 Chambers Street in the West End in 1907.

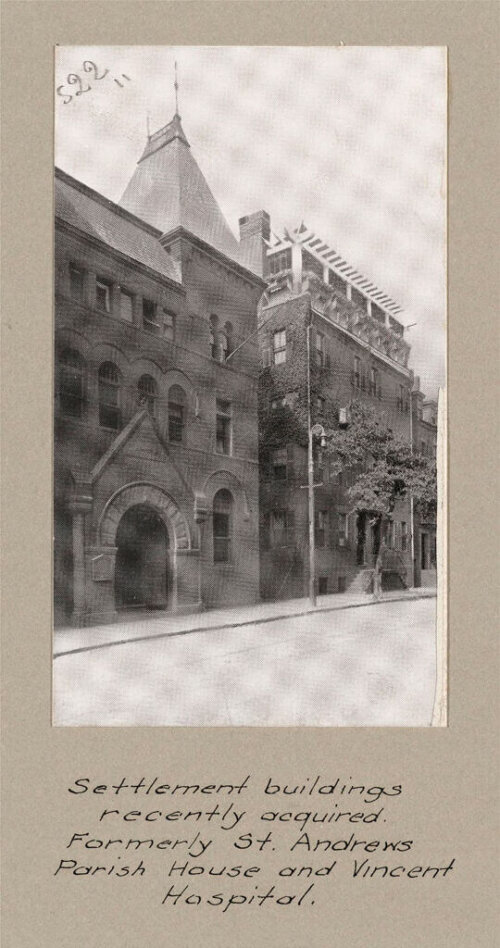

The Frances E. Willard Settlement on Chambers Street operated within the converted buildings of Vincent Memorial Hospital and St. Andrew’s Church, and included a Club House (38 Chambers St.), the Phillips Brooks Hall (40-42 Chambers St.), and the Frances E. Willard House (44-46 Chambers St.). According to a 1910 promotional pamphlet, the Settlement’s mission was:

Providing, maintaining and supporting a home or homes for young working women or women earning very low salaries or those training for self-support who need temporary aid, and helping in any possible way those who are strangers and need assistance; also establishing, maintaining and supporting a settlement for the social, educational and moral enlightenment and training of those with whom it comes in contact.

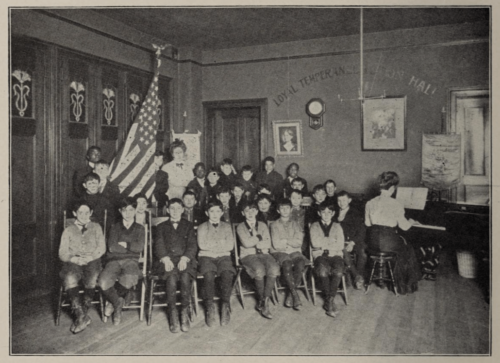

The House at 44-46 Chambers contained 40 rooms, which were able to accommodate 27 young women, 8 resident settlement workers, and 3 “transients.” It had a reception room and parlor for welcoming callers; a sitting room for sewing and reading; a roof deck, which girls often slept on in the summer; and a dining room, for “family” meals and mandatory daily prayers. The Willard House, affiliated with the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, adhered to Christian and Temperance principles. Rooms were reserved for girls of “good moral character earning low wages or training for self-support on a very small income.”

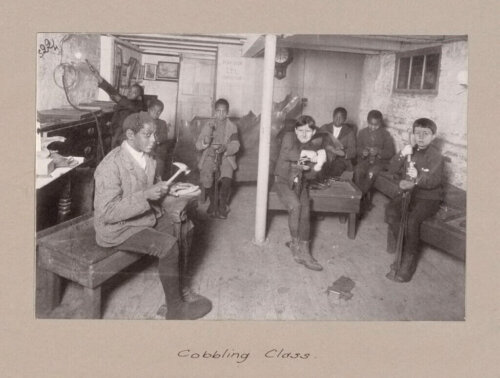

The Willard’s clubhouse next door had an auditorium, gymnasium, library, pharmacy, assembly hall, and craft room. Here, 990 young women, girls, and boys of “various nationalities” attended the 80 clubs and classes on offer, from folk dancing, to gymnastics, to basketball. Some of the most popular clubs included the Boy Cobblers, which met twice weekly to repair their own or their family’s shoes; the Loyal Temperance Legions, whose 470 children members signed a threefold pledge against liquor, tobacco, and profanity; the housekeepers classes for girls; the St. Andrew’s Girls’ Industrial Club, which taught dressmaking, embroidery, and stenography; the Merrimac Young Men’s Club, which focused on the development of body, mind, and character; and the Elocution Club, where girls learned lessons in patriotism and loyalty. Moral education was also provided daily on “truth, cleanliness, helpfulness, kindness, love, courtesy, courage, honor and the golden rule.”

Willard Settlement, like other settlement houses, was not solely altruistic, but a force for propagating Christianity, Temperance, and Americanization, particularly through classes on patriotism and twice-weekly English classes for immigrant mothers. When a boy at the Willard Settlement was asked to summarize what the organization was, he replied: “It is a place where the children are taught how to do many useful things, as sewing, carpentering, making baskets, etc., and are also taught the most important thing of all, to have a pure soul.”

Willard Settlement continued to expand, purchasing property for the Llewsac Lodge Rest Home and Industrial Center in Bedford in 1909. Llewsac (“Caswell” spelled backwards) was a complex designed as a residential home for older women and a vacation spot for factory girls living at the West End settlement house. The Bedford property contained a 185 acre working farm, orchards, a 20-room house, a laundry building, a gardener’s house, and a barn.

Caswell served as the head of the Settlement for 37 years. Successive presidents, including Agnes Welch, continued Caswell’s mission on Chambers Street. The Chambers Street property was sold in 1955, and destroyed a few years later under urban renewal. However, Caswell’s work and legacy still survive today in Bedford: In 1975, Frances E. Willard Homes and the Elizabeth Carleton House merged, and after years of construction, opened the Carleton-Willard Village in 1982, on the site of Willard Homes’ original Llewsac Lodge. Carleton-Willard Villages continues to care for elderly adults in Bedford, carrying on Caswell’s devotion to caring for others that began in three rooms of a tenement building, and thrived for decades on the West End’s Chambers Street.

Article by Grace Clipson, edited by Bob Potenza.

Sources: The Boston Globe, “Agnes Welch, 89; active in clubs, widow of lawyer in famed hearings,” December 1, 1985; Carleton-Willard Village, “Vision, Commitment And Care: Celebrating 125 Years Of Service,” Village Insights (2009); Carleton-Willard Village, “What’s In A Name?,” The Carleton-Willard Villager (2020); Beverly Koerin, “The Settlement House Tradition: Current Trends and Future Concerns,” The Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare 30 (2003); Susan Martin, “The Frances E. Willard Settlement in Boston,” Massachusetts Historical Society (2023); Massachusetts Historical Society, “Hill Family Papers”; The New York Times, “Caroline M. Caswell, Boston Sociologist,” December 19, 1938; Simmons University Archives, Frances E. Willard Settlement Informational Pamphlet (1910); Suzanne M. Spencer-Wood and Renée M. Blackburn, “The Creation of the American Playground Movement by Reform Women, 1885–1930: A Feminist Analysis of Materialized Ideological Transformations in Gender Identities and Power Dynamics,” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 21, no. 4 (2017): 937–977; Katharine Lent Stevenson, “Massachusetts,” in Organization and Accomplishments of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union in Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, North Dakota, Ohio, and Virginia (1908); West End Project Appraisal Report, Chambers Street 38-46 (The West End Museum Archives).