Chemical Man & the 1939 World’s Fair

At New York’s 1939-40 World’s Fair, a young man from the West End presented the Chemical Man, a working model of the human digestive system.

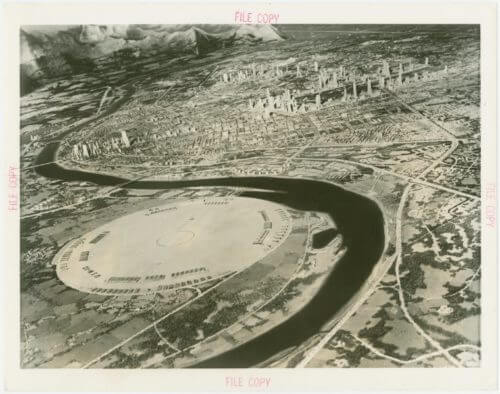

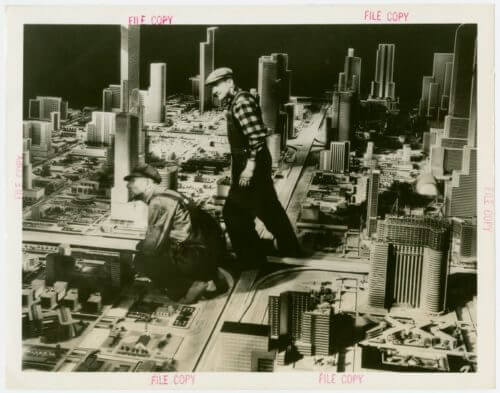

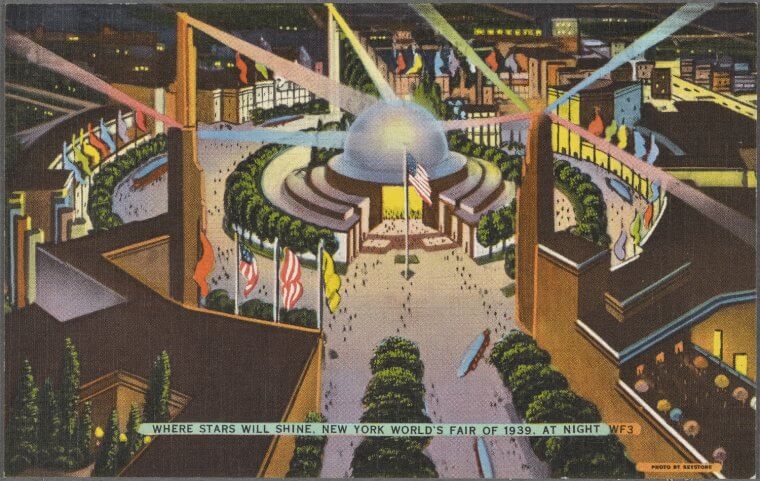

The 1939-1940 World’s Fair drew more than 44 million eager spectators to Flushing Meadows in Queens, New York over the course of its two seasons. The attractions took the fair’s theme of “The World of Tomorrow” to great heights by showcasing a myriad of remarkable advancements and visions of the future. Reports at the time widely acknowledged General Motors’ “Futurama” as the fair’s most popular attraction. The ride, designed by Norman Bel Geddes, trekked passengers around in chairs on a conveyor system to view an enormous model representing America in 1960. Billy Rose’s “Aquacade,” which featured a synchronized swimming show starring former Olympic gold medalists Eleanor Holm and Johnny “Tarzan” Weismuller, also wowed the crowds.

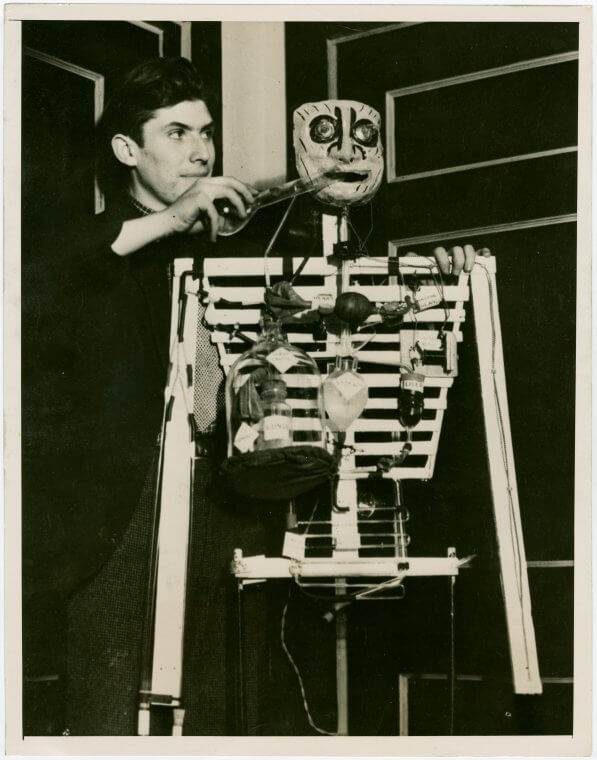

Among hundreds of influential creations produced by big-name companies worldwide stood the work of 16-year-old Hyman Gordon from the West End of Boston. Gordon’s science project, called “Chemical Man,” demonstrated the human digestive system in a very innovative way.

Gordon drew inspiration as a member of the science club at the West End’s Elizabeth Peabody House. Established in 1896, the settlement house focused largely on children’s issues and education, but also uplifted and educated the adult immigrants in the community. When a program initiated by the American Institute of New York to bring science club members to the 1939 World’s Fair, the Peabody House group took part. The Institute had begun running children’s science fairs more than a decade earlier as part of its mission to strengthen science education in the United States. In 1938, the organization convinced Westinghouse Electric & Manufacturing Company to donate space and equipment in its building at the World’s Fair to showcase award-winning exhibits from the Institute’s annual Junior Science Fair. In the 1939 season of the fair, 825 students presented projects on a range of science fields. Due to its location, it is not surprising that most came from New York; the Peabody House science club represented one of the few out-of-town groups.

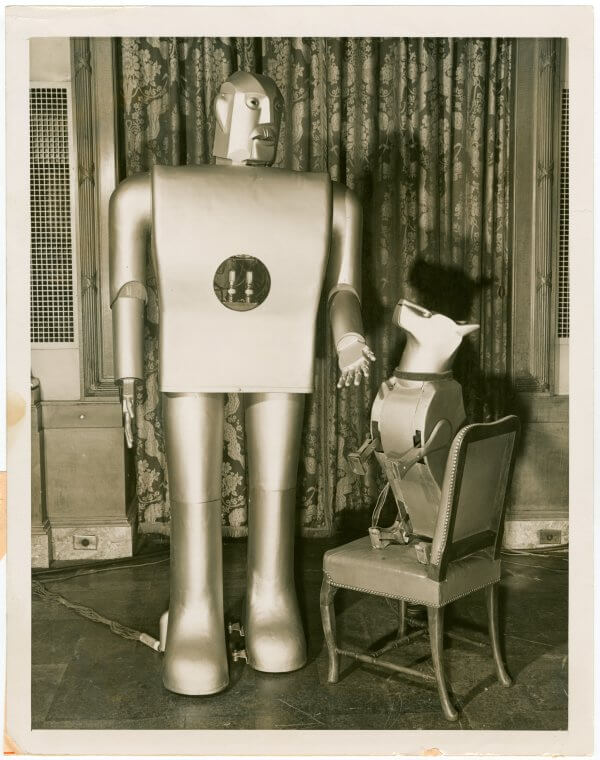

Student’s projects stood in the Westinghouse building along with other important exhibit items like the Westinghouse Time Capsule (to be opened 5,000 years in the future) and an early robot called Elektro. One of just 40 projects on display in the Junior Science Hall, Gordon’s Chemical Man had a face like a mask with a wide mouth on top of a skeletal frame featuring bottles and beakers labeled for the stomach and liver and thin, winding tubes labeled for the small and large intestines.

Gordon’s Chemical Man may look a bit unwieldy compared to modern models of the digestive system, but it was extremely inventive for its time. It showed World’s Fair visitors the internal process of how the digestive system worked in the least sickening manner possible. A lot of what is known about the digestive system at the time came from groundbreaking experiments conducted by U.S. Army doctor William Beaumont on Alexis St. Martin between 1822 and 1833. St. Martin had suffered a gunshot wound that never healed completely, leaving a hole through which his digestive system could be observed. Hyman Gordon’s model allowed people to experience the same scientific phenomenon in a far more ethical and sanitary way.

Gordon’s and other student’s projects boosted the growth of science education in America and the World’s Fair itself. The fair provided the American people some relief and distraction from the Great Depression, and the focus on future technologies helped prepare the next generation of young scientists for the challenges to come. By the end of 1939, the American Institute added 800 new science clubs to its roster, more than tripling its membership from 6,000 to 18,500 students.

While Gordon’s project was small on its own, the work of this teenager from the West End contributed to a movement of student work that helped prepare a generation of U.S. scientists. Their work led the nation through the Cold War, the Space Race and a half-century of immense progress in science and engineering.

Article by Angelica Dilorio, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Source: Price, (2018 August 13) Probing the Mysteries of Human Digestion. Science History Institute; Rydell, R. W., Findling, J. E., Pelle, K. (2000). Fair America: World’s Fairs in the United States. Smithsonian Institution Press; Terzian, S. G. (2009). The 1939–1940 New York World’s Fair and the transformation of the American science extracurriculum. Science Education, 93(5), 892-914; Wruts, R. (1977) The New York World’s Fair 1939-1940. Dover Publications