Eminent Domain Part 2: Use in Early America

Eminent domain is the right of the state to seize the private property of an individual for a public purpose with just compensation. This is the second article in a series of three. This article will discuss the use of eminent domain in the early decades of the United States and a Supreme Court case based in the West End which set important precedents.

Note: This article follows the common practice of referring to the part of the Fifth Amendment relating to property as eminent domain.

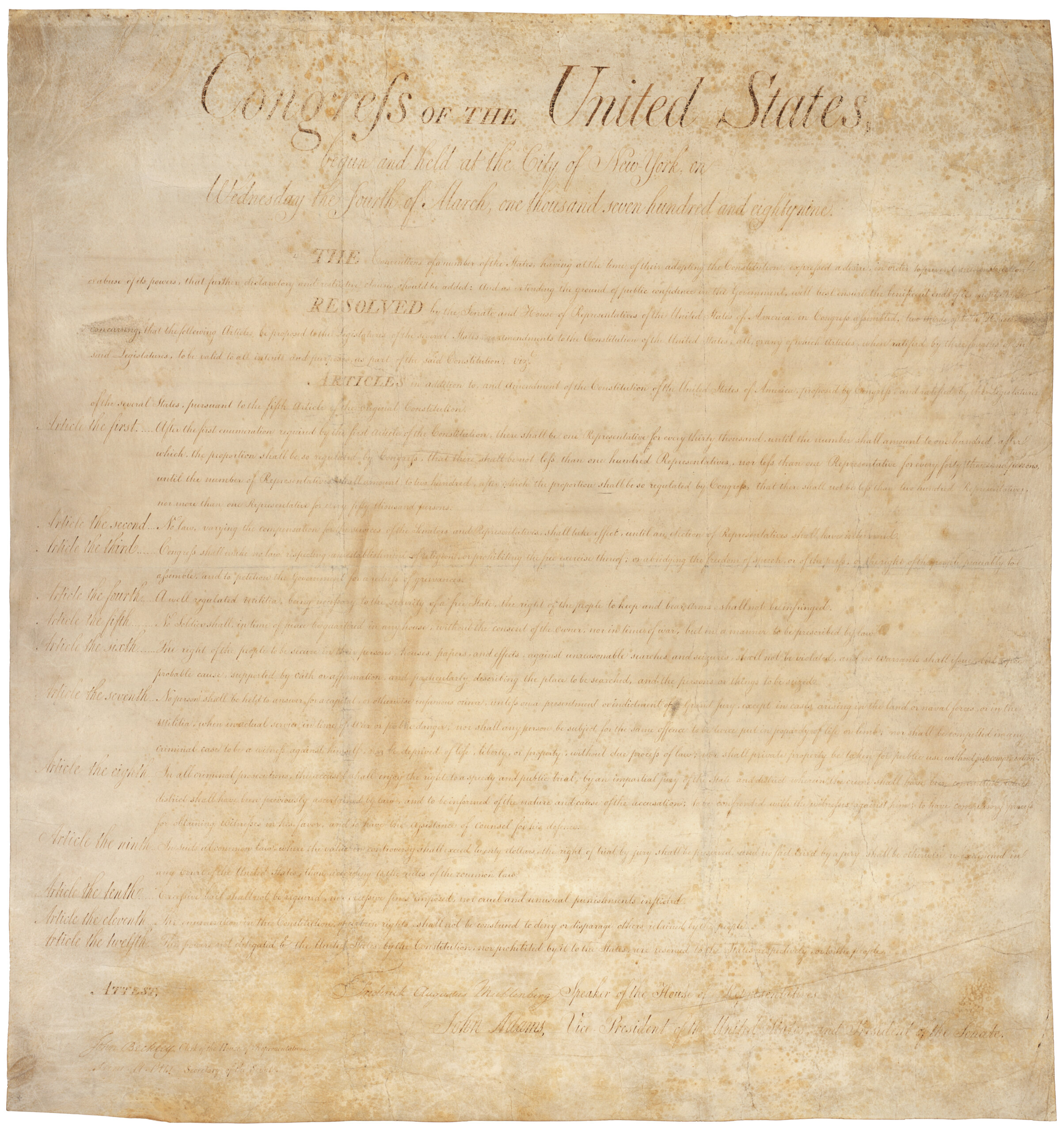

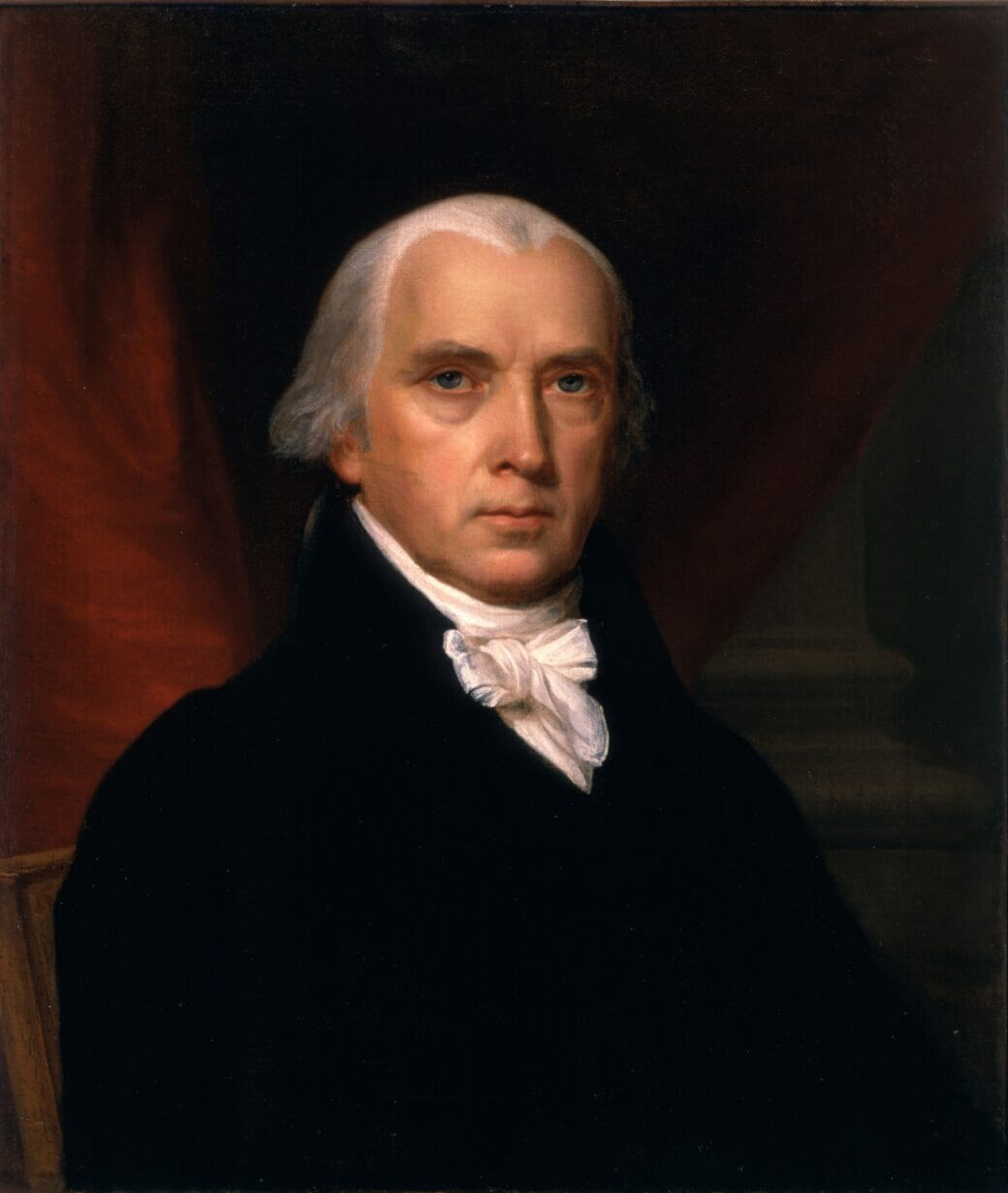

After the Revolutionary War, land ownership was a topic of substantial dispute. The newborn country took British loyalist lands without compensation (and with great enjoyment). Once this distribution was over, states continued to use eminent domain freely. Often they would seize land without compensation. James Madison recognized that this approach to private property was not sustainable. Plus, as a large landholder, he feared that the “mob” (common vernacular for unlanded citizens at the time) would someday seize his property. He had the opportunity to protect private property while writing the Bill of Rights in 1789. Almost all of the first ten amendments to the Constitution were composed from suggestions sent to Madison from across the country, as intended. The power of eminent domain was not suggested in a single letter. Madison, however, took a big political risk and added the provision on his own.

The final section of the Fifth Amendment formally enabled eminent domain in the United States (emphasis added):

“No person shall be held to answer for a capital, or otherwise infamous crime, unless on a presentment or indictment of a Grand Jury, except in cases arising in the land or naval forces, or in the Militia, when in actual service in time of War or public danger; nor shall any person be subject for the same offence to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

Madison intended the compensation clause – “nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation” – to guarantee the protection of private property rights without preventing the country from building roads, canals, and manufactories. Madison’s views on eminent domain changed substantially after he wrote the Fifth Amendment. By the end of his life, he realized that while the law mostly protected wealthy citizens from mob rule, it allowed for seizure of land from small property owners too easily. America was becoming a country where a lot, perhaps most, people owned some land. There was no precedent for democratic landholding in Europe. Thus Madison overlooked the potential disaster he had built into federal law. As we will see, Daniel Webster noticed it.

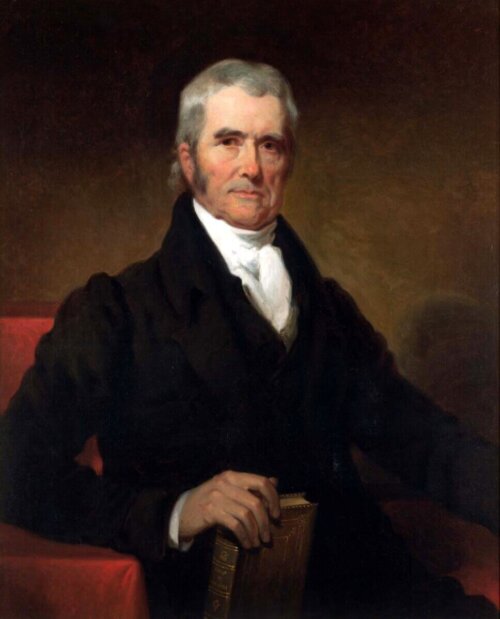

Chief Justice John Marshall was the fourth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, but from a functional standpoint he was its founder. The Marshall Court established the Supreme Court’s ability to rule on the constitutionality of laws. Before this, the court’s purpose was extremely unclear. Marshall wanted to establish the strength of the federal government. While he and the other justices did this independently, Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts brought numerous cases before the court that helped establish this authority. Marshall and Webster, with notable support from Justice Story, established strong rights for private citizens, and elevated federal law over state law.

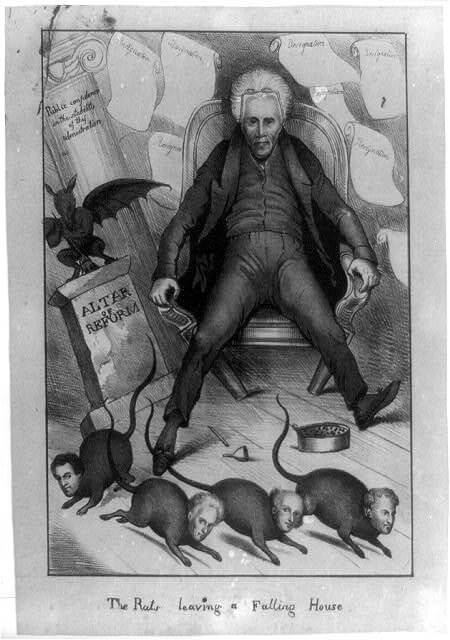

When Marshall died, President Andrew Jackson aimed to appoint justices who would roll back the Marshall Court’s work. Chief Justice Taney would be the leader of this shifting interpretation of constitutionality. However, he was far less critical of Marshall’s rulings than Jackson had hoped.

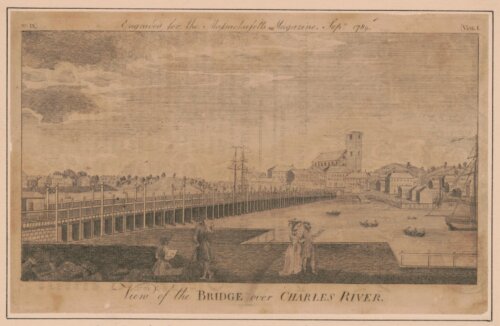

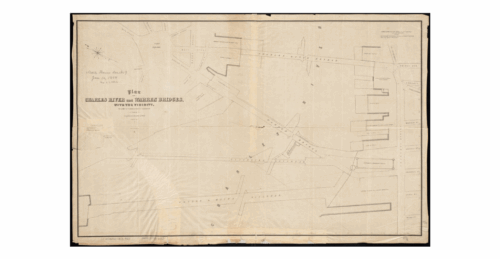

During Marshall’s tenure Webster had brought a case called Charles River Bridge v. Warren Bridge to the Marshall Court, but a number of mishaps prevented a ruling. It fell to Taney to decide the case in 1837, meaning Webster’s arguments would now face a far less receptive court. The case had to do with a dispute between two bridges in what is now the West End. (These bridges would be replaced in the 21st century by the Bill Russell and Zakim bridges). The Charles River Bridge company built a bridge in the 1780s between Boston and Charlestown and collected tolls with the permission of the Massachusetts Legislature. Then in 1828, the legislature chartered the Warren Bridge Company to build a free bridge. This would obviously reduce the first bridge’s revenue. Very few people would use a bridge they had to pay for when there was a free bridge less than 100 yards away. The Charles River Bridge Company sued on the basis that the legislature had breached its contract.

When the suit reached the Supreme Court, Webster argued for an interpretation of eminent domain that was in favor of investors and owners. He proposed that the “vested rights” (existing business) of the Charles River Bridge had been functionally seized by the Massachusetts Legislature when they chose to allow the construction of a nearby free bridge. The landmark ruling created a number of important precedents. Among them, the court found that a state was only required to compensate for physical land taken. The loss of business would not be compensated. The decision opened the gates for public takings. If there was no need to compensate for anything but the literal land and property taken at the time of seizure, then local governments could take land for relatively little. For example, a farm might be seized for the (low) value of agricultural land. If the farmer tending that land happened to be making a substantial profit from it, too bad, that isn’t part of the calculation. The ruling also indirectly supported a future element of eminent domain takings: that value of a seized property would be calculated as its value at the time of seizure. That made Madison’s fear a reality, since it would not include the people losing property in any public benefits derived thereof.

The early precedents set by the Supreme Court opened a path for a broad eminent domain power. A century later urban renewal would turn that path into a highway.

Article by Sebastian Belfanti, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Ferdinand Addis, The Eternal City: A History of Rome, (NY and London: Pegasus Books, 2018); Civil Code of the Russian Federation; Bell Carrington Price & Gregg, “What is Eminent Domain?”; Nick Dancaescu, “The Genealogy of Eminent Domain” (Gray & Robinson); Justica, “Kelo v. City of New London”; Stanley I. Kutler, Privilege and Creative Destruction: The Charles River Bridge Case (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1971); James Madison, The Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution; Carla T. Main, Bulldozed, (NY: Encounter Books, 207); William D. McNulty, “Eminent Domain in Continental Europe”; William D. McNulty “The Power of “Compulsory Purchase” Under the Law of England” ; Oyez, “Hawaii Housing Authority v. Midkiff”.