Eminent Domain Part 1: Origins

Eminent domain is the right of the state to seize the private property of an individual for a public purpose with just compensation. This article will trace the origins of the concept from Ancient Roman law to its use in Early Modern states.

The formal concept of eminent domain is relatively modern. However, de facto versions of what we now call eminent domain in the U.S. have occurred throughout history. Eminent domain is somewhat unusual from the perspective of European law, the precursor of U.S. law. Most modern law codes in the West descend from Rome’s Civil Law. The concept was not formalized in the Roman Empire. Despite this, the concept does pop up briefly in the Roman Republic.

About fifty years before the Republic began to unravel, the system was showing cracks. Roman law originally had been developed to manage a tiny city-state. By 130 BCE Rome was no longer a little town on the Tiber. It was a Mediterranean empire that was conquering every serious threat to its sovereignty. In this period, patricians (the upper class) had consolidated ownership over vast swaths of land. This was in violation of laws limiting the size of individual holdings. The Gracchi brothers, Tiberius and Gaius, proposed what was probably the first use of eminent domain in history. Tiberius proposed state seizure of lands over the allotted maximum area so they could be returned to the ownership of normal Roman citizens. Both were elected Tribunes of the People with the hope they would implement these reforms. But they were murdered as a result. The deaths of the two Tribunes is often seen as the beginning of the end of the Republic. Their proposals were visionary, and incredibly equitable coming from a patrician family. Threatening to take the property of Senators was ultimately enough to instigate violation of their Tribunal right of inviolability (not to be touched). This would begin the unraveling of republican norms leading to empire.

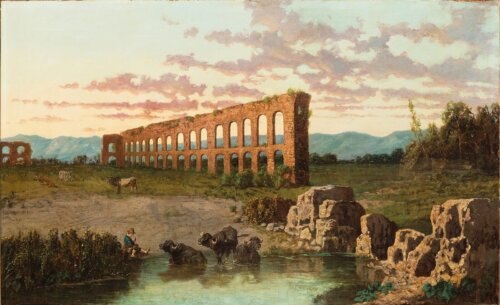

Most other pre-modern examples of involuntary land redistribution involve military action. They don’t usually involve a state taking private property from its own citizens. After the Gracchi, actions similar to eminent domain in Roman territories typically occurred through accommodation of a right. Rome’s famous roads, walls, and aqueducts were technically owned by the property owners whose land they crossed. In exchange for their maintenance, owners received tax abatements.

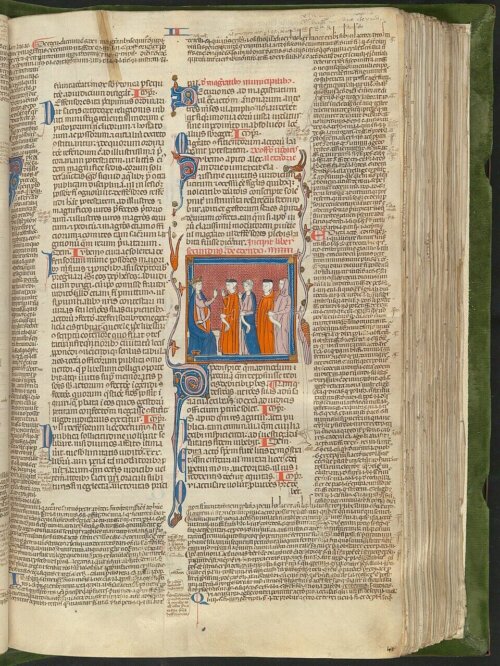

The eastern Byzantine Empire continued to use the Greek translation of Roman law, the Code of Justinian, until the fall of Constantinople in 1453. After Rome’s decline in western Europe, versions of Roman law continued to be loosely applied in the splintered kingdoms that began to develop. These early feudal kingdoms would evolve into states like Spain, France, Italy England, and Germany over time. They maintained some aspects of their Germanic culture while integrating into the remains of the Roman political systems. However, eminent domain is not among these laws.

In the Middle Ages, it had little relevance. Decentralized monarchs managing landholders through individual contracts of fealty did not need to use it. The King of France would not take land from his vassal the Duke of Aquitaine as the latter might see that as a breach of contract and start a revolt. Until modern centralized states began to form, eminent domain wouldn’t have made much sense. While Ancient Rome had to respect property, the Medieval Holy Roman Emperor, conversely, could simply ignore any “private” property when building something new. Sometimes the empire would instead deny that the owner had a right to their property at all. Versions of eminent domain began to appear in the 1300s, but they weren’t properly codified until the reign of Louis XIV of France (r. 1643-1715) . Louis XIV’s reign functionally made France into a modern state, and his legal system held the first law equivalent to modern eminent domain.

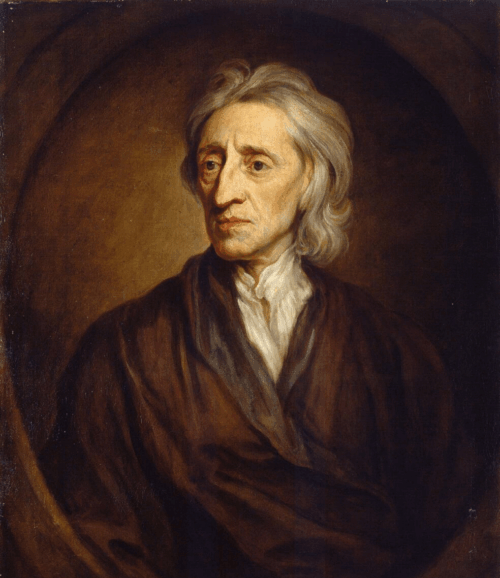

The meaning of private property wasn’t fully fleshed-out until the Enlightenment. Theorists John Locke and Thomas Hobbes, who generally had very different perspectives, agreed that private property rights could only exist if the government chose to recognize them. The state also needed enough power to enforce that recognition, even if it was against its own interests. This theory translated to reality, but it also led to a new means of public improvement. As centralizing states began to formally recognize property, they also started looking for ways to seize it back to build public works.

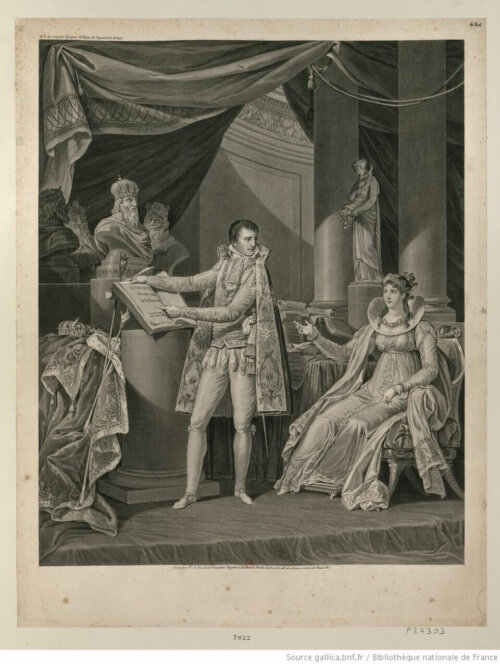

After the French Revolution, Napoleon Bonaparte reorganized the French state. He adjusted Louis XIV’s law to use the term eminent domain for the first time. Though the Napoleonic code came after the adoption of the U.S. Constitution, the term has been retroactively applied to the Fifth Amendment. The language in the Constitution uses similar language to Louis XIV’s legal code. France formalized judicial authority over eminent domain in 1810, at about the same time the U.S. developed the same process. Spain established eminent domain in 1836. In Prussia (the predecessor to modern Germany), eminent domain wasn’t established until 1874. Russian state ownership survived into the Soviet era and thus the power wasn’t established until 1994.

The next article will discuss how eminent domain came into existence in the United States. How would a nation built on the premise of the rights to life, liberty, and property deal with a government taking property away from private citizens?

Article by Sebastian Belfanti, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources:

Ferdinand Addis, The Eternal City: A History of Rome, (NY and London: Pegasus Books, 2018); Civil Code of the Russian Federation; Bell Carrington Price & Gregg, “What is Eminent Domain?”; Nick Dancaescu, “The Genealogy of Eminent Domain” (Gray & Robinson); Justica, “Kelo v. City of New London”; Stanley I. Kutler, Privilege and Creative Destruction: The Charles River Bridge Case (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971); James Madison, The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution; Carla T. Main, Bulldozed, (NY: Encounter Books, 207); William D. McNulty, “Eminent Domain in Continental Europe”; William D. McNulty “The Power of “Compulsory Purchase” Under the Law of England” ; Oyez, “Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff”.