The Vilna Shul: The Last Immigrant-Era Synagogue in Boston

The Vilna Shul is the last remaining immigrant era synagogue in Boston, now serving as the Jewish cultural hub of Boston. Built to serve Jewish immigrants from the Vilnius (Vilna) community, the shul has stood for over 100 years. It contains important examples of Jewish folk art and has had an enduring commitment to community.

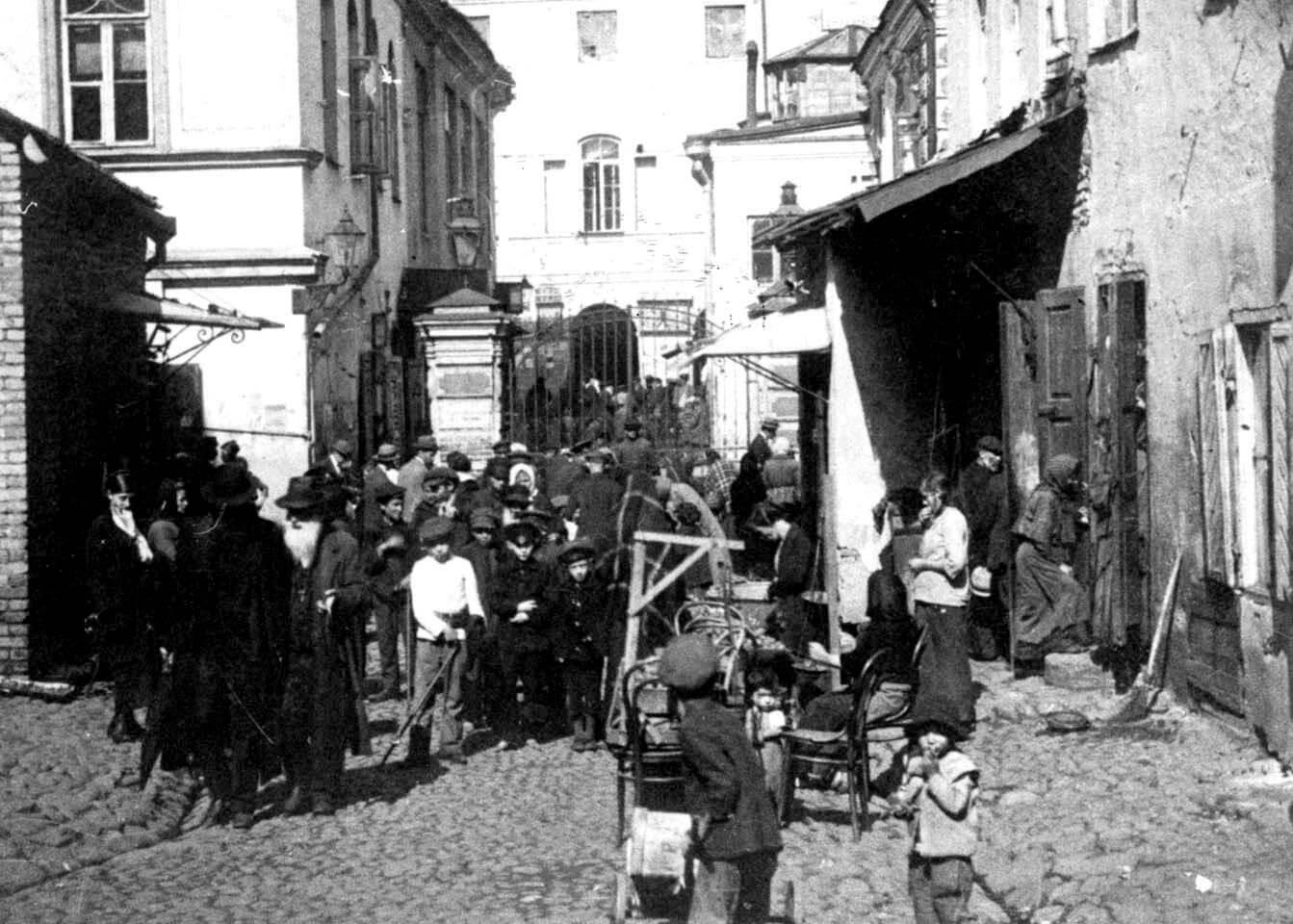

In the late 19th century, Jewish immigrants traveled from the province surrounding what is now Vilnius, Lithuania (“Vilna” in Yiddish) to the United States. Hoping for a new life, many families settled in Boston, especially in the West End. In 1888, they formed a landsmannshaft. This was a commonplace organization for immigrant Jews from the same area in Eastern Europe. It acted as a system of mutual aid and the landsmannshafts were often associated with an individual congregation. In 1893, the Vilner Congregation began meeting for services in members’ homes.

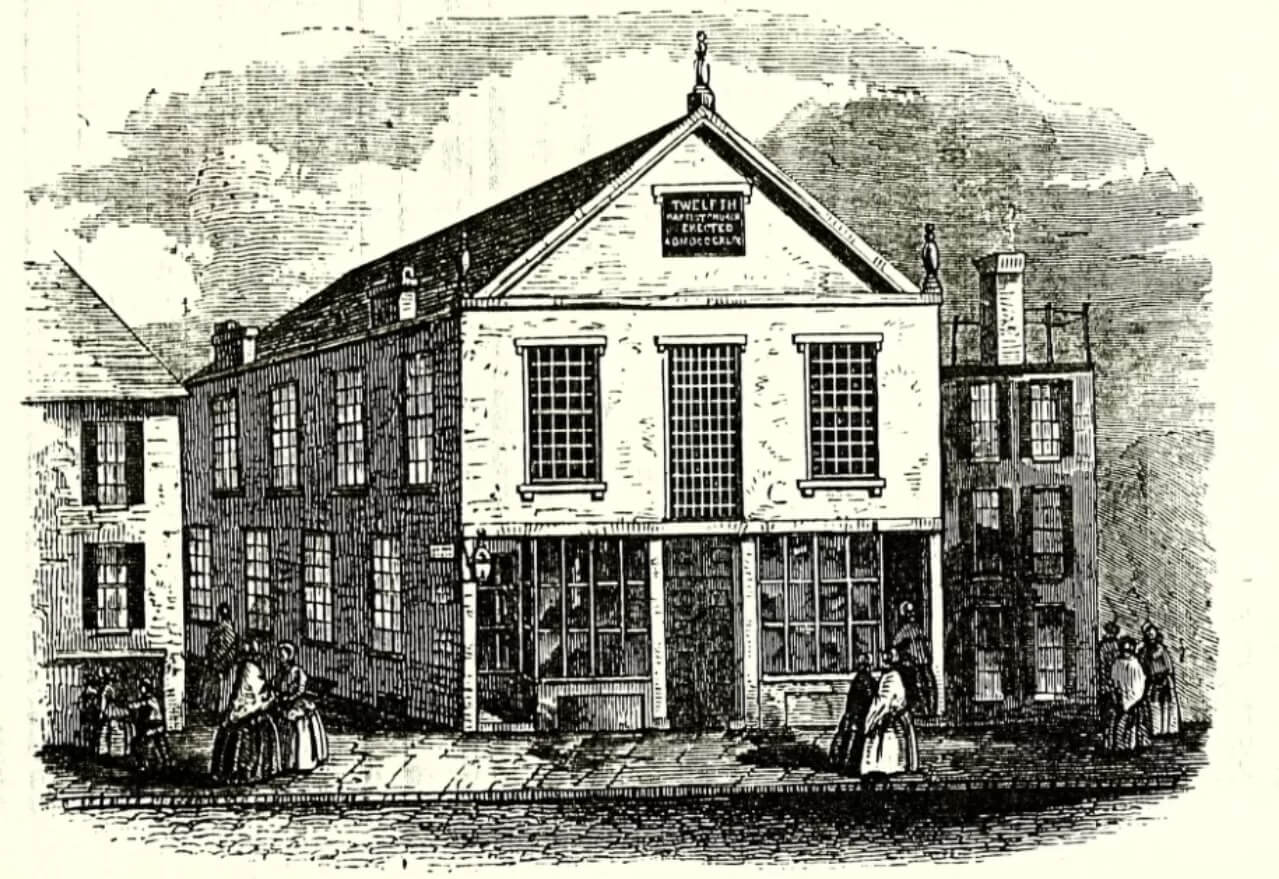

By 1906, their numbers had swelled. They needed their own synagogue. They first purchased the former Twelfth Baptist Church at 45 Phillips Street, which had been known as the fugitive slave church. Most of the Black community who had lived on the North Slope of Beacon Hill and worshiped at the church had moved further south as immigrants moved in.

Ten years after settling into the new shul, the city took the property by eminent domain to expand a school. The city gave the congregation $20,000 to leave their property. Eager to build their own center for Jewish life, immigrant families used the money to build a new synagogue on an L-shaped plot of land down the street. This layout was perfect for an Orthodox synagogue which needed a distinct men’s and women’s section. In 1919, the congregation laid the cornerstone at 18 Phillips Street. They hired Max Kalman, the only Jewish architect in Boston to design the new building. As part of the move, they carried over the original Twelfth Baptist Church’s wooden pews. Dating from the mid-19th century, the benches once seated self-emancipated slaves and volunteers in the Massachusetts 54th Regiment that fought in the Civil War.

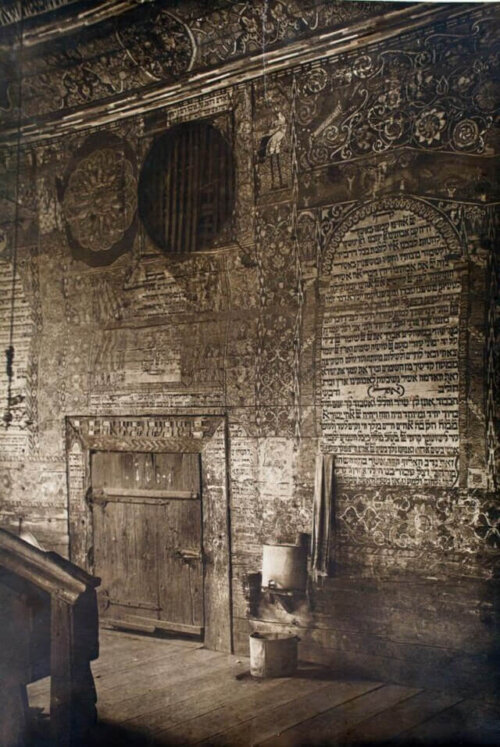

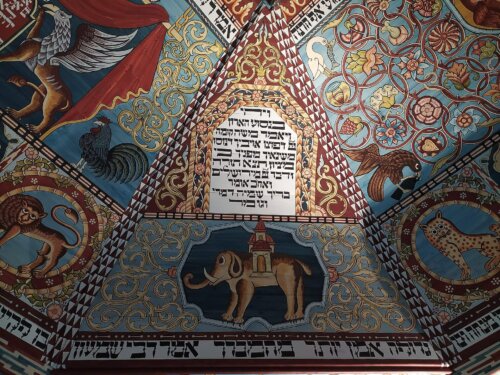

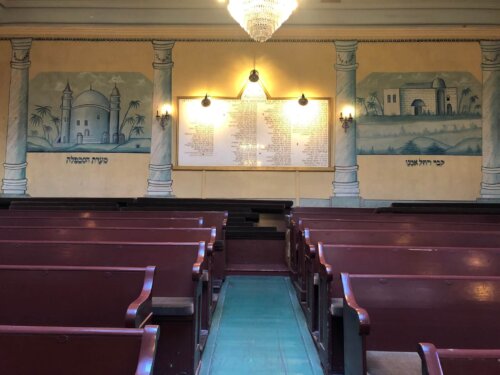

The interior of the shul was covered in immigrant folk art murals. This tradition of painted synagogues originated in Eastern Europe. It traveled to the United States with immigrants who brought over their old country’s traditions. Prior to World War II, a rich history of painted synagogues dated back hundreds of years in Eastern Europe. Seemingly plain wooden synagogues revealed interiors ornately painted with exuberant, colorful scenes. This rich cultural heritage was almost completely obliterated by the Nazi regime. The Vilna boasts three distinct layers of Eastern European-style murals making them rare survivors.

The community thrived in the 1920’s and 1930’s and came together to welcome Shabbat, celebrate simchas (happy occasions), and pray during the week. In subsequent decades, the community began to decline in numbers. Federal immigration quotas affected the number of immigrants who could enter the country. Urban renewal destroyed the West End and displaced the neighborhood’s immigrant community. By the 1980s, the Jewish community had long since left Beacon Hill and the West End, mostly for the suburbs. In 1985, the Vilner Congregation was the last of the seven West End immigrant-built synagogues to close. The last remaining member, Mendel Miller, held a service in the synagogue for the last time and locked the door.

The Vilna sat in disrepair for over 10 years until a small but mighty group of prominent Boston leaders undertook a dogged effort to purchase and restore the building. The Boston Center for Jewish Heritage was granted possession in 1995. They raised funds to replace the roof, rebuild windows, install a sprinkler system and new furnace. They undertook a massive clean up of the property to make it habitable and safe, which took nearly a decade.

In 1998, the first mural was uncovered and restored. Historians were shocked to find the murals as they altered previous assumptions about Jewish immigrant style in Boston. Earlier studies had believed that Jews in Boston had mimicked the more austere design of traditional New England meetinghouses in an attempt to assimilate. However, members of the Vilna Shul had opted for traditional Eastern European Jewish designs in bright pastels in their new synagogue.

In 2009, a grant from Partners in Preservation, a joint program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation and American Express, provided funding to uncover the oldest mural. This mural dated to around 1923 and decorated the back wall of the women’s section in the main sanctuary.

Today the Vilna is a non-profit organization committed to celebrating and honoring the rich diversity of the City of Boston. The Vilna, as the only immigrant-era synagogue remaining in Boston, is a contributing building in the Beacon Hill National Landmark District.

Among their programming is the the Havurah on the Hill group for young adults, originally formed in the spring of 2001. This monthly community-led service, held in the sanctuary, connects the young adult community in the historic building. The young adult group, alongside the Vilna Shul Board, works to restore and revive the Vilna Shul and to ensure that it will continue to exist for future generations.

In 2025, the Vilna merged with the Jewish Arts Collaborative to use the arts and culture to form connections. Today the synagogue is again filled with life as it hosts community programs, Jewish life cycle events, exhibits exploring Boston’s Jewish history, arts and entertainment, and monthly events for young people. The Vilna strives to give voice and meaning to the histories and experiences of Boston’s immigrants and newcomers. From its landsmannschaft roots to the present day, the Vilna Shul continues to be a hub for community, connection, and celebrations of all kinds.

Article by The Vilna Shul, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Malka Benjamin, Sue Gilbert, Dallas Kennedy, Michal Kennedy, Chelley Leveillee, Deborah Melkin, Robyn Ross, Atara Schimmel, Morris A. Singer, and Georgi Vogel Rosen, “Siddur on the Hill,” (The Vilna Shul, 2011; Leigh Blander, “New Life, New Vision for The West End’s Historic Vilna Shul,” (The West End Museum, June 14, 2022); Boston Women’s Heritage Trail, “Vilna Shul and Mary Antin”; Grace Clipson, “The Fugitive Slave Church: The Twelfth Baptist Church, Leonard Grimes, and Abolitionism in the West End” (The West End Museum, March 1, 2025); Jewish Virtual Library, “Landsmannschaften”, (Encyclopedia Judaica, The Gale Group, 2007); The Pluralism Project, “Vilna Shul,” (Harvard University, September 25, 2018); Jennifer A. Stern, “This Boston synagogue looks like a New England church but murals reveal its Jewish identity” (Forward, December 5, 2023); The Vilna Shul, “History”; Mordechai Zalkin, trans. Barry Walfish, “Vilnius”, (YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe).