Allen Street House: Early Autopsies, Morgues, and Pathology at MGH

The Allen Street House, built in 1874 at Massachusetts General Hospital, became the center of early pathology and autopsy practices in Boston. The House’s morgue, autopsy amphitheater, and laboratories were used for experiments, research, and education. For over 80 years, it served as the symbolic and functional heart of the hospital’s pathology department, shaping both clinical knowledge and medical teaching.

Autopsy at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) can be traced back to around 1835. During this period, pathology centered on the autopsy, as surgical pathology did not develop until the late nineteenth century. At the time, MGH was the only hospital of the Harvard Medical School (HMS), and in 1847, HMS moved to North Grove Street, next door to the Bulfinch Building of Mass General. HMS’s Department of Pathology was officially created that same year, and it became the first medical school in North America to teach pathology as a special course.

In 1874, work commenced to create a physical home for the first significant pathology facilities at MGH. As that year’s Annual Report of the Trustees described: “A new autopsy building was begun in August, and is now nearly ready for use, costing seventeen thousand dollars ($17,000.00). It is built of brick, 45 feet square by 26 feet high, it contains receiving rooms, a theatre with seats for 165 students, and rooms for the Pathological Cabinet. By a vote of the Trustees this building will be called the ‘Allen Street House’.” In the years to come, “Allen Street” would become essentially synonymous with the Department of Pathology, and the phrase “Discharged to Allen Street” a common euphemism for indicating the death of a patient. Indeed, until recently, MGH patient charts were stamped “Allen Street” when a patient died — an allusion to the location of the Pathology department from 1874 to 1956.

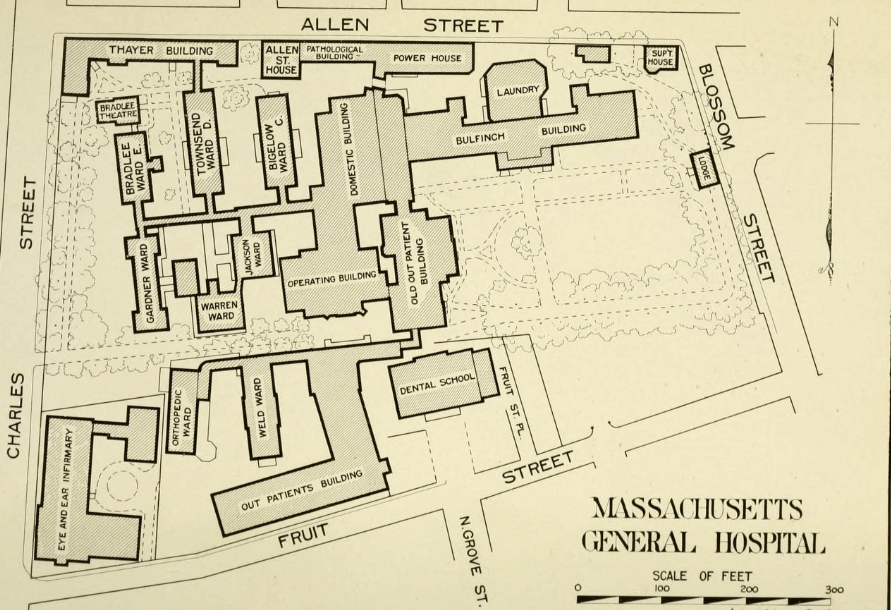

The Allen Street House was completed in 1874, built on Allen Street (now Blossom Street) at the north border of MGH’s grounds. It was on the hospital side of Allen Street, just west of the Bulfinch Building. In creating this physical space to accommodate an amphitheater, morgue, and small laboratory, the Trustees aimed to have “kept in view the two purposes of a hospital set forth in the circular of Dr. James Jackson and Dr. John Collins Warren published in 1810, viz., to succor the poor in sickness, and to promote facilities for students to acquire medical knowledge.”

However, by the early 1890s the Allen Street House was already technologically and spatially inadequate for the hospital’s growing needs, particularly as laboratory diagnosis became a more integral component of hospital diagnosis. In response, the Trustees began to fundraise for a laboratory fund that would allow for the construction of new facilities and designated money to pay for pathologists to study in cutting-edge European laboratories. In 1896, the renovated Allen Street House reopened with a new Clinico-Pathological Laboratory inside it.

The aim of the Allen Street Building and the newly-formed Pathology department within it was, according to Dr. James Homer Wright, to “give to the hospital the benefit of those modern microscopical, bacteriological, and chemical methods which are of such great importance in the diagnosis and study of disease.” Autopsies were vital to this medical advancement. Consequently, the original Clinico-Pathological Laboratory was connected to the building in which autopsies were performed.

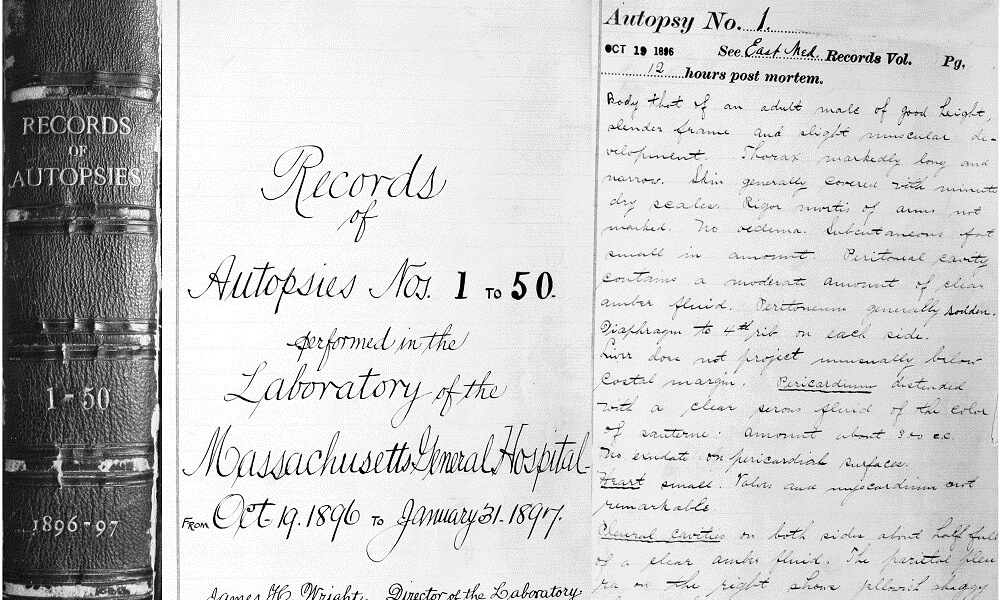

The first MGH autopsy with detailed records took place in the renovated Allen Street House on October 19, 1896. The report, outlined in neat longhand, begins with an external examination before moving into analysis of the organs. It concludes with six anatomic diagnoses: acute miliary tuberculosis, chronic tuberculosis of several lymph nodes groups, chronic localized tuberculosis of the lung, ascites, pleuritis, and miliary abscess of the kidneys. Sections from the man’s spleen and caseous lymph gland were then cultured into a guinea pig for testing. Seventeen days later the guinea pig was “found gasping” and its autopsy showed tubercle bacilli on smears of necrotic lymphoid tissue.

By 1905, the amount of autopsies swiftly increased. From 1897 until 1904, autopsies were performed in about 30 percent of deaths, but by the second half of 1905, this number had increased to 70 percent. Soon, however, this percentage decreased again, as the Pathology department was prevented from performing medicolegal autopsies. Nevertheless, by April 1921, Dr. Wright and his assistant, Dr. Oscar Richardson, had conducted 4,200 autopsies. After the autopsy was completed, including associated microscopic and bacteriological evaluations, the bodies were brought to the hearse entrance attached to the Allen Street House.

Thus, the autopsy and Allen Street House became linked both physically and symbolically. When a patient at MGH passed away, their patient charts were stamped “Allen Street.” Physician and writer Lewis Thomas, while a student at HMS in the 1930s, wrote a poem titled “Allen Street,” that includes the telling lines:

But let us speak of Allen Street—that strangest, darkest turn,

Which squats behind a hospital, mysterious and stern.

It lies within a silent place, with open arms it waits

For patients who aren’t leaving through the customary gates.

It concentrates on end results, and caters to the guest

Who’s battled long with his disease, and come out second-best.

For in a well-run hospital, there’s no such thing as death.

There may be stoppage of the heart, and absence of the breath—

But no one dies!

No patient tries this disrespectful feat.

He simply sighs, rolls up his eyes, and goes to Allen Street.

Allen Street House was not only important for research but for teaching. Harvard Medical Students came to the House to observe autopsies and conduct laboratory work. The autopsy room was also a valuable resource for surgeons, who used the space to practice operative methods. By 1911, the amphitheater was outfitted for the projection of lantern slides, amplifying its didactic use. A few years later, in 1915, an animal house and experimental operating room were added next to Allen Street House to further expand its trial and teaching work.

Beginning in 1910, each Thursday at noon a clinicopathological conference was held in the Allen Street Amphitheater. If an autopsy was in progress when the clock struck noon, the body was quickly moved to the morgue to make space. These conferences were used as “case method” teaching tools for Harvard Medical School students and practicing physicians. During them, the case of a dead patient was presented and an expert was put in the spotlight. The expert, as if competing in a game show, would have to sort through the tangible facts and were challenged to put forward the correct diagnosis. The audience would question the “contestant’s” methods and, at the end, the proposed diagnosis was compared with the actual results of the patient’s autopsy.

By the mid-1940s, Allen Street House was again in need of major renovations. While blueprints were prepared in 1945, funding was scarce and the construction couldn’t occur. Part of the Allen Street complex, building number 57 and 58 were torn down in 1937 and number 56 and 59 were used for storage before being torn down around 1952. In 1956, MGH Pathology officially moved to the newly-constructed Warren building.

The Allen Street House was the beating heart of MGH’s Pathology Department from 1874 to 1956, overseeing the unit’s advent and expansion. While Allen Street House is gone physically, its memory and importance to the field of pathology persists today, and the euphemism “he went to Allen Street last night” (instead of “he died last night”) remains very much alive.

Article by Grace Clipson, edited by Bob Potenza.

Sources: Eugene J. Mark and Robert H. Young, “The Autopsy Service,” in Keen Minds to Explore the Dark Continents of Disease (2011); David N. Louis and Robert H. Young, “The Early Years (1811–1896),” in Keen Minds to Explore the Dark Continents of Disease (2011); David N. Louis and Robert H. Young, “The Mallory Era (1926–1951),” in Keen Minds to Explore the Dark Continents of Disease (2011); David N. Louis and Robert H. Young, “The Wright Era (1896–1926),” in Keen Minds to Explore the Dark Continents of Disease (2011); “The Passing of Allen Street,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 256, No. 6 (February 7, 1957); Sixty-First Annual Report of the Trustees of the Massachusetts General Hospital, 1874 (Boston: James F. Cotter & Co. Printers, 1875); Anita Slomski, “Case Records of the Massachusetts General Hospital,” Proto (March 29, 2022); Frederic Augustus Washburn, The Massachusetts General Hospital: Its Development, 1900-1935 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1939); Robert H. Young, “The 19th Century and the Era of Physician-Pathologists: The Warrens and Their Colleagues,” History of Pathology Society, 2015 Annual Meeting (Boston, MA).