Dr. Charles Wilinsky and the West End’s First Health Center

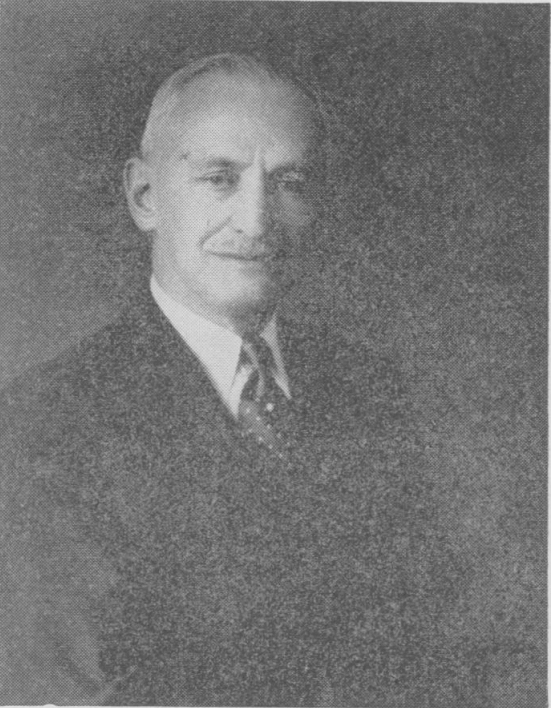

Dr. Charles Wilinsky, a Polish immigrant who cared for West Enders at his private medical practice, founded the neighborhood’s first dedicated health center to centralize disparate healthcare services and educate West Enders in preventative healthcare practices.

The first dedicated health unit established in the City of Boston opened its doors in 1916 at the Municipal Building on 17 Blossom Street in the West End. The purpose of the health unit, operated by the Boston Health Department, was to offer exhibits, resources, and on-call inspectors to encourage West Enders to participate in preserving and improving their own health. The West End’s health unit was the product of efforts by Dr. Charles F. Wilinsky, in collaboration with city government. Born in Warsaw, Poland, and the son of a doctor, Wilinsky immigrated to Massachusetts with his parents in 1892. After receiving his medical degree in Baltimore, Wilinsky and his wife moved to the West End in 1904, and at twenty-one years of age he started his private medical practice on Green St. Wilinsky saw that West Enders, many of whom were poor immigrants, desperately needed greater access to healthcare. He met with Mayor James Michael Curley in 1915 to advocate for “some sort of pioneer health center” in the neighborhood. There were already disparate agencies, public and private, trying to serve the health needs of West Enders, but Dr. Wilinsky believed that their efforts could be more effective if they were centralized in health centers.

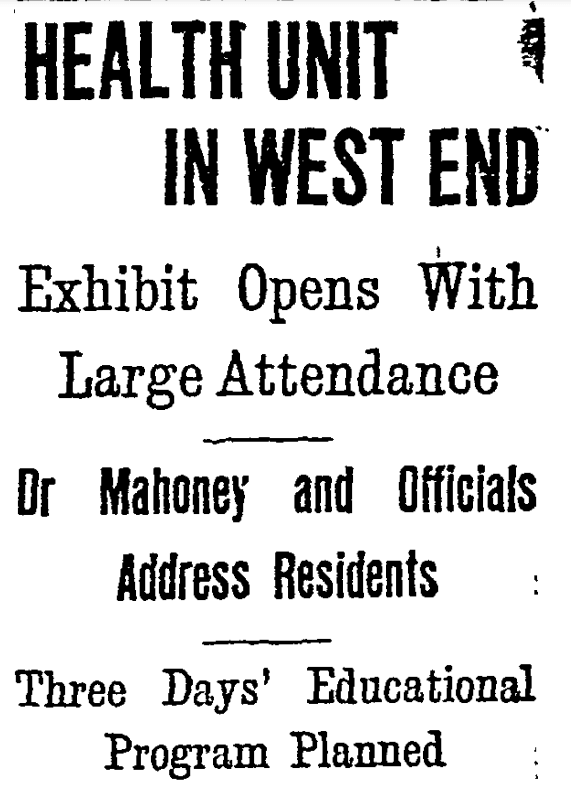

Mayor Curley agreed with Dr. Wilinsky’s proposal and granted the Doctor use of the Municipal Building on 17 Blossom St. to start the health unit, thus transferring ownership of the building from the Park and Recreation Department to the Health Department. This change in building usage was initially opposed by the West End’s young basketball players, who lamented that they could no longer “use the building as an arena for their games and for baths.” But when the West End’s health unit opened in late March 1916, 1,000 “enthusiastic residents” of the West End, mainly women, attended a three-day health exhibit. The exhibit’s focus was on the resources of the new health unit and preventative medicine, and included addresses from speakers like Dr. Charles Wilinsky, Boston’s Health Commissioner, and Samuel Schmidt, manager of the Wells School Center, who spoke in English and Yiddish.

The health unit would include on-call investigators for complaints about food and sanitation, two visiting nurses and a city physician, free vaccination clinics, and representatives from charities, thus achieving Dr. Wilinsky’s goal of centralizing public and private health agencies’ work. Organizations that staffed tables at the three-day opening exhibit included the Health Department’s various divisions, as well as the Women’s Municipal League, the Boston Association for the Relief and Control of Tuberculosis, and the Milk and Baby Hygiene Association. From the Boston Globe’s perspective, the apparent enthusiasm from residents indicated that “the opposition of the West End youth to the establishment of a health unit in that district – the first in the city – is practically overcome.”

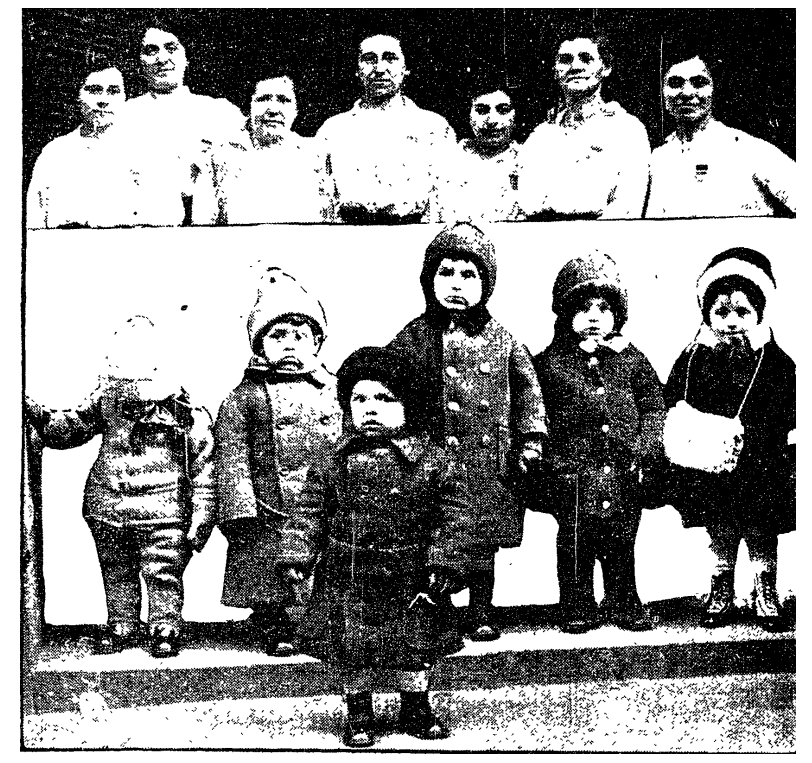

During Mayor Curley’s tenure, City Hall took over Boston’s baby clinics and put Dr. Wilinsky in charge of them in an effort to more strongly prioritize infant health and wellness. In the spirit of this initiative, the West End’s health unit had, since 1916, hosted a very popular competition, the “baby show.” This competition, organized by the Ladies’ Auxiliary of the Working Men’s Circle of Boston in order to promote child welfare, had West Enders entering their young children for a health examination by three doctors. The baby shows had two sections, one for children under two years old and another for children between two and five, with separate prizes for boys and girls in each category. The healthiest and most beautiful children – groomed by their parents in preparation – received awards that were announced at the Elizabeth Peabody House at 357 Charles Street. The prizes for children ages 2-5 were a sweater for boys, and a set of silver utensils for girls. The Globe reported on December 31, 1916 that the previous day, the competition saw “babies large and babies small, babies of all complexions and with parents of a dozen nationalities…more babies than one would have thought could be found in the whole West End.” Dr. Wilinsky told the parents assembled at the January 1917 baby show that although the prizes could only be awarded to a few babies, “every one of them ought to have a prize” in his estimation. The mothers in attendance were given booklets about maintaining their children’s’ health, and heard speeches about the same topic.

In 1929, the West End’s health unit moved from 17 Blossom St. to a new building at the corner of Blossom and Parkman St., owing to financial support from the George Robert White Fund. White, a philanthropist who made his fortune in “Jamaica ginger, Cuticura soap and Boston real estate.” Upon his death in 1922, he left all of his properties to the City of Boston, requiring that the “net income” they generated would be strictly devoted to local projects for the public good. On December 27, 1929, Boston officials laid the cornerstone of the building that would become the new health unit in the West End. At the cornerstone ceremony, speakers included White Fund manager George Phelan, Mayor Malcolm Nichols, and Health Commissioner Dr. Francis X. “F.X.” Mahoney.

The new health unit would cost $322,000, have four stories, and be “60 by 108 feet, with light and air on three sides.” The Globe reported that “residents of the district of many races and creeds attended the laying of the cornerstone,” and the appreciation felt by West Enders was echoed by the district’s City Councilor, John I. Fitzgerald. Mayor Nichols spoke about how the West End’s health unit saw doctors from all over the world visit to witness the benefits of health units for local communities.

The West End’s health unit was the sixth of its kind supported by the White Fund; other units included one in the North End (1924), and another on Whittier St., Roxbury (1932). By 1948, Dr. Wilinsky had become president of the American Public Health Association, after previously being appointed executive director of Beth Israel Hospital. In 1953, Dr. Wilinsky gave up his directorship of Beth Israel, and his official connection to the Boston City Health Department, in preparation for retirement. Wilinsky moved to Brighton after his wife died, and later to Brookline, where he died in 1970 at the age of 87.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Bob Potenza

Source: City of Boston (for George Robert White Fund); The Jewish Times; ProQuest/Boston Globe