The Greatest Political Enemies of the 20th Century: West End's Lomasney Vs. Mayor Curley

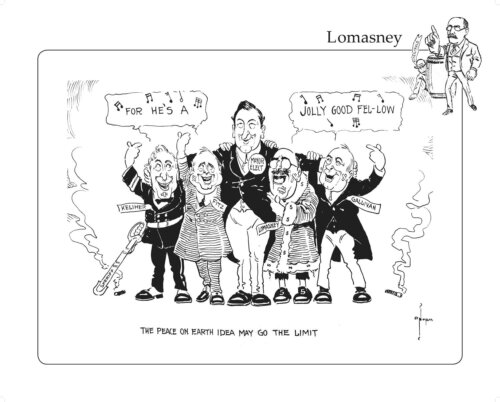

In the early decades of the 20th century, two towering figures dominated Boston’s political landscape. Their rivalry was so bitter that it reshaped the very nature of urban Democratic politics. The feud between Martin Lomasney, the “Mahatma” of the West End, and James Michael Curley, the flamboyant four-time mayor, represented personal animosity and a clash between old-style ward politics and the age of citywide political celebrity.

The Combatants: Two Sides of Irish Boston

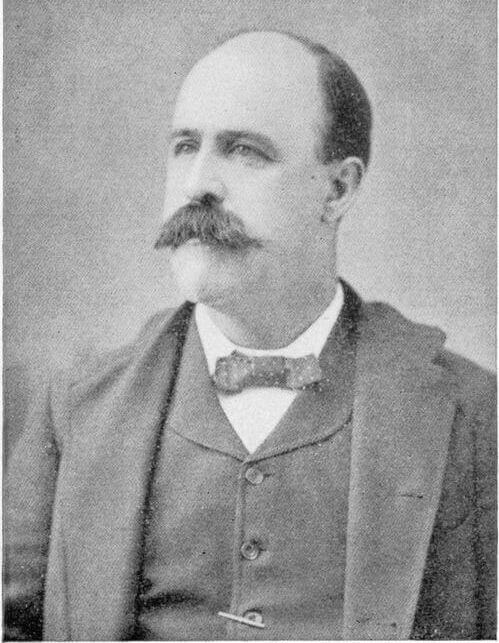

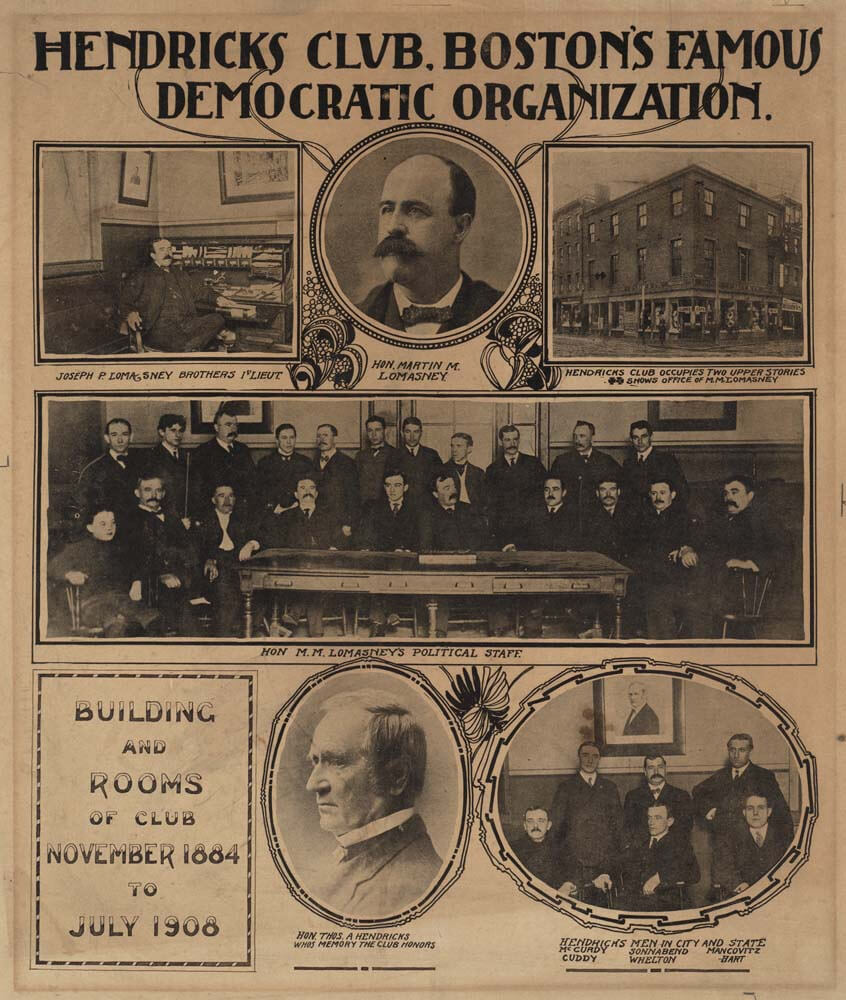

Martin Lomasney (1859-1933), dubbed “The Mahatma” and “The Czar,” ruled Boston’s West End Ward 8 (later Ward 5, then Ward 3) with mathematical precision. His domain encompassed a diverse constituency of “4,800 ‘Americans,’ 7,200 Irish, 1,100 Italians and 6,300 Jews.” From his headquarters at the Hendricks Club, Lomasney operated what many considered the most efficient political machine in the city. Personal relationships, daily accessibility, and systematic patronage placed allies in positions from health inspectors to city commissioners.

James Michael Curley (1874-1958) represented the new breed of politician. He was theatrical, ambitious, and unbound by traditional ward loyalties. The son of Irish immigrants from Roxbury, Curley served jail time for taking a civil service exam for a friend. His first incarceration was 60 days at the Charles Street Jail in the West End (now the Liberty Hotel), right in Lomasney’s territory. Curley transformed this scandal into political gold with the slogan “He Did It For a Friend.” Unlike Lomasney’s methodical approach, Curley pursued broader political ambitions that transcended neighborhood boundaries. He sought to become a citywide and eventually statewide political force.

The Setting: Boston’s West End

The battlefield for their conflict was Boston’s West End, a dense neighborhood that embodied the transformation of American cities in the early 1900s. As mentioned in one of Curley’s biographies, Lomasney’s territory was cramped. The place “where so many immigrants of all kinds got their foothold in the New World, had 173.6 people per acre.” This diverse enclave housed successive waves of immigrants in tenements and boarding houses. This created a complex social fabric that required delicate political management. Lomasney understood that effective ward politics meant personal service to each constituent. Irish dockworkers, Jewish merchants, Italian laborers, and established Americans alike found their way to the Hendricks Club seeking jobs, legal help, or advocacy.

The West End’s residents lived in a world where political loyalty was both practical necessity and social currency. Ward bosses like Lomasney solicited votes by providing essential services in an era before government social programs. A word from “The Mahatma” could mean the difference between employment and destitution, between navigating city bureaucracy or being lost in red tape.

The Evolution of Enmity

The Lomasney-Curley feud began around 1900 when Curley entered Roxbury politics, though they initially operated in different spheres with little contact. Their first major clash came in 1912 during the gubernatorial primary. Each backed opposing candidates. This political conflict would define Boston Democratic politics for decades.

Lomasney supported Curley for mayor in 1914 against the reform-minded Good Government Association’s candidate. However, their alliance soured when Curley allegedly attempted to expand Ward 8’s boundaries to gain more voters and “destroy the Lomasney machine.” This betrayal cut deep for Lomasney, who valued loyalty above all political virtues. The relationship deteriorated completely in 1917 as Lomasney felt betrayed over ward redistricting. He decided to “beat Curley for not coming to his aid in the matter of the ward lines” and threw his support behind Republican Andrew J. Peters. He even resigned as Schoolhouse Commissioner to signal his complete opposition to Curley’s re-election.

Personal Warfare and Political Tactics

What made their conflict particularly bitter was how personal it became. Curley publicly attacked Lomasney, threatening to “drive him out of the city.” The usually controlled Lomasney began referring to Curley as his “greatest political enemy.” This was an extraordinary admission from a man who had battled countless political rivals over three decades. Curley himself recalled the epithet in his autobiography. The hostility escalated to the federal level when Lomasney used his influence in the U.S. House of Representatives to demand that reports on Curley’s finances as mayor be submitted to the Attorney General “for appropriate action.”

The two men employed vastly different political styles. Lomasney operated through careful cultivation of personal relationships and behind-the-scenes maneuvering. Curley, by contrast, was a master of public spectacle and rhetorical flourish. He could, as one contemporary noted, “use a different side of his mouth for either side of Beacon Hill.” He charmed Back Bay Brahmins with cultured eloquence, then crossed the city to deliver “spirited, rabble-rousing” speeches that could “practically incite whole national groups to riot.”

The Broader Historical Significance

Their feud represented a fundamental transformation in American urban politics. Lomasney embodied the traditional ward boss system—neighborhood-based, relationship-driven, and built on personal loyalty. Curley represented the future: media-savvy, personality-driven citywide politics that relied more on public appeal than private obligation. This conflict also reflected different models of immigrant political integration. Lomasney’s approach emphasized working within existing systems, building careful coalitions, and maintaining stability. Curley’s method involved challenging established order, appealing to ethnic pride and grievances, and using controversy to build name recognition.

The Reconciliation

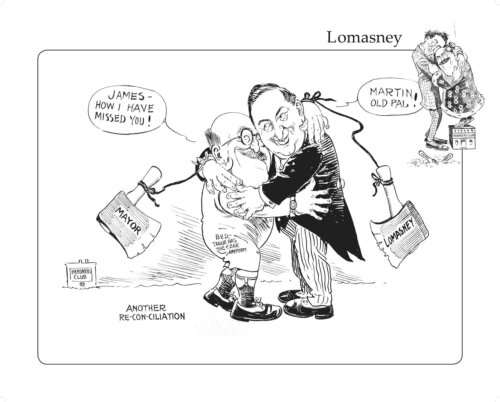

By 1929, both aging politicians recognized the futility of their twelve-year war. In a remarkable about-face, Lomasney endorsed Curley for mayor against Frederick W. Mansfield. He spoke for “an hour and a half” at the Hendricks Club and urged members to vote “for Mr. Curley, with no ifs, ands, or buts.” This reconciliation came too late to restore Democratic unity in Boston. The prolonged warfare had fractured the party and allowed Republican victories.

Legacy of the Feud

The Lomasney-Curley conflict symbolized the twilight of the ward boss era and the rise of the modern political celebrity. Curley’s approach—flamboyant, controversial, and personality-driven—would become the template for 20th-century urban politics. Lomasney’s methodical machine-building represented a dying art. Their rivalry also demonstrated how personal animosity could reshape entire political systems. What began as a disagreement over ward boundaries evolved into a fundamental battle over the future of Democratic politics in Boston. The consequences extended far beyond the West End’s diverse streets to influence the trajectory of American urban governance for generations to come.

Article by Amir Tadmor, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Leslie G. Ainley, Boston Mahatma: The Public Career of Martin M. Lomasney,(Boston: Bruce Humphries, Inc., 1949); Jack Beatty, The Rascal King: The Life and Times of James Michael Curley (1874-1958), (Boston: Da Capo Press, 1992); James Michael Curley, I’d Do It Again: A Record of my Uproarious Years, (Englewood Heights, NJ: Prentice-Hall, 1957); Joseph F. Dinneen, The Purple Shamrock: The Hon. James Michael Curley of Boston, (New York: W. W. Norton, 1949); Lawrence J. Goodrich, “Boston’s Powerful Rogue”, The Christian Science Monitor, Dec. 29, 1992; National Governors Association, “Gov. JAMES M. CURLEY”; Lewis Woodspecial, “CURLEY IS JAILED IN DANBURY, CONN.”, New York Times, June 27, 1947.