West End Women: A Self-Guided Walking Tour

Below is an online, self-guided version of our “West End Women” walking tour. Print it out or keep it digital, and put on your best walking shoes to explore the histories and stories of women from Boston’s West End.

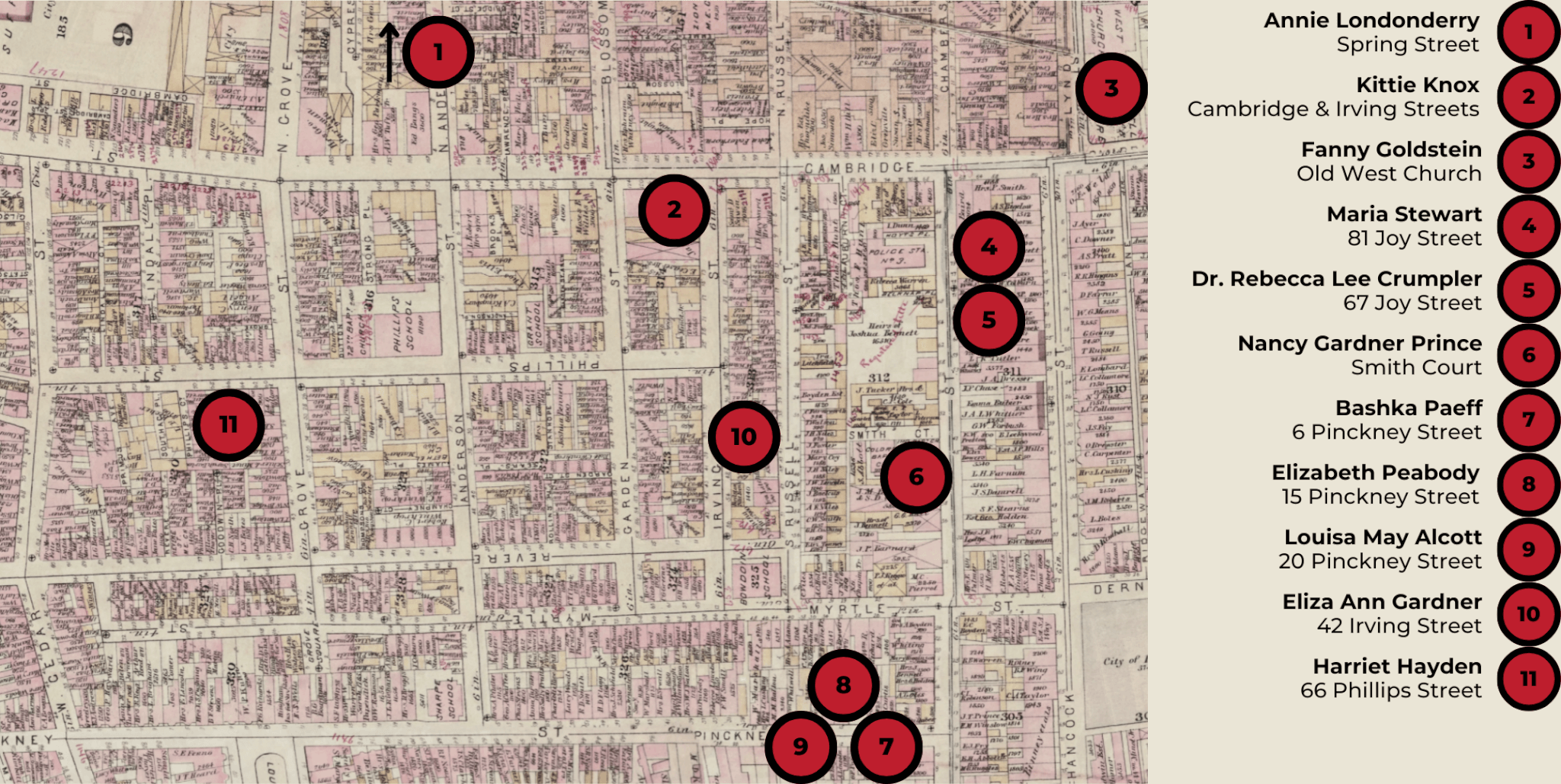

This self-guided walking tour focuses on the stories of 11 remarkable women – athletes, authors, artists, abolitionists, and activists – who called the West End home. Begin your tour at The West End Museum and walk through Thoreau Path and up the North Slope of Beacon Hill. These women’s lives span from 1799 to 1979.

Before we begin, you may be wondering: why does this “West End” tour go into Beacon Hill? The Historic West End (or pre-Urban-Renewal West End) extended up the North Slope all the way to Pinckney Street! While this section today belongs to the Beacon Hill neighborhood, the women we talk about on this tour, during their lifetimes, would have been living in the Historic West End. More information about the changing borders of the West End can be found HERE.

Stop 1: Annie Londonderry

Location: Spring Street (no longer exists; near Thoreau Path today)

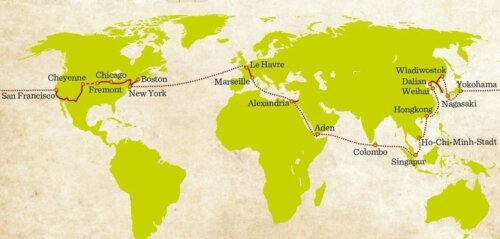

Annie Cohen Kopchovsky, also known as Annie Londonderry, was born in Latvia in 1870 to Jewish parents and emigrated to the West End with her family in 1875. Her famous bicycling adventure began with a bet, as legend tells it. In 1894, a gentleman in Boston bet another gentleman that no woman could travel around the world on a bike. This accomplishment had been completed for the first time by a man less than a decade prior. Annie Cohen Kopchovsky took on the bet and set out from Boston on June 25, 1894, at age 23, to attempt the journey (see map above). Along her way, crowds gathered at her every stop to hear tales of her adventures, and reporters eagerly shared her progress. Upon the completion of her travels in 1895, she became the first woman to bicycle around the world.

Full article HERE.

Stop 2: Kittie Knox

Location: Corner of Cambridge and Irving Streets

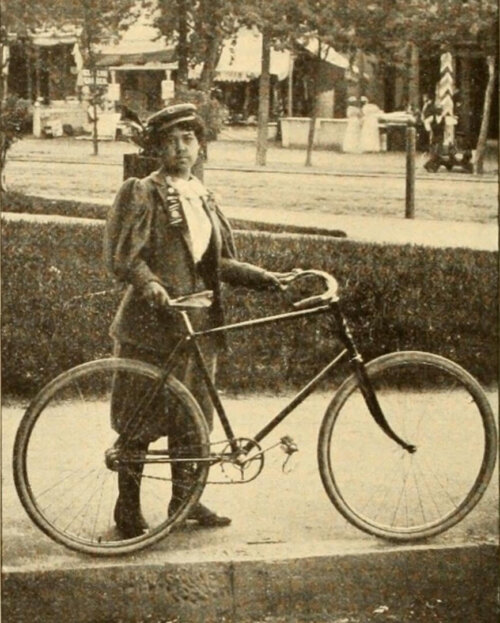

Katherine “Kittie” Knox was born to a white mother and Black father in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1874, and moved with her mother and brother to the corner of Cambridge and Irving Streets in the West End in the early 1880s. The young Knox worked as a dressmaker and seamstress, but her passion from a young age was cycling. In 1893, Knox was a founding member of the Riverside Cycling Club in Cambridge, a Black cycling group, and that same year was accepted as a member of the League of American Wheelmen (L.A.W). The following year, the L.A.W. changed its constitution to include a “white only” membership clause, but this didn’t stop Knox. She competed in the L.A.W.’s national competition in 1895, despite being barred from hotels due to her race. Arguments ensued between members of the L.A.W. who wanted to uphold the white-only rule, and those who wanted to desegregate. In 1895, the L.A.W. released a statement declaring that, because Knox joined before the constitution change, it could not be retroactively applied to her. After this ruling, Kox was accepted as a full member, officially becoming the first African American to be accepted by the League of American Wheelmen. Unfortunately, her career was short-lived: Knox died of kidney disease in 1900 at Mass General Hospital, at the age of 26.

Full article HERE.

Stop 3: Fanny Goldstein

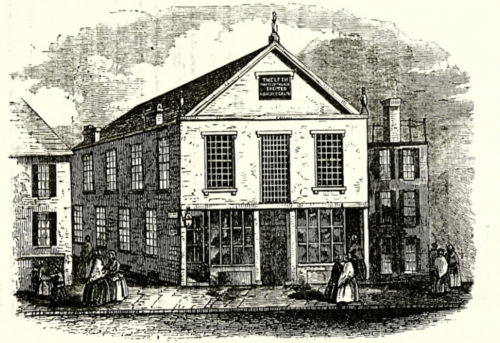

Location: Old West Church, Cambridge Street

Fanny Goldstein (1895-1961), an immigrant from the Russian Empire (present-day Ukraine), became the first Jewish head librarian of any library in Massachusetts in 1922, at the West End Branch. The branch, since its founding in 1896, was located in the Old West Church. One of Goldstein’s primary goals as a librarian was to celebrate the diversity of the West End’s racial, ethnic, and religious communities. As part of this, she founded Jewish Book Week in 1925, and held book weeks for other racial and religious groups as well, such as Catholic Book Week and a Black History Week. Goldstein announced her retirement at the West End Branch’s annual interfaith Christmas-Hanukkah party in 1957. The Boston Globe reported the next day that “the West End changed a little last night.”

Full article HERE.

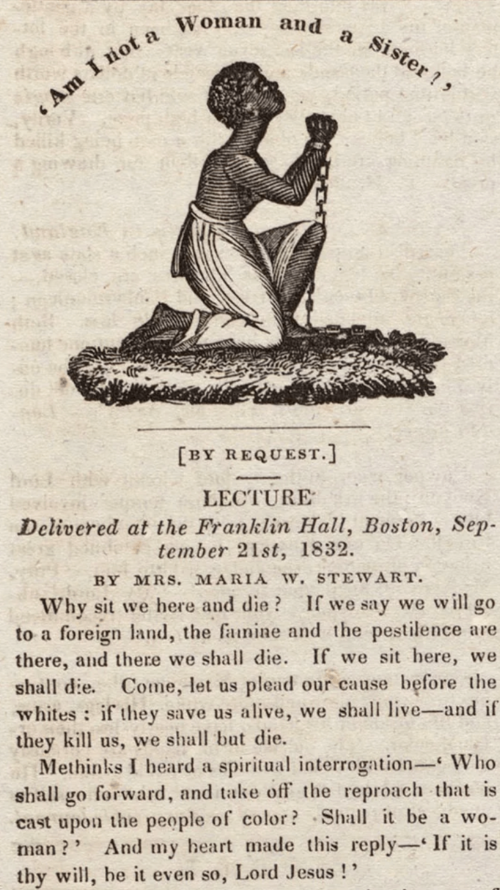

Stop 4: Maria Stewart

Location: 81 Joy Street

Maria Stewart was a Black woman born free in Connecticut in 1803. Orphaned at five years of age, she became an indentured servant to a minister, and taught herself to read and write by sneaking books from his library. In the 1820s, she married and moved to Joy Street, where she also attended church services at the African Meeting House. Here, she became active in the abolitionist movement, and William Lloyd Garrison – impressed by her intellect – published many of her writings in The Liberator. Her pamphlets helped to launch her into a public speaking career, and, in September 1832, Stewart spoke to an audience of men and women at Franklin Hall, meeting place of the New England Anti-Slavery Society. This speech was one of the first recorded cases of any American woman, Black or white, speaking to a public audience. In her speeches to mixed-race and mixed-gender audiences, Stewart addressed both domestic and global political issues. Her speaking and writing influenced other prominent activists and abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth.

Full article HERE.

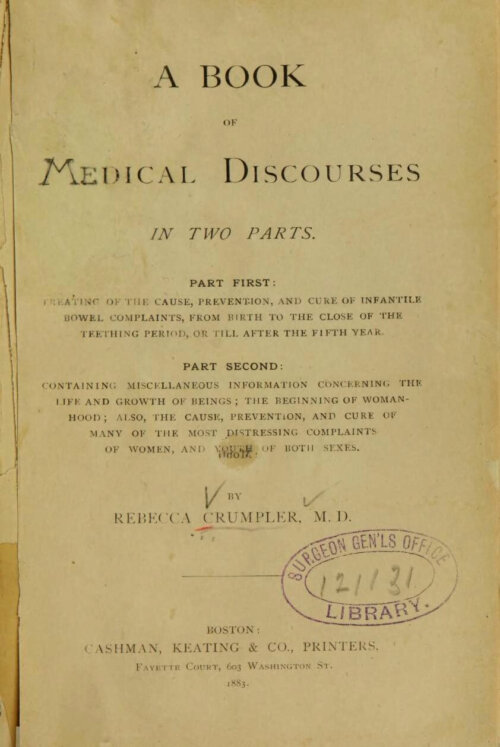

Stop 5: Dr. Rebecca Lee Crumpler

Location: 67 Joy Street

Upon Rebecca Lee Crumpler’s (1831-1895) graduation from the New England Female Medical College in 1864, she became the first Black woman in the United States to earn an M.D. Dr. Crumpler moved south to Virginia after the Civil War to care for formerly enslaved people. Afterwards, she returned to Boston and lived on Joy Street, where she treated patients regardless of their ability to pay.

Full article HERE.

Stop 6: Nancy Gardner Prince

Location: Smith Court: African Meeting House & Abiel Smith School

Nancy Gardner Prince was a Black woman born in 1799 in Newburyport, Massachusetts. At the age of 15, she moved to the North Slope of Beacon Hill in the West End. Here, she was baptized by the influential minister and abolitionist Reverend Thomas Paul at the African Meeting House. In 1823, she met Nero Prince and married him the following year. Nero was a Black man who, prior to arriving in Boston, had signed on with a merchant seaman and visited Russia several times. A Russian noblewoman hired him as a servant and later he was given a role on the staff of the Tsar in St. Petersburg. This was why Nero returned to Russia in 1824, bringing his new wife, Nancy, with him. While in St. Petersburg, Nancy learned the language, started a business making and selling children’s clothing, boarded children, and eventually established an orphanage. After nearly a decade in Russia, Nancy returned to Boston in 1833 due to ill health. While Nero planned to follow her, he died in Russia before he was able to. Upon returning to Boston, she: established a society for orphans; became a founding member of the New England Non-Resistance Society; became a member of the Boston Female Anti-Slavery Society; and held a series of lectures on Russian culture at the Abiel Smith School and the AME Zion Church. In her later years, she spoke at the 1854 Women’s Rights Convention in Philadelphia and published a book, A Narrative of the Life and Travels of Mrs. Nancy Prince Written by Herself. The book is significant as a rare travelog of a Black woman in the pre-Civil-War era; it is also noteworthy in the study of Russian history, given Nancy’s eyewitness accounts of the political upheaval of the St. Petersburg riots after the unexpected death of Alexander I in 1826.

Full article HERE.

Stop 7: Bashka Paeff

Location: 6 Pinckney Street

Sculptor Bashka Paeff was born into a Jewish family in Minsk (then part of the Russian Empire) in 1893, and immigrated with them to Boston when she was one. After a brief stint in the North End, the family settled on 6 Pinckney Street, where Paeff would eventually set up her artist’s studio. She attended the Massachusetts Normal School (today’s Massachusetts College of Art), where she studied with Cyrus Dallin. Paeff worked her way through school, partly as a ticket seller in the Park Street T Station. Here, she became known as the “subway sculptor,” as she often worked in clay during her shift. By the age of 23, Bashka had become an important figure in the Boston arts community, and won commissions to create busts of prominent figures, such as Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and sociologist Jane Addams. Come back to The West End Museum after you finish the tour to see some of her sculptures in our permanent exhibit!

Full article HERE.

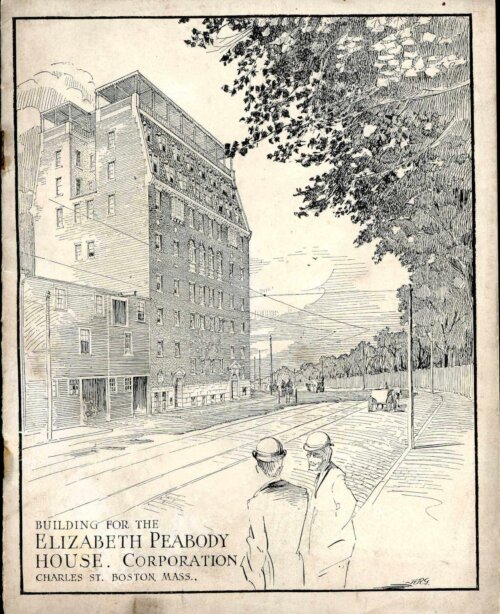

Stop 8: Elizabeth Peabody

Location: 15 Pinckney Street

In 1860, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody (1804-1894) opened the first English-speaking kindergarten in the U.S. at 15 Pinckney Street. Peabody was inspired by her experience with a German-speaking kindergarten in Wisconsin and by the teachings of Friedrich Fröbel, a German pedagogue who coined the term “kindergarten.” Elizabeth’s kindergarten here at Pinckney Street included areas for singing, playing, music, and movement. The furniture was to be moveable and the space able to be manipulated; and ideally, as Peabody wrote, the entire room should be built at a child’s scale. In 1867, Peabody traveled to Europe to tour kindergartens and to further research Fröbel’s teachings. She returned a strong advocate for free early childhood education in American cities. Peabody died at 89 in January 1894, but the Elizabeth Peabody House continued her important work in educating children. The organization was primarily a settlement house for the West End’s immigrant families, and in 1912 relocated to a new seven-story building on Charles Street, with a library, gym, kindergarten, and community theater.

Full article HERE.

Stop 9: Louisa May Alcott

Location: 20 Pinckney Street

While Author Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888) is best known for her book Little Women, based on her upbringing in Concord, Massachusetts, she also lived in multiple homes in Boston throughout her life. At first while living in Boston, Alcott sewed, taught, and worked as a governess, sending much of her money back home to her family in Concord. In 1852, however, the Alcotts moved to 20 Pinckney Street, after selling their Concord home. Louisa, aged 19, lived on the third floor of the Pinckney Street home. It was while living here that Alcott’s first work of fiction was published: “The Rival Painters: a Tale of Rome.” Of it, she wrote in her journal: “My first story was printed, and $5 paid for it. It was written in Concord when I was sixteen. Great rubbish! Read it aloud to sisters, and when they praised it, not knowing the author, I proudly announced her name.”

Stop 10: Eliza Ann Gardner

Location: 42 Irving Street

Born in New York in 1831, Eliza Gardner moved with her family to the West End at a young age and attended the Abiel Smith School. Her family lived on North Grove Street and later North Anderson Street in the West End – the latter house became a stop on the Underground Railroad where young Eliza became acquainted with abolitionist leaders, including William Lloyd Garrison, Lewis and Harriet Hayden, Frederick Douglass, and Harriet Tubman. Gardner grew up actively involved in the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church in the West End, which was on North Russell Street from 1866 to 1902. At the age of 27, Gardner organized a successful fundraising campaign for her church, but when she tried to take on other leadership roles, she was denied because she was a woman. This inspired Gardner and other women in her congregation to fight to change church law. Based in large part on Gardner’s efforts, in 1876 women won the right to vote and hold office in the AME Zion Church, and by the 1880s, women were able to be licensed preachers and officers in AME missionary societies. Outside the church, Gardner was involved in movements for abolition, human rights, women’s rights, and temperance. She was a founding member of the Boston-based Black women’s club, the Woman’s Era Club, and helped organize the first National Conference for Colored Women in America in 1895, working alongside Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Maria Baldwin, Florida Ridley, and others. In her 70s, she purchased 42 Irving Street, where she continued her work, remained a popular public speaker, and at the age of 87, published a history of her church, A Historical Sketch of the A.M.E. Zion Church in Boston.

Full article HERE.

Stop 11: Harriet Bell Hayden

Location: 66 Phillips (formerly Southac) Street

In 1844, Harriet Bell Hayden (c. 1816–1893), along with her husband, Lewis, and son, Joseph, escaped slavery in Lexington, Kentucky. They settled on the North Slope at 66 Phillips Street, turning their home into a safe house stop along the Underground Railroad. The family helped hundreds of self-emancipated Black people on their journey to freedom, particularly in the wake of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. They also attended the Church of the Fugitive Slave, another important abolitionist hub, a block away from their home. Harriet spent more than a decade sheltering freedom seekers in the family home. While Lewis tended to his clothing store on Cambridge Street, Harriet handled the day-to-day operations of the boarding house, and provided food, shelter, and protection to freedom seekers, like William and Ellen Craft. The Haydens also used their home as a meeting space, hosting prominent abolitionists visiting the city. In 1859, John Brown stayed with the Hayden family while preparing for the famous raid on Harpers Ferry, Virginia that same year. Harriet also supported various other causes, such as Boston temperance groups and the West End Woman Suffrage League. When she passed away in her home in 1893, Harriet left $5,000 to Harvard University to create a scholarship for Black students pursuing a career in medicine.

Full article HERE.