Boston College in the West End…Almost

The urban origins of Boston College trace back to its first home on Harrison Avenue in the South End of Boston, but if its founders had had their way, its birthplace would have been in the West End.

The founding of Boston College was part of a larger need for 19th century Boston Catholics to establish an educational system which would protect their children from the religious intolerance occurring at the time. The ten-year rise of the Irish Catholic population from relative insignificance to a position of numerical superiority by the mid-1850’s, inflamed the existing religious and social prejudice of the dominant Yankee population of the city. Incidents such as the burning of the Ursuline Academy in Charlestown (1834) and the Eliot School Controversy (1859) accelerated efforts by the Diocese of Boston to build more parochial schools for all ages in and around the city.

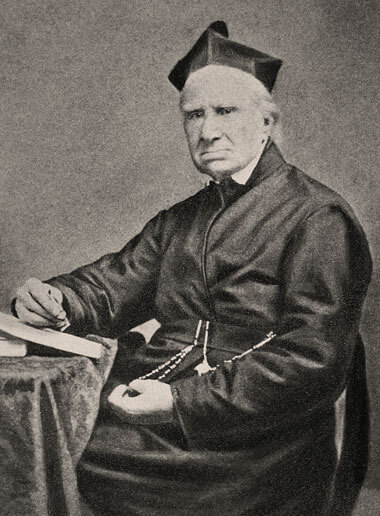

The man most credited with the founding of Boston College was John McElroy, a Northern Irish-born Jesuit who was transferred to Boston in 1847. Before arriving in Boston, he ran a parish, built Catholic schools around Baltimore, and served as one of the U.S. Army’s first Catholic chaplains during the Mexican-American War. McElroy was a close friend to Boston’s Bishop Benedict J. Fenwick, to whom he wrote in 1842 after a visit to Boston “no doubt in my mind, but your Cathedral and a splendid one, can be erected, in a few years and a College also, for the accommodation of 300 boys.” According to Catholic historians, this was the first written mention of building a Catholic college in Boston. The thought seemed to have taken hold, for when Boston’s new bishop, John B. Fitzpatrick, brought McElroy to Boston in 1847 to take over an insurgent parish (St. Marys of the North End), he remarked that it was “only the beginning of what I [Fitzpatrick] intend to do for the Society. The college is the main object of my concern; but I must wait for means.”

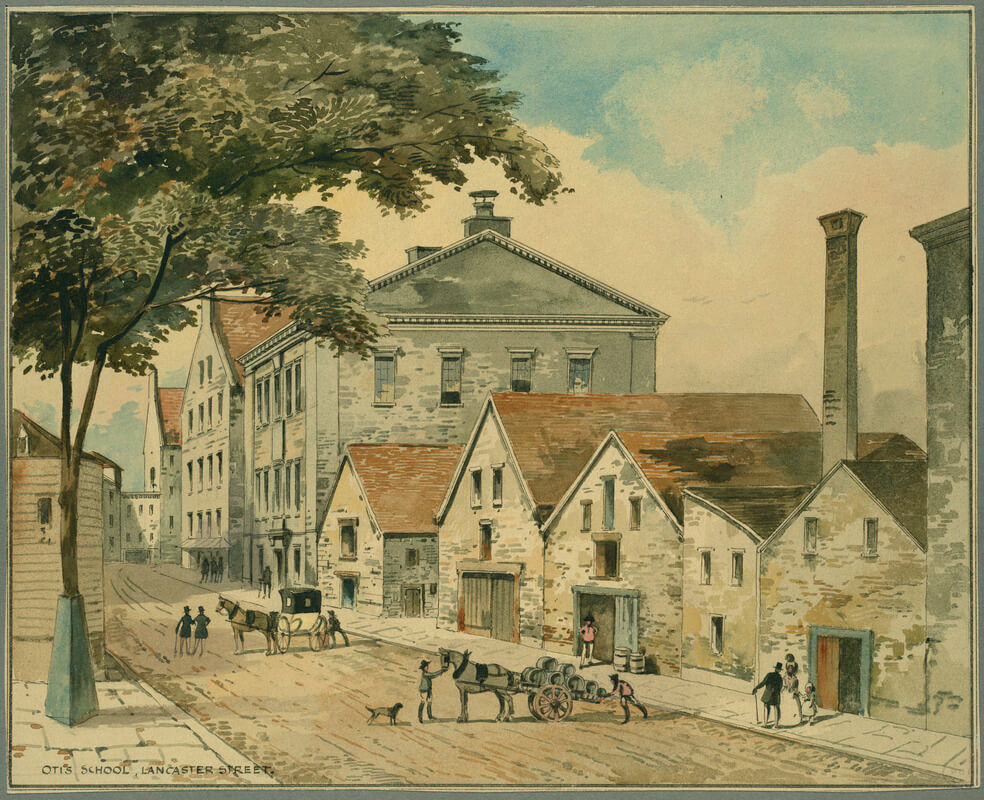

McElroy served for five years in Boston before he could make any concrete progress in creating a Catholic college. Finally, in 1852, Bishop Fitzpatrick authorized McElroy to buy the idle Otis School on Lancaster Street in the West End from the City of Boston for $16,500. There McElroy would create a day college for Catholic boys to “receive gratuitously or nearly so, a thorough education not only in the English branches but also in the languages, Philosophy &c.” This, however, was a short lived opportunity, as the Diocese soon decided instead to hand over the Otis School to the Sisters of Notre Dame as a new home for the St. Mary’s School for Girls, formerly located on Stillman Street.

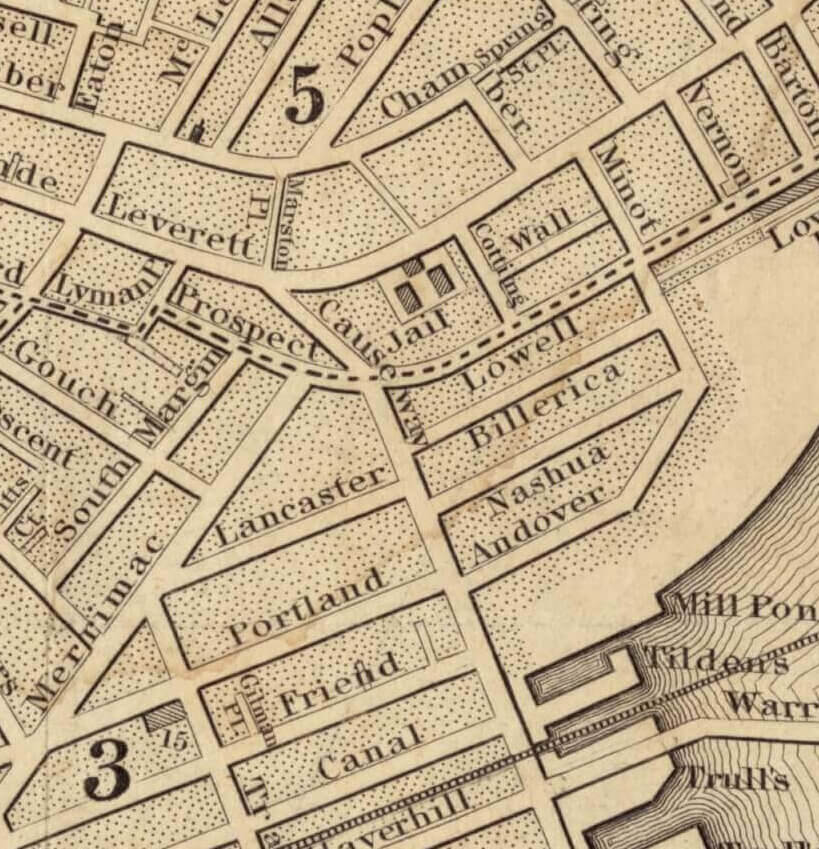

A year later, McElroy came upon another chance to build a new church and college, again in the West End. On December 3, 1851 the City of Boston announced its intent to auction off the land on which the City’s Leverett Street Jail had once stood (just behind today’s West End Museum). The lot was “bounded by Leverett and Causeway Streets on two sides; by property fronting on Lowell Street, on a third; and by other property fronting on Leverett, Wall, and Lowell Streets, on the fourth.” Colonel Josiah L. C. Amee bought the land and built ten housing units which he had trouble selling. Amee put the property up for sale in 1853, and the opportunistic Father McElroy was quick to purchase it for just under $60,000.”

McElroy and Bishop Fitzpatrick barely had time to celebrate before their plans were stymied by a group of 924 citizens, led by Nathaniel Hammond, who upon hearing that Catholics planned to build a church and school in their neighborhood, attempted to block the plans by petitioning the City to enforce prior restrictions on the property which limited its use to dwellings and stores. The City’s Committee on Public Lands ruled in favor of the petitioners, forcing the Diocese to appeal. Despite gaining the support of “twenty-five of the most prominent Protestant gentlemen in Boston”, including William Appleton, Abbot, Amos, and Samuel Lawrence, George Ticknor, and Edward Everett, the Catholics lost their case. McElroy and the church maintained ownership of the property for a while, collecting rents from the existing housing units, while continuing their fight to change the zoning restrictions. Having become weary of facing Know Nothing politicians and non-responsive administrations with no positive result, Bishop Fitzpatrick sold the Leverett Street lot in 1857, forcing McElroy to look elsewhere for a suitable site for his college. Before dismissing the West End entirely, McElroy investigated a neglected property on the corner of Spring and Milton Streets, but found it was unavailable.

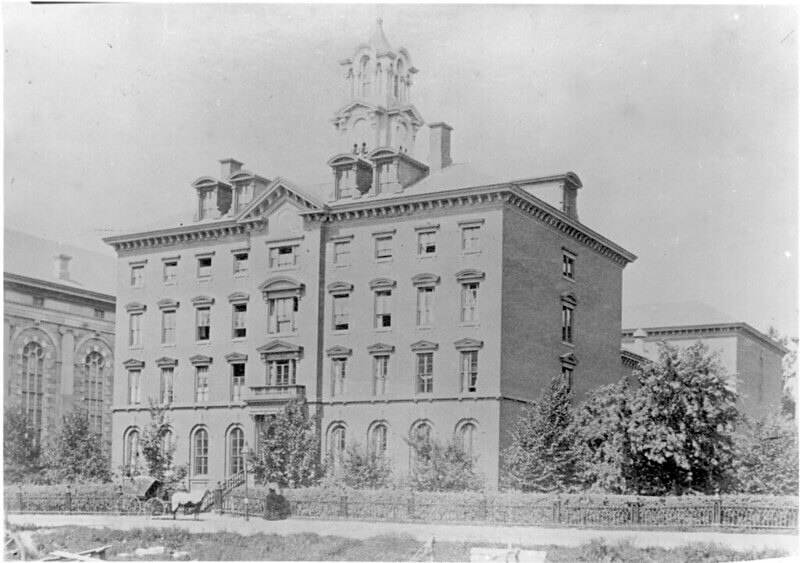

Soon after this last disappointment in the West End, McElroy and some Jesuit colleagues, while strolling through the “new” South End of Boston, decided that the neighborhood would be more suitable for a college “rather than the western section” of the city, because it was more convenient to other Catholic neighborhoods. Eventually, McElroy constructed the first home of Boston College, and Boston College High School, on Harrison Avenue, and in 1864 the college accepted its first class of 24 students. Fifty years later, in 1907, Boston College moved to its current home in Chestnut Hill, having outgrown its first urban home in the South…not the West…End.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Sources: DAVID R. DUNIGAN, S.J., Ph.D., ed. A HISTORY OF BOSTON COLLEGE. MILWAUKEE:THE BRUCE PUBLISHING COMPANY, 1947.; McElroy to Fenwick, Jan. 7, 1843, Diocesan Archives, Boston, Old Letters, “A,” No. IQ.; www.bc.edu; http://www.thebostonpilot.com/;Donovan, Charles F. (Charles Francis). 1984. Boston College’s First Boston Brahmin Friends. [Chestnut Hill, Mass. : Boston College]. http://archive.org/details/bostoncollegesfi00dono.;Donovan, Charles F. (Charles Francis), Paul A. FitzGerald, and David R. Dunigan. 1990. History of Boston College : From the Beginnings to 1990. Chestnut Hill, Mass. : University Press of Boston College. http://archive.org/details/historyofbostonc00dono.