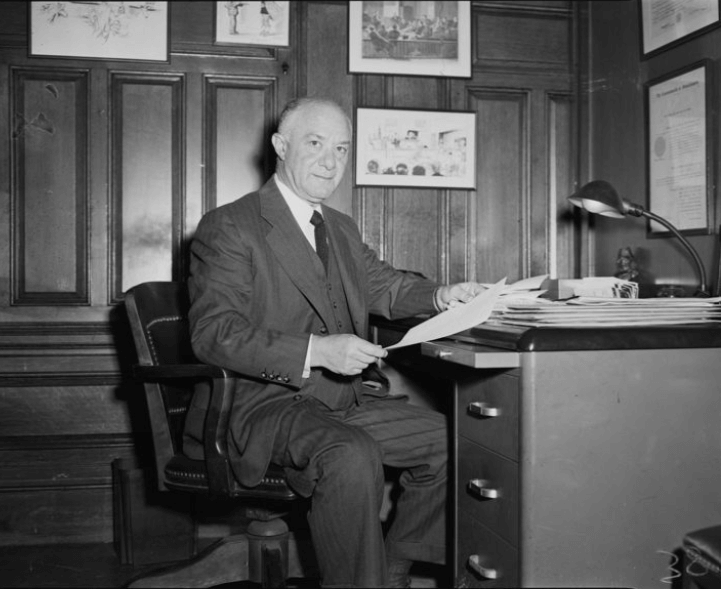

Judge Elijah Adlow

Elijah Adlow, born in the old West End at the turn-of-the-century, had a long career as Chief Justice of the Boston Municipal Court, yet made decisions as a judge that have a questionable legacy.

Elijah Adlow was born on August 15, 1896, in the old West End, to Nathan Adlow, who immigrated from Poland, and Bessie Adlow, who immigrated from Lithuania. Adlow’s great-grandfather lived in the old West End, and other members of Adlow’s extended family lived throughout the neighborhood, “on Barton Court, Leverett Street, Chambers Street and Allen Street.” Adlow recalled in a 1967 speech before the West End Old Timers at Boston’s Somerset Hotel about the neighborhood. Although Adlow remembered the West End fondly, he was mostly raised in Roxbury after his immediate family soon moved there. Adlow graduated from English High School (then located on Warren St. in the South End, adjacent to Boston Latin), and later attended Harvard where he graduated in 1915. Adlow then graduated from Harvard Law School in 1917 and served in the Navy in World War One.

Adlow served as a Republican in the Massachusetts State House for the 16th Suffolk District from 1921 to 1926, and as special counsel for city government from 1927 until his first judge announcement in 1928. Adlow was appointed Chief Justice for the City of Boston’s Municipal Court in 1954, and stepped down from the bench in 1973. During World War Two, he was on staff for the Adjutant General’s Department, which managed human resources and personnel for the Army. He was also a prolific writer of four books, Policemen and People (1947) Napoleon in Italy, 1796-97 (1948), The Genius of Lemuel Shaw: Expounder of the Common Law (1962), and Threshold of Justice: A Judge’s Life Story (1973). Although in Policemen and People Adlow argued that “when group tensions are very evident wherever we turn…no program directed to their solution can ignore the part played by the the police in aggravating or reducing them,” he strayed from his belief in less aggressive policing when commenting in 1969 that he was “sick and tired of having federal court judges interfering with the enforcement by police of the law in this city and state.” Adlow’s own rulings were permissive of police misconduct, most notably as the FBI and state Attorney General were beginning to investigate Boston police officer Walter Duggan for the murder of African-American soul singer Franklin Lynch.

Franklin Lynch, after releasing the hit song “Young Girl” in 1970, checked into the Boston City Hospital with a broken shoulder. Struggling with mental illness, Lynch acted erratically in the hospital and scuffled with another patient with mental challenges, but officer Duggan recklessly fired his gun five times into Lynch’s body after pushing him to the ground. Adlow ruled in Boston Municipal Court in 1970 that Duggan was justified in shooting Lynch to make an example of him to dissuade the patient he was originally watching over, Abdullah Hassan, from leaving his bed. Hassan was a robbery suspect healing from a knife wound, and as he attempted to leave the surgical ward while Duggan was distracted, Duggan pulled out his gun and ordered Hassan to stay back or be shot. Adlow rationalized Duggan’s decision to shoot Lynch on the premise that “the actual firing of the gun by Officer Duggan was justified in order to impress upon all the futility of what was being attempted.” He also claimed that Duggan would be “discredited” by his peers in the BPD if he did not fire his gun at all. For rulings such as these, Boston attorney Charles Dattola, who represented Lynch’s family in a civil trial soon after the ruling, said that “Adlow was a stone-cold racist.” Adlow did not extend the same leniency to criminal defendants that he gave to Duggan: the judge had also said that “Of the constituency that frequents criminal courts, very few are innocent…You don’t reform them.” A similarly intolerant ruling that Adlow made came from an obscenity trial on March 11, 1969, when he concluded that the film The Killing of Sister George was obscene enough to warrant a six-month jail sentence and $1000 fine for theater manager Joseph Sasso. Adlow argued that the film shown at Cheri Theatres was obscene because of its lesbian scene in the final five minutes, which Adlow described as “filth” that “revolted the body.”

Inflammatory opinions such as these gave Adlow frequent press coverage, as reporters liked his “Adlowisms,” the phrase of Boston Globe reported Edgar Driscoll, Jr. Adlow frequently had spectators at his sessions, and was known for making statements to defendants like one pickpocket with a long rap sheet: “You’ve been in court more than I have.” Although he drew admirers from the public and from newspapers, Adlow was often criticized by peers in the judiciary and even the Boston Bar Association for harming the reputation of judges in general. Adlowisms also included language typical of the thim’s politics, including statements about welfare, gangs, and “leniency in the home,” themes which he appealed to in his speech to the West End Old Timers. In their 1967 gathering, Adlow was critical of urban renewal for destroying a vibrant neighborhood with a rich immigrant history, but painted the old West End as the polar opposite of an American 1960s that he painted as degenerate, especially in his attitude toward anti-Vietnam War protests.

Elijah Adlow died from an ongoing illness at the age of 86 on November 4, 1982. He was married for fifty-five years to his wife, Jessie Adlow, with whom he had two daughters, Barbara Glazier and Elizabeth Lewis. He was one of the most legally influential, vocal, and controversial Bostonians to have been born in the old West End.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Threshold of Justice: A Judge’s Life Story (summarized on Wikipedia), Boston Magazine, Address to the West End Old Timers (1967, print), The Harvard Crimson, Boston Globe (Obituaries: “Judge Elijah Adlow, 45 years on the bench,” by Edgar J. Driscoll, Jr., November 6, 1982, 1.) Judge Elijah Adlow sitting at desk, wearing a suit. 23 Apr 1954. Web. 20 Nov 2020. <https://ark.digitalcommonwealth.org/ark:/50959/xs55nb74v>.