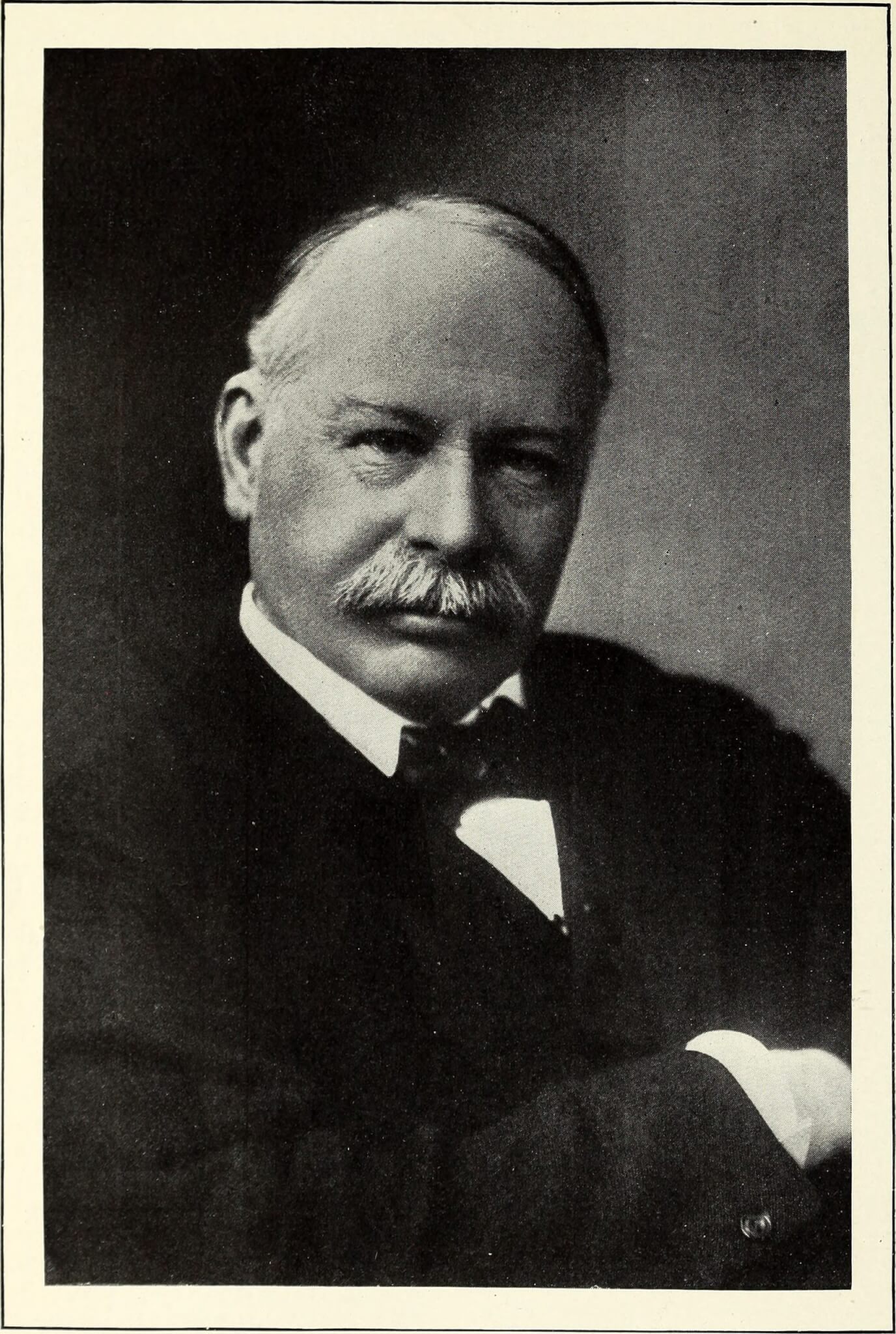

Henry Whitney

Henry Whitney was the president and founder of the West End Street Railway Company during the Gilded Age. He led the company to expand across Boston, and was integral to Boston completing North America’s first subway lines, the precursor to today’s MBTA.

Henry Melville Whitney was born on October 22, 1839 in Conway, Massachusetts to James Scollay Whitney and Laurinda Collins. Henry was the second of seven children and lived in affluent circumstances. He grew up with hearing issues, and was nearly deaf for his entire life. Henry’s father, James, was the president of the Metropolitan Steamship Company, and at one point lived in Coolidge Corner. Both Henry and his brother, William Collins, graduated from the Williston Seminary in Easthampton, MA in 1859. Henry then explored a number of ventures, and would go on to secretarial positions, speculating on cotton, and attempting business schemes around lifting sunken ships during the Civil War. By 1866 Whitney was an agent for his father’s steamship company and became its president in 1878 when James died. As a speculator, Henry Whitney bought up land along Beacon St. along with other Brookline real estate, having invested $800,000 by 1886. These investments caused Whitney to over-extended himself, and led him to connect with wealthy friends to form the West End Land Company that year. Whitney also founded the West End Street Railway Company – owing it’s name to the Land Company – and purchased a large financial stake in each of the five street railway systems in the city. The Street Railway Committee of Massachusetts was strongly opposed to Whitney’s attempt at consolidation, but he convinced the legislators that an integrated system run by one company would be preferable.

In 1887, Whitney purchased the 200 feet of land necessary for his proposal to the Board of Selectmen to widen Commonwealth Avenue. The West End Street Railway Company hired Frederick Law Olmsted and John C. Olmsted for this project, which would have had bridle paths, a commercial lane, a “pleasure drive,” and a lane for walking, biking, and streetcar tracks all separated by trees. Earlier Whitney proposed a subway tunnel under Boston Common. Because many ordinary people in Boston were critical of the project for potentially being too expensive, Whitney spoke to a town hearing in late January 1887 and argued that “The only objection that any citizen can make to Commonwealth Avenue is, that it is a place that only the rich can enjoy…There are hundreds and thousands of men who will dwell within this region within the next thirty years, whether this avenue is built or not, whom the ability to ride back and forth over an avenue of this kind will be a blessing, the value of which it is impossible to overestimate. It will to the laboring man, the mechanic, the clerk, and to the poor woman, the only opportunity which they may have of looking upon a green tree or green grass from one year’s end to the other.” Many ordinary Bostonians were not convinced that Whitney’s altruistic self-image matched the ‘robber baron’-like activity of someone engaged in corporate consolidation, but the city still approved his Commonwealth Avenue project at a reduced scale, extended by 160 feet instead of 200.

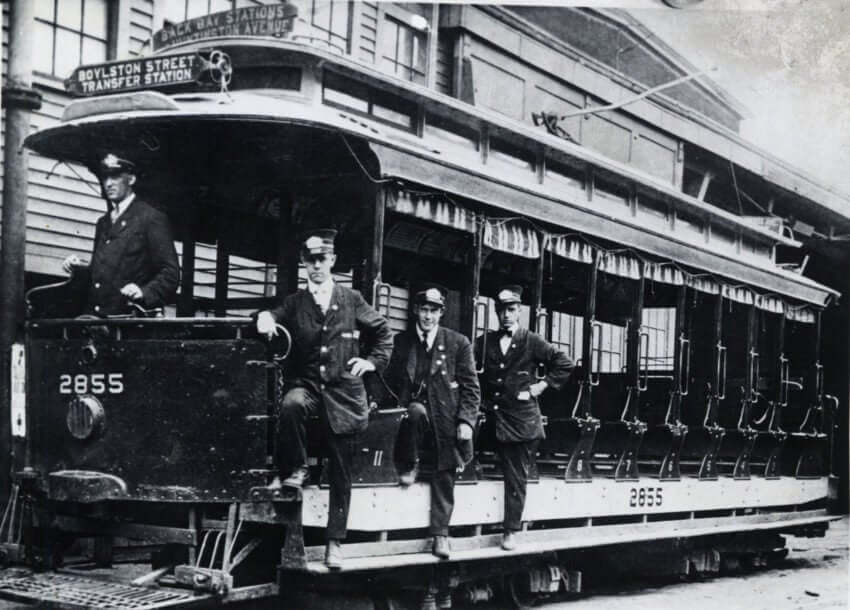

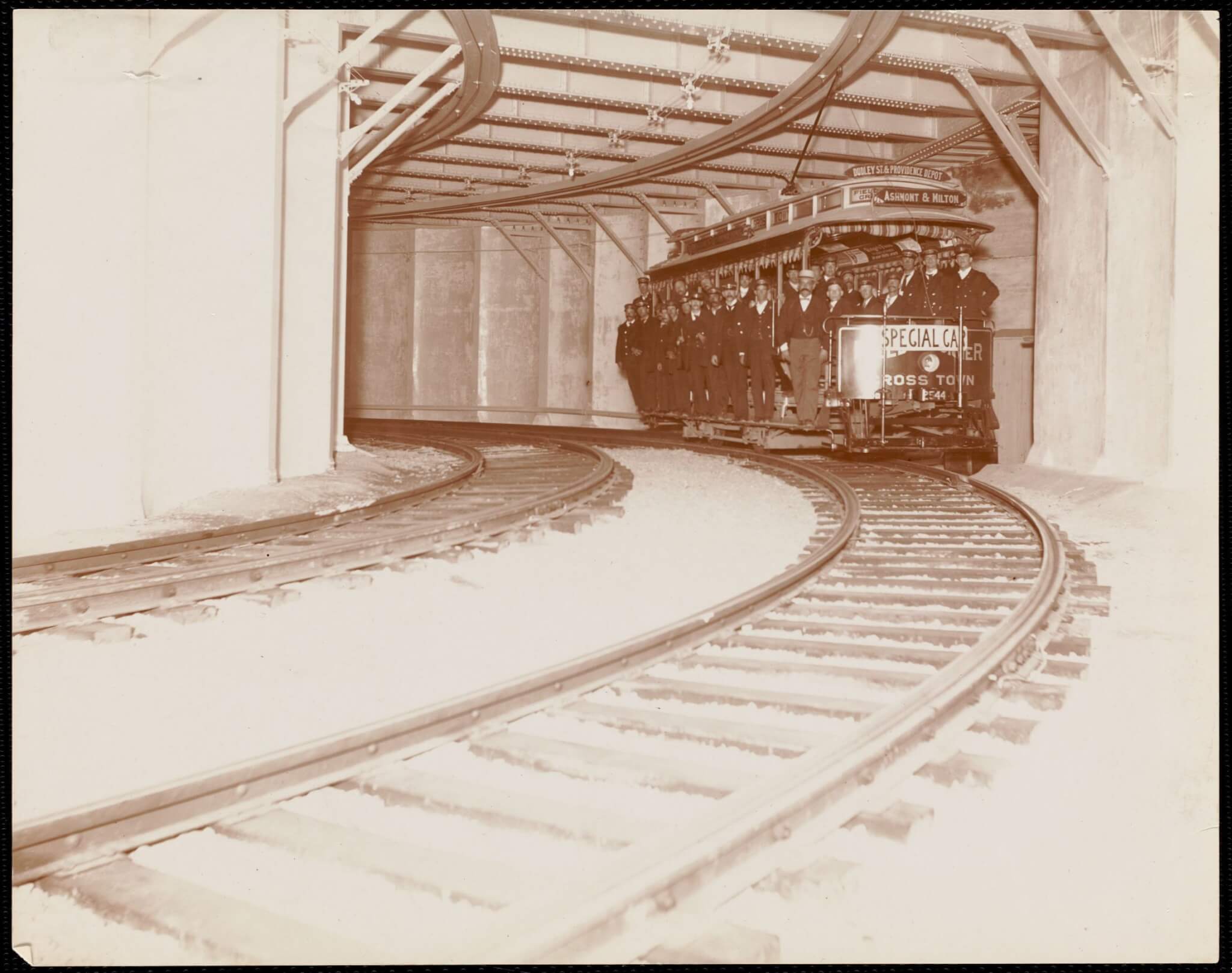

By April 1887, as construction on Commonwealth Avenue began, Whitney ordered that all trees presently standing be preserved when feasible and relocated to planting areas; three-thousand elm and maple trees were to be planted along the street. Whitney’s vision was for Commonwealth Avenue to be cut in two by an electric trolley, instead of horsecars or cable cars. Electric train cars were responsible for far less pollution, unlike horses whose dung had piled up on city streets and caused disease outbreaks. This problem inspired Whitney to build an electric railway. After visiting Richmond, Virginia and witnessing the innovative new electric system in the city built by engineer Frank Sprague, Whitney awarded Sprague’s company the contract to build an electric rail line from Braintree St. in Allston to Park Square in the Back Bay. By January 1, 1889, the electric trolleys were open for public transportation, and the Central Power Station, in the present-day SoWa district, opened in 1891 to power the entire West End Railway operation. Whitney remained president of the West End Street Railway Company until 1893. However, Boston soon faced a new issue. As streetcars became faster and more reliable, demand increased, and soon there were so many of the electric cars on the city’s streets that it was often faster to walk then ride, especially around high-traffic areas like the Common. Soon this pressure, along with Sprague’s introduction of the electric-powered traction motor, led Whitney and others to push for the construction of North America’s first subway route in 1897. Unlike previous projects in Europe, Boston’s subway was built using an innovative series of ditches that allowed traffic to pass overhead almost uninterrupted. This new approach to urban tunnel-building has been the standard ever since. The Beacon Street electric cars, operated by Whitney, were routed into the first subway facilities on September 1, 1897, packed to bursting with thrill-seeking passengers who acted more like they were on a rollercoaster than a public transit system.

Whitney would continue speculating and investing in natural gas, coal, and steel, including projects in Nova Scotia. But the amount of debt and loss he took on in the process meant that he did not die a millionaire. When Whitney died of pneumonia in Brookline on January 25, 1923, the New York Times found that the estate of the “supposed multi-millionaire” was only worth $1,221. Despite his challenges, Whitney had fundamentally changed the face of the City of Boston, redefining the way we interact with the city, and the routes we travel beneath it, to the current day.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Source: Familypedia; Dictionary of Canadian Biography; Don MacGillivray, “Henry Melville Whitney Comes To Cape Breton: The Saga of a Gilded Age Entrepreneur” (1979), Brookline Historical Society, Brighton-Allston Historical Society, Boston Globe, Stephen Puleo, “A City so Grand: The Rise of an American Metropolis: Boston 1850-1900” (2010), Images sourced from Allen County Library and historyofmassachusetts.org.