The Thriving Jewish Marketplace of the Old West End Part One: Peddler to Proprietor

This article is the second part of a series exploring Jewish life in the Old West End. The first part explored the synagogue life in the neighborhood. This introduction to Jewish businesses in the West End explains the economic path many immigrants traveled to achieve economic success. It also outlines the impact of Jewish businesses in the West End’s commercial center.

For over half a century, Boston’s West End buzzed with the energy of Jewish commerce. From the 1890s through the late 1950s, Jewish businesses on Spring Street were more than a place to shop. There, Eastern European immigrants could rebuild their lives, create economic opportunity, and forge a vibrant community. As actor Leonard Nimoy, who grew up at 87 Chambers Street, described, the West End had a “village life—a small-town feeling within the city.”

The Jewish Path to Economic Stability

The Jewish businesses that lined the West End’s streets were the result of a remarkable economic journey. The trajectory of one Jewish immigrant illustrated this pattern. He “started out as a peddler, later became manager of a cap making factory, then a delicatessen owner and eventually a private banker and steamship ticket salesman.” This evolution took years of grueling work. Yet, it offered something out of reach in the “old world” : the possibility of advancement through one’s own efforts.

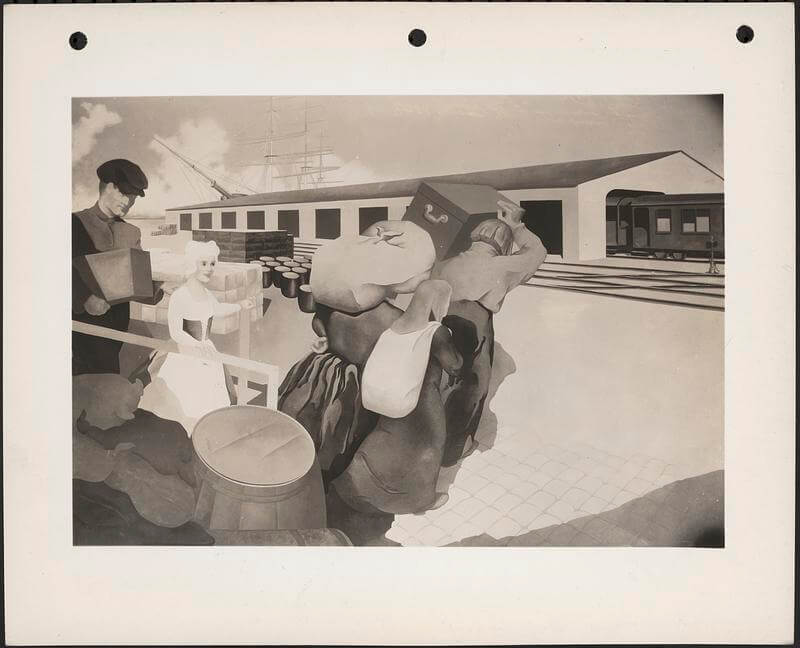

The trades Jews gravitated towards in their early years generally required little money to start and allowed immigrants to use old-country skills while learning English and American business practices. Most began as peddlers. They trudged through the city and countryside with packs of dry goods, notions, and household items strapped to their backs. This lifestyle exacted a heavy toll on Jewish families. Men spent weeks or months traveling rural sales routes away from home. These absences strained marriages and fractured families. By 1911, the problem had grown severe enough that Jewish groups founded the National Desertion Bureau. The Yiddish newspaper Forverts (Forward) ran a regular feature called “The Gallery of Vanished Husbands.” It featured photographs of men who had abandoned their families. The domestic cost of economic survival was a real concern within the community.

Yet for those who persevered, peddling provided crucial funds that could be used to purchase a pushcart. Then they could establish small shops like those on Spring Street. Finally, the most successful could open larger stores or a factory. Some would, however, remain wage laborers their entire lives. By the 1890s, Boston had become an important clothing center, and Jewish immigrants dominated this industry. The “katerimjke” (sewing-machine trade) employed thousands of Jewish workers, particularly Russian Jews, in factories and tenement workshops.

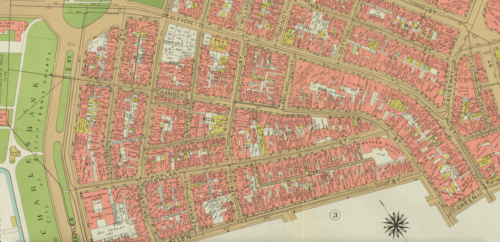

This economic mobility shaped residential patterns. As historian Isaac Fein observed, immigrants who started as factory workers in the worst neighborhoods eventually made their way to “nicer ghettoes”. They started in the South End, then the West End, then moved to places like Roxbury. The West End was thus a way station where immigrant Jews with some economic success could establish themselves and their families. The community also maintained a strong emphasis on education. Children attended public school and many achieved remarkable success in later life as doctors, lawyers, teachers, and business owners who moved to more affluent neighborhoods.

From North End Overflow to Immigrant Hub

The West End’s transformation into a predominantly Jewish neighborhood occurred rapidly. Around 90,000 Jews fleeing anti-Semitic laws and persecution in the Russian Empire landed at the port of Boston between 1880 and 1914. Though fewer than half of these incoming immigrants remained in Massachusetts, thousands settled in Boston. Most initially settled in the South End and North End before the West End became their primary destination.

By 1895, the West End’s population numbered 23,000, with 6,300 mostly Russian and Polish Jews. This number surged dramatically over the next fifteen years due to chronic overcrowding in the North End and the catastrophic 1908 Chelsea Fire which displaced Russian Jewish families. By 1910, thousands of Russian Jews had moved to the West End, transforming the neighborhood. Eastern European Jews eventually constituted about 25% of the West End’s population. This made them the largest group in a district that housed 23 different ethnic groups.

Mary Jackman, who was born in the West End in 1902, remembered the arrival of Jewish families. She recalled, “We’d try to teach them English. We’d give them candy and make them say ‘candy’ before we’d give it to them. We’d give them a pickle and they couldn’t say pickle. Some of those are millionaires today and we had to teach them English.”

Economic Foundations and Occupational Diversity

Jewish immigrants in the West End worked in dozens of occupations. They were peddlers, shoemakers, carpenters, roofers, cigar makers, tailors, antique dealers, grocers, jewelers, bakers, newsboys, sweatshop owners, and kosher butchers. Weekly wages ranged from $6 to $15 depending on occupation. These were modest sums that still represented economic opportunity unavailable in Europe.

Property ownership records show economic success. Between 1885 and 1905, Jewish ownership increased dramatically. By 1905, Jews constituted the majority of real estate owners in the West End. At the same time American-born and Irish-born property ownership fell as these established groups migrated out of the neighborhood.

Spring Street: The Commercial Heart

Spring Street was the West End’s commercial hub. Peddlers displayed their goods in barrels and boxes on the street like in a European market. The street was a culturally accessible business environment. Delicatessens served corned beef on warm rye while bakeries filled the air with the scent of fresh challah. In the kosher butcher shops, customers, like Nimoy’s grandmother, conducted their business in Yiddish without having to speak any English.

The cultural exchange worked both ways. Nimoy remembered an Italian iceman who learned Yiddish to speak to his Jewish customers. Vendors came down the streets calling out in Yiddish—”Do viber, viber!” (meaning “ladies, ladies!”)—selling thread, needles, cloth, and ribbons.

As Jim Campano observed, the neighborhood’s diversity was its strength. Many groups coexisted “all living together in one neighborhood.” They did business with each other and created a tight-knit community.

Legacy: From Peddler's Pack to Property Owner

The Jewish businesses of the West End represented the immigrant journey from poverty to stability, from outsider to community pillar. The progression from peddler to property owner played out on the streets of the West End hundreds of times. Each successful transition was the result of years of grueling work, family sacrifice, and determined saving.

The social cost of this economic advancement was real. Fathers spent weeks on the road and mothers worked long hours in tenement sweatshops. Children could even leave school early to contribute to family income. Yet these sacrifices enabled the next generation to achieve professional success.

The West End’s Jewish businesses built a community where immigrants found connection, support, and belonging in addition to their groceries. The delicatessens, bakeries, butcher shops, and pharmacies that filled the West End supported the community. There, Jewish West Enders could speak Yiddish, extend credit to families in need, exchange the news, and face the challenges of immigrant life together.

Former West Enders still speak with passion about the sounds and smells of Jewish shops on Spring Street. They remember a time when everyone knew shopkeepers by name. Those shopkeepers were the children and grandchildren of immigrants who had arrived with nothing but a peddler’s pack and a determination to build a better life.

Article by Amir Tadmor, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Santo J. Aurelio “Jews and Italians in the West End of Boston, 1900-1920” May 7, 1984, The West End Museum Archives; Meaghan Dwyer-Ryan “Ethnic Patriotism: Boston’s Irish and Jewish Communities, 1880-1929,” dissertation, (Boston College, August 2010); Isaac M. Fein, Boston: Where It All Began – An Historical Perspective of the Boston Jewish Community (Boston Jewish Bicentennial Committee, 1976); Forṿerṭs (Forward) newspapers, 1900-1958, from Historial Jewish Press, The National Library of Israel and Tel Aviv University; Mary Jackman, “Bruno Interview 0018,” October 8, 1980, The West End Museum Archive; Eric Moskowitz, “Boston’s Last Tenement – an Island Awash in Modernity,” Boston Globe, August 15, 2015; Leonard Nimoy and Christa Whitney, “Leonard Nimoy Remembers Boston’s West End Neighborhood” (Yiddish Book Center, February 6, 2014); Josie Savage, “Bruno Interview 0029”, October 24, 1978, The West End Museum Archive;Jeanne Schinto, “Israel Sack and the Lost Traders of Lowell Street” Maine Antique Digest, April 2007, accessed from the West End Museum Archive; The West Ender Newsletter, 1985-2022; Yivo Institute for Jewish Research, “Runaway Husbands, Desperate Families: The Story of the National Desertion Bureau”, exhibit, on view June 17, 2024 – May 20, 2025.