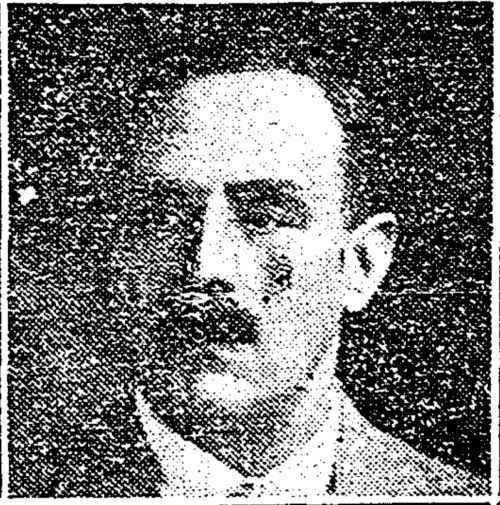

Harry E. Burroughs and the Burroughs Newsboys

Hundreds of boys from the West End and other parts of Boston benefited from the financial, education, and moral support provided by the Burroughs Newsboys Foundation.

The Burroughs Newsboy Foundation was the brainchild of Boston lawyer and philanthropist, Harry E. Burroughs. Burroughs designed the Foundation along the lines of a settlement house, focused on providing the city’s 4000 young newsboys and other street vendors with the opportunity to develop basic practical skills (e.g. trade skills, financial management, civic studies), as well as health, education, and recreational support. The organization’s motto was “To strive, study, and save.”

Burroughs’ inspiration for the foundation came from his own plight of being a working class boy forced to support himself in the streets of Europe and the United States. Born in 1890 in Poland (then part of the Russian Empire) and orphaned at the age of twelve, Burroughs survived by selling newspapers on the streets of Russia. After receiving permission from the Czar to emigrate, he landed first in Germany, then England, and finally in Portland, Maine. The rest of Burroughs’ story reads like a fairy tale. He walked from Maine to Boston and sold newspapers until receiving a four-year scholarship to Suffolk Law School. He served in WWI, and established a successful law practice where he earned over $100,000 a year “doctoring sick businesses”.

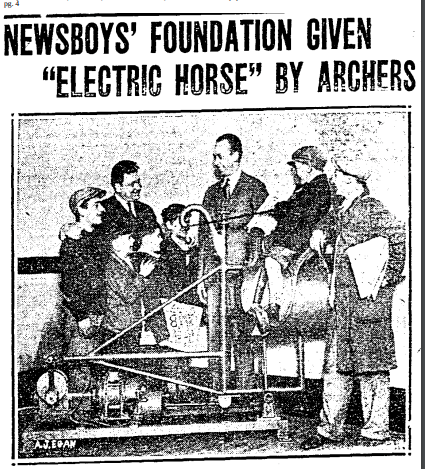

In 1928, he described his vision for the Foundation to the Massachusetts Public Welfare Board as “a ‘factory’ to train these youngsters to become real citizens”, For him, this was a symbolic way of repaying his adopted city and those who gave him the opportunity to succeed. He purchased the former headquarters of the Boston Elks at 10 Somerset Street $200,000 as the site for his foundation. There he created a sanctuary for these boys where they could study, receive medical attention, watch movies, and even play on a $1000 “Electric horse”, identical to that used by then President Calvin Coolidge in the White House, which was donated to the club.

Burroughs encouraged the Newsboys to participate in the executive and legislative operation of the club, including an annual election of a “Mayor of Newsboyville.” A coveted achievement, won more than once by West Enders, Boston newspapers often covered the election results. The Newsboys also promoted causes throughout the existence of the club, such as protesting against the dangers of endurance boxing matches, and opposing plans to raise the minimum age of newsboys to seventeen. They also supported the war effort during WWII by constructing airplane models for the Navy, training in junior air raid and fire warden work, and printing for the Committee on Public Safety and the Selective Service Board.

The health of these young men, who were often from poor families, was of supreme importance to Burroughs, who himself still felt debilitating effects on his body from the strains of carrying heavy loads of newspapers. He recruited the renowned German expert in “corrective gymnastics”, Harvard’s Hans Neudorf, to instruct the boys properly handling their daily loads without injury. Burrough’s also provided regular medical and dental services at the Foundation, the success of which was demonstrated when 96.3 percent of the boys called for duty during WWII were found physically fit for Army or Navy service, compared to the country’s 50 percent average.

To further encourage healthy living, Burroughs early on arranged outings for the boys, such as a trip to Gloucester where the Foundation’s orchestral group toured the town, recreated by the ocean, and later played a concert for ailing residents. Later in 1935, Burroughs opened Camp Agassiz in Poland, ME, named after philanthropist Maximillian Agassiz, who provided the remaining funds needed to open the camp. For fifteen years the camp not only exposed the Newsboys, and other boys working in the street trades to country living, but also taught them basic living skills, leadership and civic duties, and of course provided physical recreation. As at the Foundation, the boys governed themselves at Camp Agassiz in the style of a New England Town government.

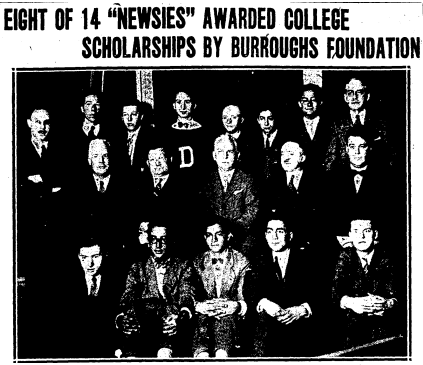

Perhaps the most important benefit offered to the Burroughs Newsboys was the annual awarding of college scholarships. The Foundation awarded the first five $200 scholarships in June of 1928, and eight more that August. Winners planned to attend Boston University, Northeastern University, M.I.T., Harvard, and Dartmouth. The awarding of such scholarships continued throughout the Foundations existence and were, again, representative of the kind of opportunity Burroughs himself benefited from as a youth in need.

Harry E. Burroughs died of cancer in the Beth Israel Hospital in 1946. His wife Hannah was elected by the Foundation’s board as his successor as director, but unfortunately the Burrough’s Newsboys would soon be forced to close. In 1950, United Community Services, the parent organization of the Foundation, decided to cut funding of the Burroughs Newsboys, citing that it no longer supported a “specialized group” (street traders), and that its location on Beacon Hill was too distant to support its majority of members from the North End and West End. The Foundation was forced to close its Somerset Street location in 1951. Today the former site of the Burroughs Newsboys Foundation is occupied by a Suffolk University housing complex, built by a former Burroughs Newsboy, Nathan R. MIller.

Thanks to the vision of Harry E. Burroughs and the immense gratitude he felt for the compassion others showed to him, thousands of underprivileged boys had a chance to realize their full potential through care, training, and financial support. At a minimum, those who participated in its activities found some kindness and comfort after a hard day of working in the streets of Boston. Camp Agassiz, now named Agassiz Village, still operates as a rural retreat for young children from diverse backgrounds, providing inspiration for campers to find their full potential.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Sources: agassizvillage.org, Boston Globe, The West Ender Newsletter

2 Comments