Boston Marriages

At the turn of the century, “Boston marriages” enabled women to live independently from men. These relationships were common among educated female employees of settlement houses in Boston and in the greater United States. In the West End, evidence for these relationships can be found among the literary women of the period.

“Boston marriages” were one of the few ways for women to live independently from men in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The term was coined to describe a long-term, committed relationship between two unmarried women, involving anything from friendship to professional partnerships to lesbian romances. Regardless of the nature of the relationship, the significant factor of the Boston marriage was that it allowed women to assert their freedom and live without reliance on a father, brother, or, most importantly, husband. Some women who engaged in these relationships may have been married to a man at some point in their lives while others remained single throughout. Due to the secrecy and privacy of these women, it is often impossible to say whether there was a sexual component for every couple; therefore, it is vital to conceptualize them as queer, gender-nonconforming relationships without labels such as “lesbian” or “bisexual,” since the women would not have used those terms for themselves. That is not to say, however, that these relationships were all strictly chaste. Katharine Bement Davis conducted a study in the 1920s that surveyed educated middle-class women, and she found that out of 2,200 respondents who had attended college in the 1900s and 1910s, 50 percent reported having had “intense emotional relationships with other women” and 26 percent of these relationships were accompanied by overt sexual practices. Romantic same-sex relationships between women did exist, including in the West End, and should be discussed as such.

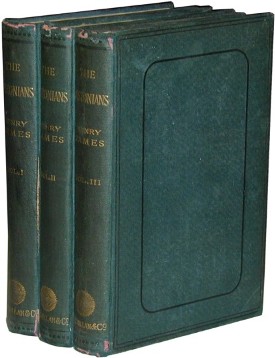

It is believed that Henry James’ 1885 novel The Bostonians may have inspired the phrase “Boston marriage.” The story features two women who form a deep attachment to one another until one of them is married off to a man. She gives up a loving relationship with another woman for the heteronormative stability of marriage to a man, even though she knows she is destined to be unhappy with him. Scholars such as Lillian Faderman have attempted to undo the popular ideas of twentieth-century sexologists about both this novel and the views of society as a whole—during this period, James would have had no prejudices against same-sex love and no reason to view love between women as an abnormality. The relationship that James portrays in The Bostonians may have been inspired by women James knew in real life, including his sister Alice James and her relationship with Katherine Loring, who was active in Boston charities.

Across the country, social work and settlement houses were closely tied with same-sex relationships between women. Jane Addams, the founder of Hull House in Chicago and the woman credited with bringing the settlement house movement to America, had two relationships with women in her life, first with Ellen Starr, who co-founded Hull House, and then with Mary Rozet Smith, a benefactor of Hull House. Even without these known romantic friendships, Addams and Hull House created a space where educated women could work and operate independently of their families and simultaneously help those in need, thus allowing them to exist outside of heteronormative expectations at the time. Social work opened a new avenue for women with professional aspirations. Addams also inspired an era when the wealthy began to think of the poor as their responsibility to aid rather than exploit. In Boston, there were also examples of Boston marriages among employees of the settlement houses. At Denison House in the South End, two couples formed from the group of founders: Vida Scudder and Florence Converse, and Katherine Coman and Katherine Lee Bates. In the North End, Edith Guerrier, who maintained a reading room and Boston Public Library station at a settlement house (and went on to be the first woman to lead a BPL branch library) had a Boston marriage with the artist Edith Brown. While no evidence has yet emerged about specific women associated with the West End settlement houses, it is certainly possible that these women, too, were engaging in fulfilling, romantic same-sex partnerships at this time.

One West End Boston marriage with ample evidence is the relationship between Sarah Orne Jewett (1848-1909) and Annie Adams Fields (1834-1915). Sarah Orne Jewett was born in South Berwick, Maine. Her father was a doctor, and she wanted to pursue this profession as well, but was unable due to multiple childhood illnesses. She had several same-sex romantic friendships in her youth, and her biographer (and distant relative) F. O. Matthiessen claims that she never had an interest in heterosexual love. She even told John Greenleaf Whittier that she was more in need of a wife than a husband, placing herself in the masculine role and indicating a desire to partner up with someone who could fulfill the duties traditionally performed by a wife. Jewett began submitting stories to serial publications in 1868 when she was eighteen years old. Her second story was sent to the Atlantic Monthly, where James T. Fields was editor. It was rejected but came back with an encouraging letter from the editors, likely her first interaction with the Fields couple. Eventually, the Atlantic published her Maine stories, which were collected in the book Deephaven, published in 1877. These stories featured relationships between women in a fictional town in rural, seaside Maine. The relationships were accepted by the townsfolk, because intimate relationships between women were not pathologized as “inverted.” Deephaven was rereleased in an illustrated edition in 1893, and Jewett worked with the artists to consciously create images that hinted at the intimate same-sex relationships of the characters.

Annie Adams Fields was also a prolific writer, though she is not well-remembered for it today. She was mainly known for her memoirs and biographies of contemporary famous writers. In 1854, she married James T. Fields, of the publishing house Ticknor & Fields. They entertained many famous authors, artists, and personalities of the time, such as Longfellow, Emerson, Hawthorne, Lowell, and Holmes, at their home at 148 Charles Street in the historic West End, and their marriage was a happy one. James T. Fields died in 1881, and there is speculation that he may have encouraged his wife’s relationship with Jewett even before his passing. As early as 1880, Jewett addressed poems to Fields about women exchanging rings as anniversary gifts:

Did I think of the wretched mornings

When I should kiss my ring

And long with all my heart to see

The girl who gave the ring to me.

Not long after James T. Fields’ passing, Jewett came to stay with Annie at her marital home. Together, they were involved in charity work in the city and spent time away writing—free from distraction because Fields had no children. They traveled to Europe together in 1882. They had many things in common and already shared a close friendship before Fields’ husband’s death, so they were able to continue their deep companionship for the rest of their lives. Jewett suffered a stroke in March 1909 in the Charles Street house and requested to return home to South Berwick, where she died on June 24 of the same year. Fields died in 1915.

In the early twentieth century, the cultural view of same-sex relationships changed significantly, causing them to be viewed as unnatural and wrong and often erased from biographies of women like Sarah Orne Jewett and Annie Adams Fields. These women also deeply valued their privacy, meaning that they made choices about what kinds of evidence they would leave for future generations to discover, especially when we speak of women who were not well-known or famous in their own right. Jewett and Fields are an example of the types of relationships that existed outside of the heteronormative paradigm in the historic West End.

Article by Emma Beckman, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Sarah Deutsch, Women and the City: Gender, Space, and Power in Boston, 1870-1940 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Lillian Faderman, Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love between Women from the Renaissance to the Present (New York: Morrow, 1981); Lillian Faderman, To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999); Carol L. Nigro, “Annie Adams Fields: Female Voice in a Male Chorus,” Ph.D. Dissertation, Georgia State University, 1996; Wendy L. Rouse, Public Faces, Secret Lives: A Queer History of the Women’s Suffrage Movement (NYU Press, 2022); Adam Sonstegard, “‘Bedtime’ for a Boston Marriage: Sarah Orne Jewett’s Illustrated Deephaven,” The New England Quarterly 92, no. 1 (2019): 75–10; Margaret Farrand Thorp, Sarah Orne Jewett – American Writers 61: University of Minnesota Pamphlets on American Writers, NED-New edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1966).

1 Comment