Alonzo Meserve

Alonzo Meserve, principal of the Bowdoin School on Myrtle St. from 1886 to 1914, made significant contributions to Bowdoin’s student body and Boston’s ongoing struggle against racism.

Alonzo Meserve was born in North Abington on February 21, 1844. While attending public school, he worked for his father, a farmer and shoemaker, by making nine pairs of army shoes per day. When the Civil War broke out, Meserve was seventeen; he attempted to enlist in the Union Army but was denied because he was one year underage. After being denied enlistment, Meserve (still seventeen) had an “intellectual awakening”, and discovered his passion for education. He enrolled at his local high school at the age of eighteen, which his father accommodated by reducing his daily workload from nine pairs of shoes to seven. Meserve graduated from high school at the age of twenty-one, and started working as a substitute teacher and shoemaker until he graduated from the Bridgewater Normal School in 1868. He only paid partial tuition in exchange for working as manager of the school’s heating system.

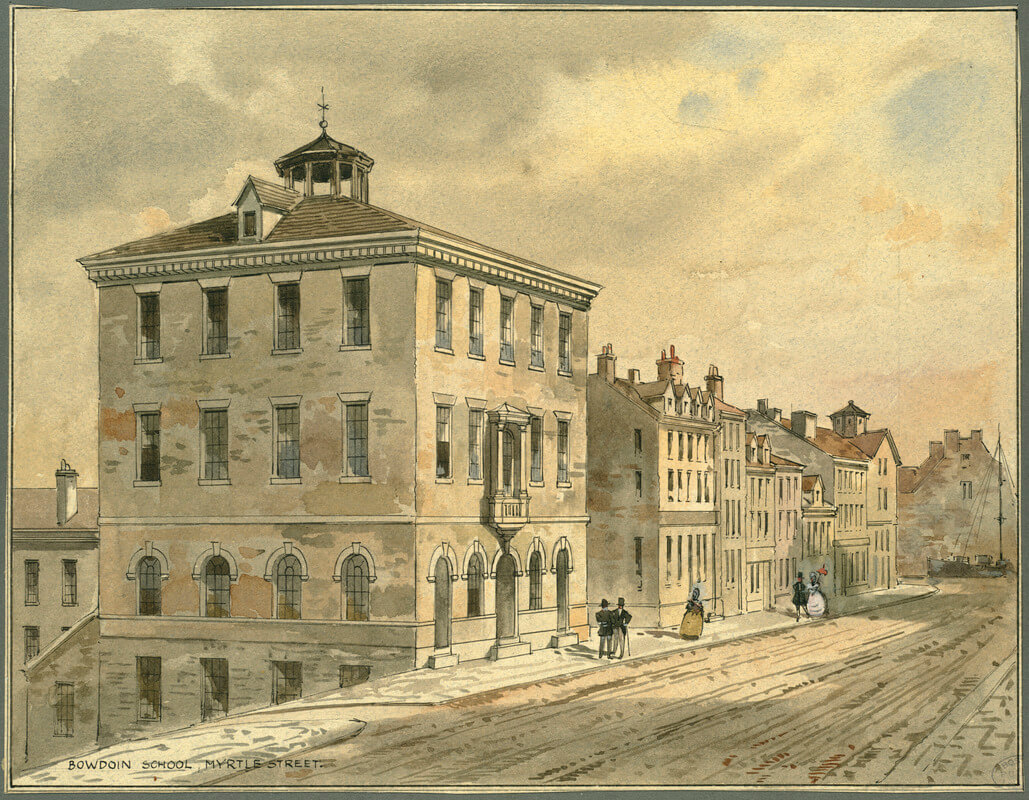

After graduating from the Bridgewater Normal School, Meserve became the principal of Whitman High School and Brockton High School. He taught at South Boston’s Bigelow School in 1871 and was hired three years later as “submaster” (assistant principal) at the Prescott School in Charlestown. In September 1886, Meserve became the “master” (principal) of the Bowdoin Grammar School for Girls, on Myrtle Street in the historic West End. While serving as master, Meserve continued to teach students, particularly ninth graders. In 1898, the Bowdoin School dedicated its new building on the same site as the old; the previous building stood on Myrtle Street since 1848. The new Bowdoin School was three stories high and built in sections, first the rear and then the front, so that students could be transferred to the new building while the old was torn down. The Bowdoin School stood on the site of abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner’s birthplace, and Meserve’s office was built in approximately the same area as the room where Sumner was born.

Meserve’s connection to the legacy of Charles Sumner was more than incidental. Some years later, on January 6, 1911, Meserve was invited to speak at the New England Suffrage League’s observance of the one-hundredth anniversary of Charles Sumner’s birth. Meserve previously attended the one-hundredth anniversary of William Lloyd Garrison’s birth, held at Faneuil Hall on December 11, 1905. Aside from attending ceremonies to the abolitionists of old, Meserve committed to tackling racial discrimination in contemporary Boston. On November 13, 1914, Meserve joined his peers on the Boston School Committee, including Joseph Lee, Jr., to unanimously vote for prohibiting a racist songbook from being distributed to students at the city’s public schools. The Committee discovered that schools had recently given students the “Forty Best Old Songs,” which contained songs with slurs including the n-word, “darky,” “massa,” and “missus.” The Boston School Committee heard from Francis J. Garrison, the last surviving son of William Lloyd Garrison, that singers throughout Boston, since before the Civil War, rightfully censored themselves when performing the songs under consideration (such as “Oh, Susanna!” and “Carry Me Back to Ol’ Virginny”) to avoid offending African-Americans. The Committee agreed with community leaders such as Rev. Montrose W. Thornton of the First A.M.E. Church that simply striking out the offensive language would be insufficient, and that the songbook should not be circulated among students of any race. Meserve and his peers agreed with Rev. Samuel Brown of St. Mark’s Congregational Church, that “These songs have no literary merit…The children can get enough poor English in the streets.”

By the time Meserve served on the Boston School Committee, he had already retired as master of the Bowdoin School. He retired in 1914, after twenty-eight years of service as principal, because of a School Committee rule that no one over seventy years old was allowed to continue teaching in public schools. In addition to his School Committee responsibilities, Meserve also served as president of the West End Parents’ Association. Leah L. Nichols-Wellington (Bowdoin Class of 1846), in her book History of the Bowdoin School, 1821-1907 (1912), commended Meserve for his exceptional teaching abilities despite the fact that he lacked a college education:

Although Mr. Meserve did not receive a college education, yet those who have watched and marked his work as master of the Bowdoin School, and seen its results, know that he is admirably adapted for carrying out what he chose for his life-work…Mr. Meserve, with his youthful determination and perseverance, working and studying, supplementing these in all his after years with constant and well selected self-instruction, may well be classed in his profession as a compeer with any college-educated instructor.

On December 11, 1916, Meserve died in his home on 87 Linden Street in Allston, at the age of seventy-three. He was buried in North Abington, where he was born.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Source: Internet Archive (“Manual of the public schools of the city of Boston” [1900], Leah L. Nichols-Wellington, History of the Bowdoin School, 1821-1907 [1912]), ProQuest (“Taught Nearly 50 Years,” Boston Globe, December 12, 1916, page 18; “Song Book Offensive to Afro-Americans Refused by Board,” The Chicago Defender, November 21, 1914, page 2; “Guest of Teachers,” Boston Globe, June 4, 1914, page 16; “Two Teachers to Be Retired,” Boston Globe, May 31, 1914; “Sumner Not Forgotten,” The Baltimore Afro-American, November 5, 1910, page 3; “Garrison’s Work As Yet Undone,” Boston Globe, December 12, 1905, page 16; “In Handsome New Quarters,” Boston Globe, June 3, 1898, page 6)