Marilyn Hurvitz’s Vegetable Garden

Marilyn Hurvitz, an eleven-year-old girl of Polish descent in the West End, took pride in growing a vegetable garden that was ordinarily inaccessible in tenement life.

In 1935, the Boston City Planning Board (the authority of which was transferred to the BRA in 1960) released a survey of the West End’s 5,989 ‘occupied dwellings’ comprising 20,493 residents. The report’s data was a typical review, among other findings, of how many renters lived in the neighborhood (over 90 percent of residents), how many structures were ‘unfit for habitation’ (26 percent at the time), and the median rent ($25 a month). Only four buildings in the West End had garages, which fit eight cars in total, though West End residents owned 318 cars. But only one data point from the Planning Board captured the headlines: just one resident of the West End had a vegetable garden. This was unusual for city dwellers who rarely had yards where they could grow vegetables. During World War Two, the Massachusetts Horticultural Society persuaded the City of Boston to turn back alleys, vacant lots, and sections of the city’s parks into “victory gardens” where residents grew their own food in response to the rationing of scarce goods. In 1947, a young West End girl, not yet born when the 1935 report was published, would be recognized for growing her own vegetable garden.

Marilyn Hurvitz, an 11-year-old living with her Polish family on 63 Allen St., went to the Charles River Embankment to grow her own vegetable garden. Her story was covered by Elizabeth Watts in the “Almost 21” column of the Boston Globe, where many key details were provided. The seeds she used were provided by the Junior League of Boston, a women’s organization founded in 1906 to promote volunteering for the benefit of local communities. Although the Hurvitz family lived in a tenement, that could not stop Marilyn from gardening. She told the Globe, “I would have no chance there [in an apartment] to do anything about a garden. Now three times a week I go and cultivate and weed and work in my garden. I think it’s wonderful.” Hurvitz, while growing lettuce, tomatoes, beans, radishes, and carrots, was also writing and illustrating poems for Massachusetts General Hospital’s “In Bed” Club Magazine, for children bedridden with rheumatic fever among other illnesses.

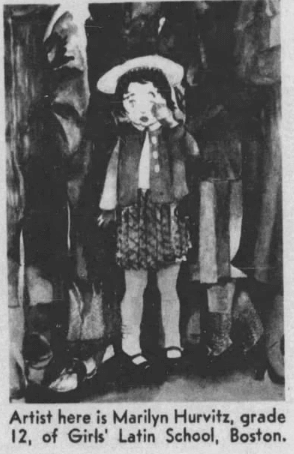

Marilyn herself had a seven-month hospital stay, and took on this hobby because she recognized how difficult the hospital visit was to endure. She said, “I know what it meant to me when I was in bed to have books and things just for me, so I like especially to do this.” Hurvitz attended Girls’ Latin School (renamed Boston Latin Academy when boys were admitted in 1972) and aspired to enroll at the Massachusetts School of Art.

That dream was realized: by 1956, Hurvitz was a junior at the Massachusetts School of Art and took classes at Boston Music School. That year, her parents announced in the Globe that Marilyn was engaged to Robert Gidez, from Brookline, who was then a senior at Bates College. She remained married to Robert until his death in 1985, and worked as a portrait artist and teacher. Marilyn passed away in 2015.

History is traditionally recorded as the legacy of towering people with grand stories. But the history of the West End comes alive not just in major events and figures, but also in the vegetable gardens and smaller aspirations of the neighborhood’s children.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Boston Globe (Elizabeth Watts, “West End Girl Tends Garden on Embankment,” July 15, 1947; “Photo Standalone 29 — No Title,” April 29, 1956, C71); Massachusetts Horticultural; geni.com; Washington Post