Jolly Jane Toppan: The MGH Nurse Turned Mass Murderer

A medical serial killer in the late 19th and early 20th century, Jane Toppan (1857-1938) admitted to the murders of 31 people and was possibly responsible for many more deaths. Toppan, a child of Irish immigrants and a trained nurse, was a press sensation in her day with her trial followed closely by newspapers such as the Boston Globe. “Jolly” Jane Toppan was finally caught after the relatives of some of her victims brought the case to light.

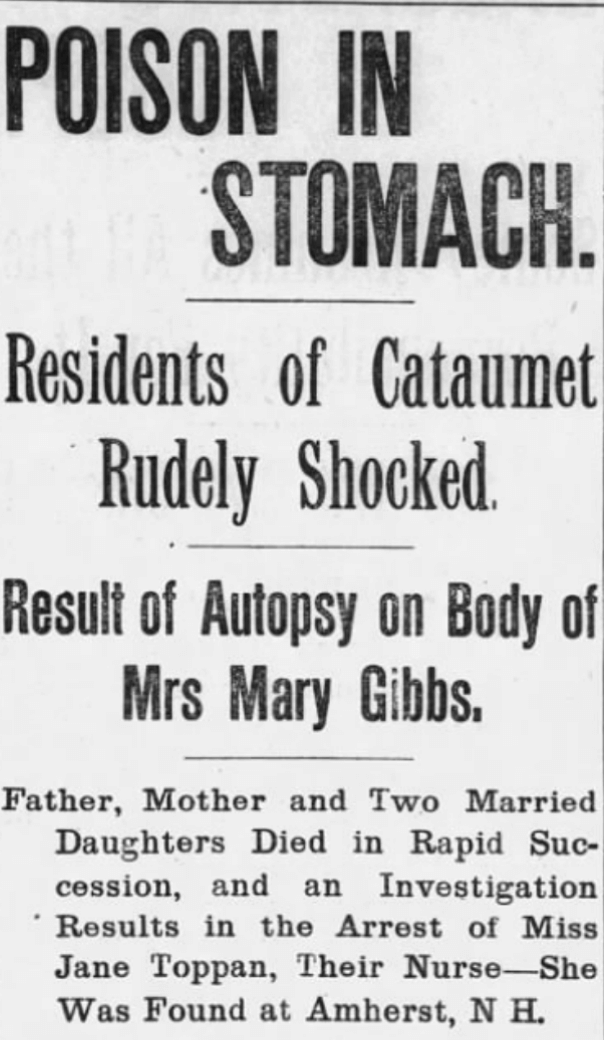

On August 31, 1901, the Boston Globe reported the tragic deaths of the Davis family of Lowell, Massachusetts who had been staying at their summer home in Cataumet, a village just north of Falmouth on Cape Cod. The ordeal began on July 3, 1901, when Mrs. Alden P. Davis seemingly died from complications of diabetes while visiting Cambridge, MA. Next, her daughter, Mrs. Genevieve D. Gordon of Chicago, who had traveled home for the funeral of her mother, fell ill and passed away on July 21st in Cataumet, reportedly from heart failure. She was followed by her father, Alden P. Davis, who died of apoplexy (stroke) on August 4. The last member of the Davis family, Mary Gibbs, another married daughter, succumbed to exhaustion after a short illness on August 13, 1901, while her husband was off at sea.

The sudden loss of an entire family naturally raised questions among locals, especially Captain Paul Gibbs, Mary’s father-in-law, who asked for an investigation into the deaths. Officials exhumed the bodies of Mary and Genevieve and performed autopsies on them in a barn near the cemetery. Specimens were brought to Harvard University by Professor Edward S. Wood, an instructor at the Harvard Medical School, for analysis. He found traces of poison in their systems. Though it was too late for the Davis family, state police detectives had already been investigating the family’s longtime family nurse, Jane Toppan, for a string of mysterious deaths of those under her care. Authorities arrested Jane Toppen on October 29, 1901 in Amherst, NH for the murder of Mary Gibbs.

Jane Toppen, was born Honora Kelly of Irish immigrants in 1857 in the North End of Boston. By the age of four, her mother had died of typhus, and her father, who suffered from mental illness and alcoholism, left Honora and her sister in the care of the Boston Female Asylum in the South End of Boston. The Toppan family of Lowell accepted Honora into their home as an indentured servant. Though the young girl had a home, attended school, and became close with the Toppans’ daughter Elizabeth, she was never adopted into the family. It was reported that Mrs.Toppan held anti-Irish sentiment, and influenced Honora to suppress her heritage. Honora eventually changed her name to Jane Toppan and claimed to others that she was Italian. It is unknown what contributed to Jane’s propensity for lying and mischief-making from a young age, but this behavior continued into adulthood. She remained in the household until the age of 28, after the deaths of Mr. and Mrs. Toppan, and then moved to the Boston area to study nursing.

Jane excelled at her nursing studies at Cambridge Hospital and then at Mass. General Hospital. During this period, she began to exhibit peculiarities in her personality, and started obsessing over and “experimenting” with her patients. Doctors held Jane’s skills in high regard but criticized her on multiple occasions for improperly adjusting the medication of certain patients. Some colleagues appreciated her outgoing, “jolly” side (thus her nickname Jolly Jane), while others felt uneasy about her natural ability to lie and spread gossip. Before Jane’s graduation, Mass. General dismissed her without a diploma in 1890 for leaving her ward shift without permission, despite passing all her exams. Though never officially registered, she went into private nursing in Cambridge and Lowell, building a reputation as one of the city’s best nurses. Jane became head nurse at Cambridge Hospital for a short time, after her predecessor and friend suddenly died, but the hospital fired her not long after for mistreatment of staff members.

For six months after her arrest, Jane was held in the Barnstable County Jail while awaiting trial. Despite suffering from occasional bouts of anxiety and depression, people marveled at Jolly Jane’s overall good cheer. Meanwhile, investigators uncovered more details of the Davis family case and Jane’s involvement. After considering several theories, medical researchers eventually settled on a combination of morphine and atropine as the poison used to murder the family. State police learnt that Jane had owed the Davises about $500 in back rent, giving her a financial motive, and a guest who was in the house at the time of Mary Gibbs’s death overheard Jane trying to get Mary to dismiss her debt to the family. Police found a chemist in Falmouth who swore he sold morphine to Jane before the deaths. Jane’s two attempts at suicide that summer after the Davis deaths raised more questions. Moreover, a growing trail of suspicious deaths from Jane’s past began to surface.

By March of 1902, Jane displayed enough unusual behavior to warrant a psychological examination. After several visits to confirm their findings, the interviewing doctors declared Jane insane on April 5, 1902. Doctors pointed to an “absence of moral responsibility”, “lack of memory” and “tendency towards untruthfulness.” Both the defense and prosecution agreed that she would end up being declared not guilty by reason of insanity. In June, Jane confessed to killing not only the Davis family by poisoning, but also to a total of 31 murders, committing her first at Mass. General Hospital. The victims included Elizabeth Toppan Bingham, the girl she was raised with; the head nurse at Cambridge Hospital whose job she took; and other complete families. Originally, Jane said her motive was a form of sexual release she experienced while being close to the dying, but later experts believed the reason was more likely the thrill of fooling doctors. When asked about suffering from any remorse, Jane answered, “I have thought it all over, and I cannot detect the slightest bit of sorrow over what I have done.” As she sat in the courtroom waiting for the jury to confirm her sentence, Jane “chatted, laughed and was exceedingly jolly.” She left the building smiling.

After leaving the Barnstaple Courthouse in the summer of 1904, Jane Toppan spent the next 34 years in the State Lunatic Hospital at Taunton, until her death on August 18, 1938. Officially she was diagnosed with ‘‘moral insanity,” but in today’s terms she would be classified as a psychopath. At the time she was pronounced the most prolific mass murderer of her time, and a regular source of study by medical and criminal experts. Admitting her decreasing memory, she later claimed her death toll could have reached 100, but she forgot many details. Though comfortable at first at the asylum, Jane later claimed abuse by the staff and suspected, ironically, that there was a plot to poison her. In 1904 she refused food and went from 160 to 80 pounds. In the end, she recovered and passed her time with little to no mention in the press, other than as a comparison to other serial murderers who came after her.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Folsom, C. Follen. (1909). Studies of criminal responsibility and limited responsibility, privately printed; Records of the Boston Female Asylum; The Boston Globe; The Boston Medical and Surgical Journal July-December 1904: Vol 151. Massachusetts Medical Society, 1904. BY HENRY R. STEDMAN, M.D., BROOKLINE, MASS.; National Endowment for the Humanities. “Western Kansas World. [Volume] (WaKeeney, Kan.) 1885-Current, August 02, 1902, Image 8,” August 2, 1902.; Paul S. Russell, MD Museum of Medical History and Innovation, Archives and Special Collections; Wicked Yankee