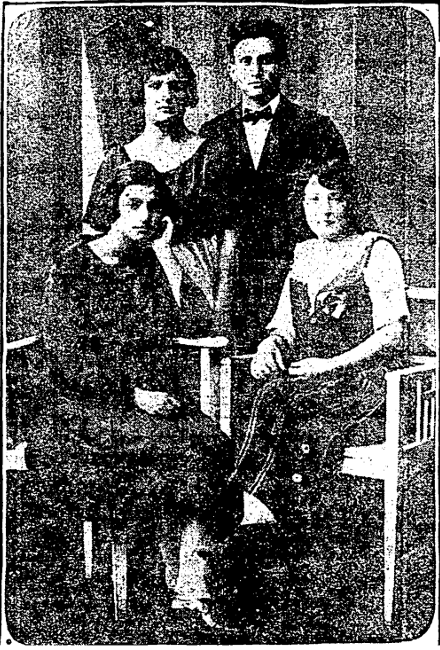

President Calvin Coolidge and the Klayman Family of the West End

In 1923, Annie, Jennie, and Rosie Klayman emigrated from Poland to reunite with their parents who lived on 16 Anderson St. in the West End. After arriving, the Klayman sisters were nearly deported because of restrictive immigration quotas, until President Calvin Coolidge intervened to let them stay in the United States.

On November 2, 1923, three Russian girls – sisters Annie Klayman (19 years old), Jennie Klayman (17 years old), and Rosie Klayman (12 years old) – arrived in Portland, ME on the SS George Washington. They had emigrated from Poland to reunite with their parents, Jacob and Gertrude Klayman, who lived at 16 Anderson Street in the West End. Jacob Klayman, born on April 10, 1882 in Novohrad-Volyns’ka (now Zviahel), Ukraine, immigrated to the West End in 1910. He worked pressing clothes for a tailor in order to make enough money to send for the rest of his family.

Klayman quickly realized that the United States, despite its opportunities, “wasn’t a land of as swift promise as he’d been led to believe,” according to the Boston Globe. Three years in, he could only pay for Gertrude’s voyage to the West End in 1913, leaving behind their three daughters in Rovna, Poland with their grandmother, Ida Klayman. In 1917, Ida died, and Annie, Jennie, and Rosie were left with a sister. When that sister later immigrated to America, the children were forced to stay with another relative in Warsaw.

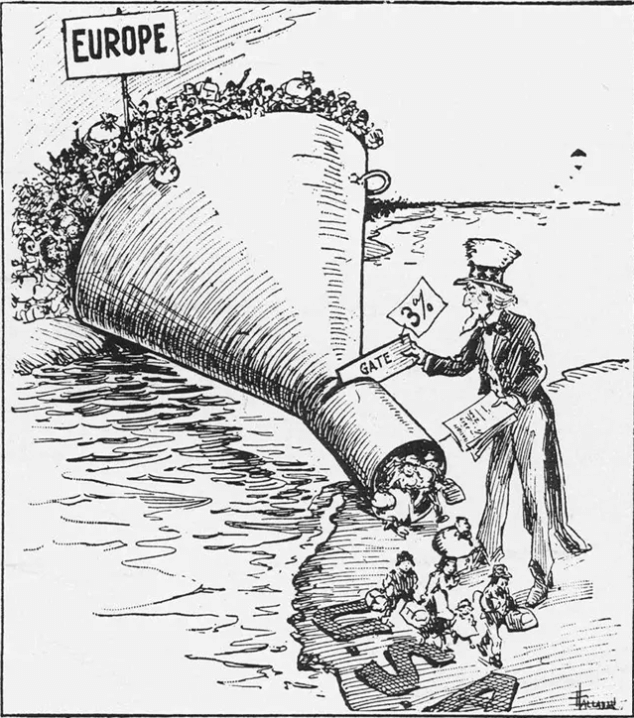

By 1923, Jacob Klayman had already submitted the paperwork to become a naturalized citizen, and he could finally afford to send his children to the United States, but a new restrictive immigration quota now blocked their entry. The Emergency Quota Act of 1921, a federal law, limited annual immigration to 3% from each country based on how many people of each nationality already lived in the US as of 1910. These restrictions, motivated by nativism, were biased against Eastern and Southern European immigrants (e.g. Russians and Italians) and favored those of Northern and Western European descent (e.g. British and Irish) who had greater numbers in the US. Recent immigrant arrivals who were already less represented numerically were the “undesirables” that the federal government sought to exclude, and in 1923 the Klayman sisters were wrapped up in this restrictive system.

Jacob and Gertrude Klayman were determined to save their daughters from deportation and to bring them to the West End. As Annie, Jennie, and Rosie waited in Portland for three weeks, their parents reached out to friends in Boston, including Aaron H. Werner from Allston. Werner was the “conveyancer” (a lawyer who managed real estate transfers) for the Boston Street Laying-Out Department. Both Werner and Boston Mayor James Michael Curley took an interest in the Klaymans’ case and sent letters to President Calvin Coolidge and William W. Husband, Commissioner-General of Immigration (appointed by Warren G. Harding). These letters were enough to convince Coolidge to intervene and allow Annie, Jennie, and Rosie Klayman to stay in the United States. According to the Boston Globe:

The powers at Washington were moved by the facts presented. The girls were minors and the father was a hard-working pressman. They had been separated for 13 years. The mother hadn’t seen her daughter for 10 years. A letter from Commissioner Husband to Mayor Curley announced that orders to admit Annie, Jennie, and Rosie had been given. Two letters came from President Coolidge’s office–one promising investigation of the case and the other saying that the girls would be admitted.

While Calvin Coolidge was willing to reunite the Klayman family in the West End, he remained a nativist who subscribed to xenophobic immigration restrictions. In his “First Annual Message” on December 6, 1923, President Coolidge declared that “America must be kept American. For this purpose, it is necessary to continue a policy of restricted immigration.” Coolidge signed into law the Johnson-Reed Act of 1924, which created more restrictive quotas set at “two percent of the total number of people of each nationality in the United States as of the 1890 national census.” The Johnson-Reed Act, which also set a stricter yearly cap on the total number of immigrants regardless of national origin, deepened federal bias towards immigrants from Northern and Western Europe instead of Eastern and Southern Europe. The Klaymans, meanwhile, were happy to be able to give Annie, Jennie, and Rosie their first American Thanksgiving. The sisters were thankful to be reunited with their family, including cousins, and to eat turkey. A Boston Globe reporter who visited the family in the West End thought that “there, in the humble, dingy home at 16 Anderson St. will be one of the most genuine Thanksgiving feasts in the city.”

President Calvin Coolidge passed away on January 5, 1933. On January 8, Aaron Werner offered one of “the sincerest condolences forwarded to Mrs. Grace Coolidge in her bereavement” for what President Coolidge did for the Klayman family. Werner, according to the Globe, was “prompted by his own admiration for Mr. Coolidge’s kind-heartedness, and that of the three Klayman sisters.” By 1933, Annie, Jennie, and Rosie Klayman were all residents of Greater Boston, and naturalized citizens, with spouses and children.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Geni; National Park Service; Pew Research; ProQuest/Boston Globe (“President Made Their Thanksgiving Real One,” November 29, 1923; UVA Miller Center; Smithsonian Magazine; “Werner Recalls His Aid to Three Alien Sisters,” January 8, 1933).