After the First Mass: West Enders at St. Joseph’s Church

St. Joseph’s Church was established in 1862 on Chambers Street in the West End, near the site of the first public Catholic mass in Boston. In the early 1900s, the St. Joseph’s Association, an organization of parishioners, hosted an annual party at the church which also held many notable funerals, marriages, and worship services. Decades after urban renewal, West Enders reunited at annual masses at St. Joseph’s to honor deceased fellow residents.

On November 9, 1862, the Archdiocese of Boston dedicated St. Joseph’s Church on Chambers Street in the historic West End, following its purchase by Bishop John Bernard Fitzpatrick. Fitzpatrick had bought the church building (designed in 1834 by Alexander Parris, renowned architect of Quincy Market) from the Protestant Twelfth Congregational Society. The church’s location was the site of religious significance even before its dedication. In 1788, on nearby Green Street, French Catholics celebrated the first publicly-held Catholic mass in Boston. After the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 permitted Catholics to freely practice, first French and later Irish immigrants were key to the future growth of Catholicism in Massachusetts.

By 1912, on its 50th anniversary, St. Joseph’s Church boasted its peak membership of 12,000 parishioners. Ten years later, in 1922, city planners redesigned parts of Chambers Street and Green Street to create Cardinal O’Connell Way, named for Cardinal William O’Connell, who was assigned to St. Joseph’s in 1886 before rising through the ranks of the Archdiocese. St. Joseph’s Church, which resides on Cardinal O’Connell Way today, was significant for West Enders in the 20th century as a site of celebrations, remembrances, and reunions.

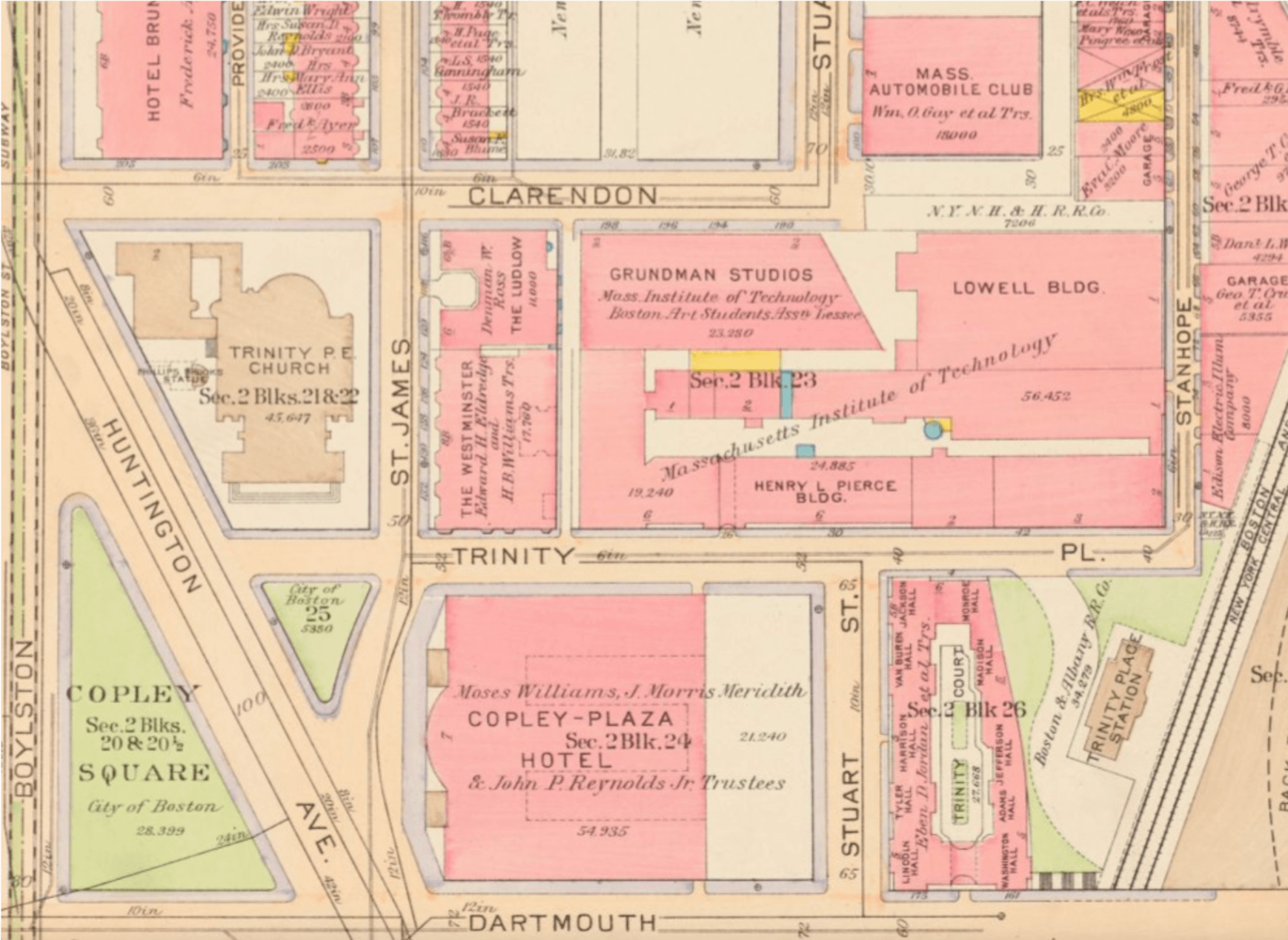

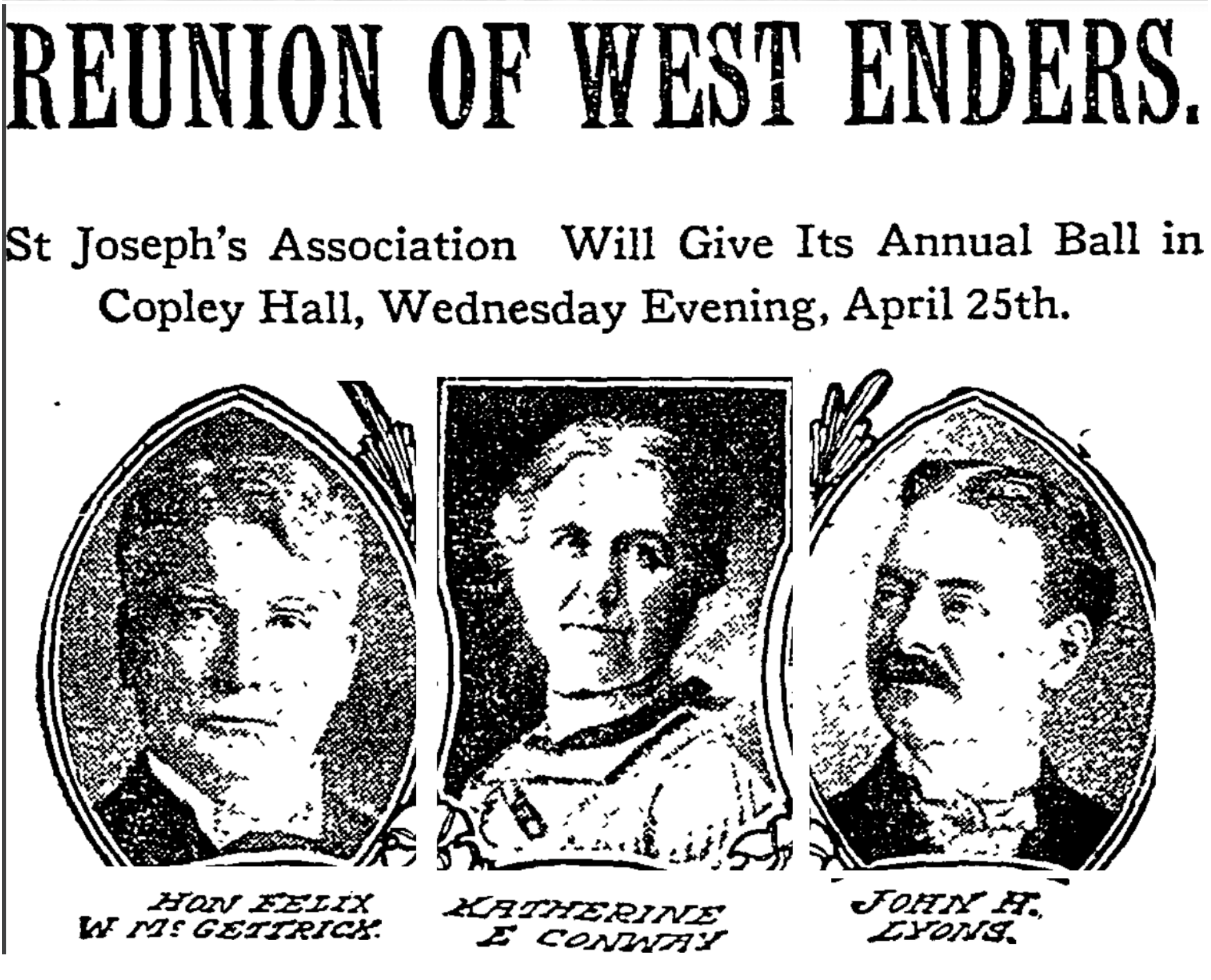

The St. Joseph’s Association, an organization of parishioners, made the church an important community space for Catholic West Enders in the early 1900s. Starting in 1902, the Association organized ten annual balls at Copley Hall, the multipurpose building built in 1893 on Clarendon Street in the Back Bay. In 1912, the ball moved to the St. Joseph’s Association Hall in the West End. Invitees over the years included politicians, clergy, school officials, police chiefs, athletic coaches, and heads of Catholic clubs. Guests at the 1906 ball included Katherine Conway, editor of the Pilot (the newspaper of the Archdiocese of Boston), John H. Lyons, a local real estate developer, and the Hon. Felix McGettrick, a federal immigration officer stationed in Vermont. Conway, the founder of Boston’s first Catholic reading group, strived to redefine traditional Catholic ideals that limited women to reproduction and housework. Her life and work was at odds with the positions of then-Archbishop William O’Connell, who railed against “sinister feminism.” McGettrick, from Boston, was known for discharging hundreds of Chinese immigrants arrested under the Chinese Exclusion Act, to the point that many had actively tried to appear before McGettrick (as the government gave extra attention to his cases).

Catholic women in the West End took the lead in organizing the balls, which featured formal attire, music, and dancing. The annual balls served not only as entertainment, but also as reunions for West Enders. According to the Boston Globe in 1912, the St. Joseph’s Association ball had “in the past…acted as the renewal of acquaintance of many of the old West Enders, who mingle and talk over old times.” The gathering was also known as “the year’s great social event of the ‘Old West End’,” as the Globe called it in 1907, because its participants largely came from an earlier generation of Irish immigrants.

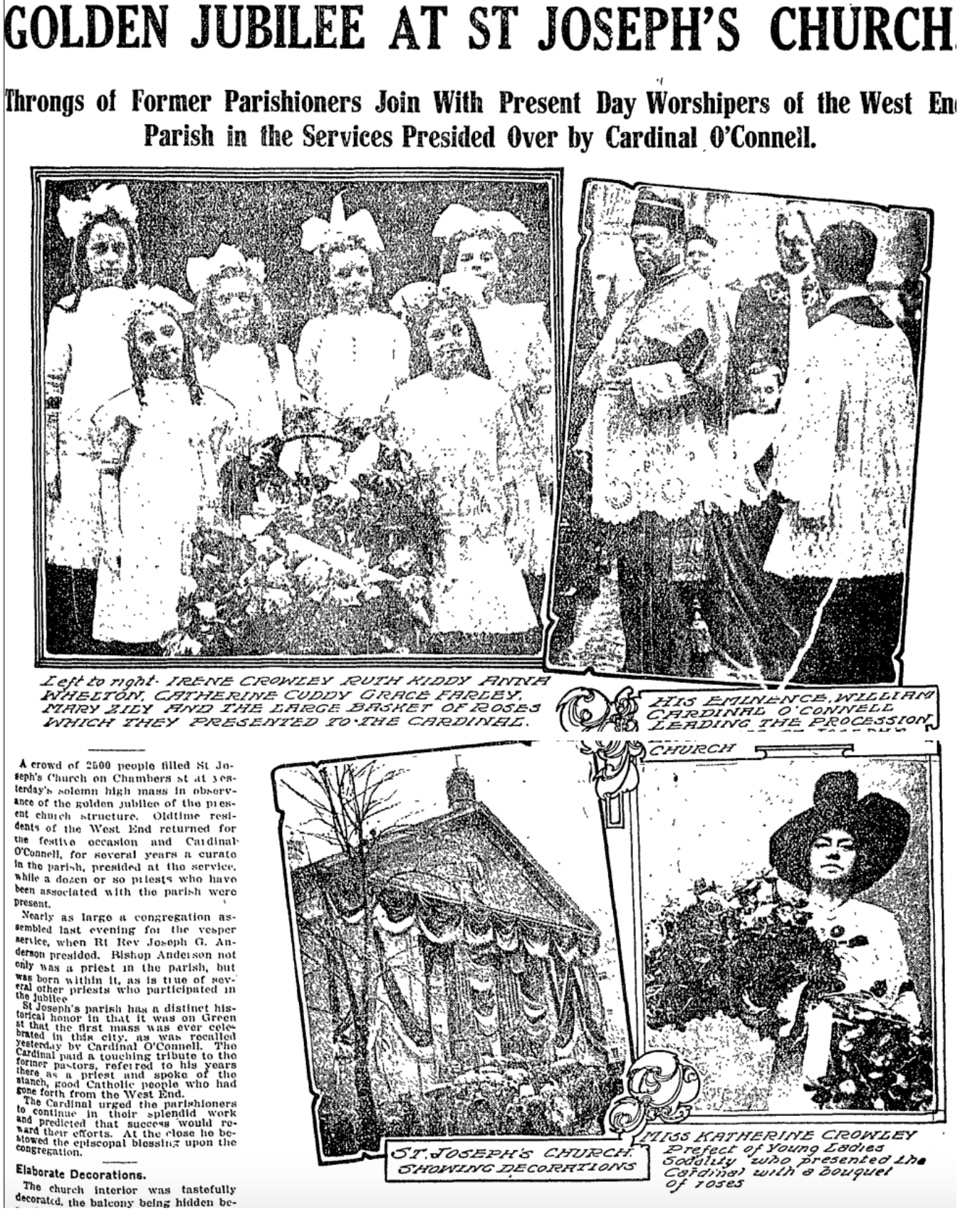

At the turn of the century, waves of Italian and Eastern European immigrants settled in the neighborhood and became the “new” West Enders. In November 1913, when St. Joseph’s celebrated its “Golden Jubilee,” or 50th anniversary, the church held ceremonies that reunited parishioners with its former priests, such as Cardinal O’Connell and Bishop Joseph Anderson, a native West Ender. Once an altar boy at the church, Anderson’s first mass as a reverend was held at St. Joseph’s after his ordination in 1892. The Globe shared the history of St. Joseph’s and its “illustrious sons” in a report on the Golden Jubilee. Because of the West End’s claim as host to the city’s first mass, its large population of Catholic immigrants, and the legacy of St. Joseph’s Church, the Globe declared in 1913 that “probably no section of the city is so rich in Catholic history as the West End.”

Decades after the urban renewal period, St. Joseph’s Church became an important site for reunions of West Enders in the 1990s and early 2000s. The March 2000 issue of Jim Campano’s West Ender Newsletter included photographs from a reunion of West Enders at St. Joseph’s, who gathered for an annual mass honoring those from the neighborhood who died. The West Enders’ mass was delayed by some months in 1999 after the passing of Rev. Gerald Bucke, the Irish-born pastor of St. Joseph’s since 1969. The gatherings of West Enders at the church, in recent decades, carried on the legacies of celebration, remembrance, and reunion that made St. Joseph’s, and the West End, vital to Boston’s Catholic history.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Sources: West End Museum; St. Joseph Boston; The West Ender (“St. Joseph’s Mass for Deceased West Enders,” March 2000); Boston Globe (“Patriotism of the Catholics,” October 25, 1908; “To Celebrate Golden Jubilee,” November 2, 1913; “Rev. Gerald Bucke,” April 17, 1999; “St Joseph’s Association Annual Ball, April 20, 1908; “Have ‘Family Party’,” November 29, 1912; “Prominent Men There,” April 26, 1906; “Reunion of West Enders,” April 22, 1906; “Miss Finnigan to Wed Athlete,” February 9, 1913); Paula Kane, “The Pulpit of the Hearthstone: Katherine Conway and Boston Catholic Women, 1900-1920,” U.S. Catholic Historian (1986)