Prescott Townsend

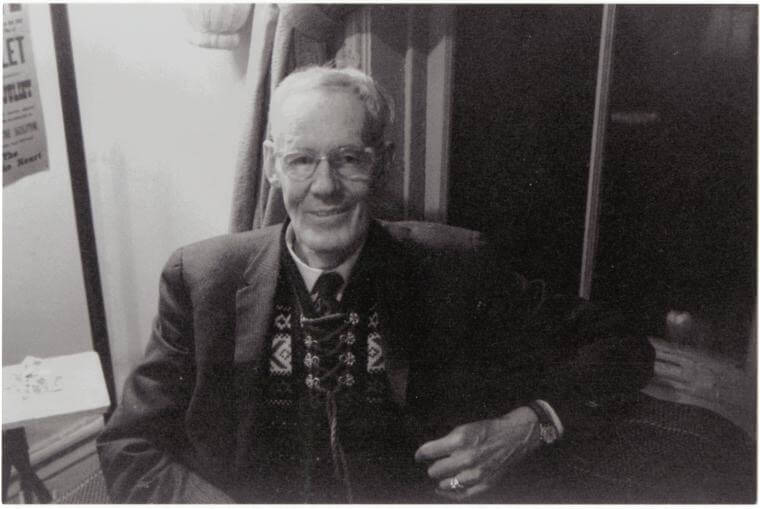

Prescott Townsend (1894-1973) was a gay activist who lived on the North Slope of Beacon Hill from the early 1920s until his death in 1973. He was outspoken and proud of his identity, from boasting about his pilgrim ancestors to organizing early LGBTQ+-oriented groups in Boston.

Prescott Townsend was born on June 24, 1894, into a Boston Brahmin family with ancestry traceable back through the American Revolution to the Mayflower. He was the fourth of five children and was raised in Back Bay and sent to prep schools typical of his class. When he was nineteen years old, in around 1913, he came out as gay to his family, who he described as generally accepting; however, they also warned him to be careful, mainly out of fear that it would reflect poorly on the family name. He enrolled at Harvard College in 1914. Though his tenure there was technically cut short by the United States’ involvement in World War I and his enlistment in the Navy Reserves in 1917, he was awarded a degree as a man in service in 1918. After being discharged in 1919, he attended Harvard Law School for one year before spending 1920 in Paris, where he was immersed in the culture of the Lost Generation. He was determined to bring the bohemian lifestyle back to Boston.

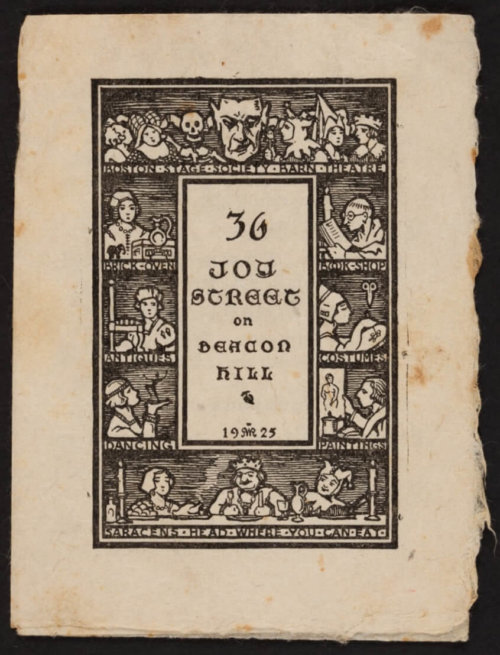

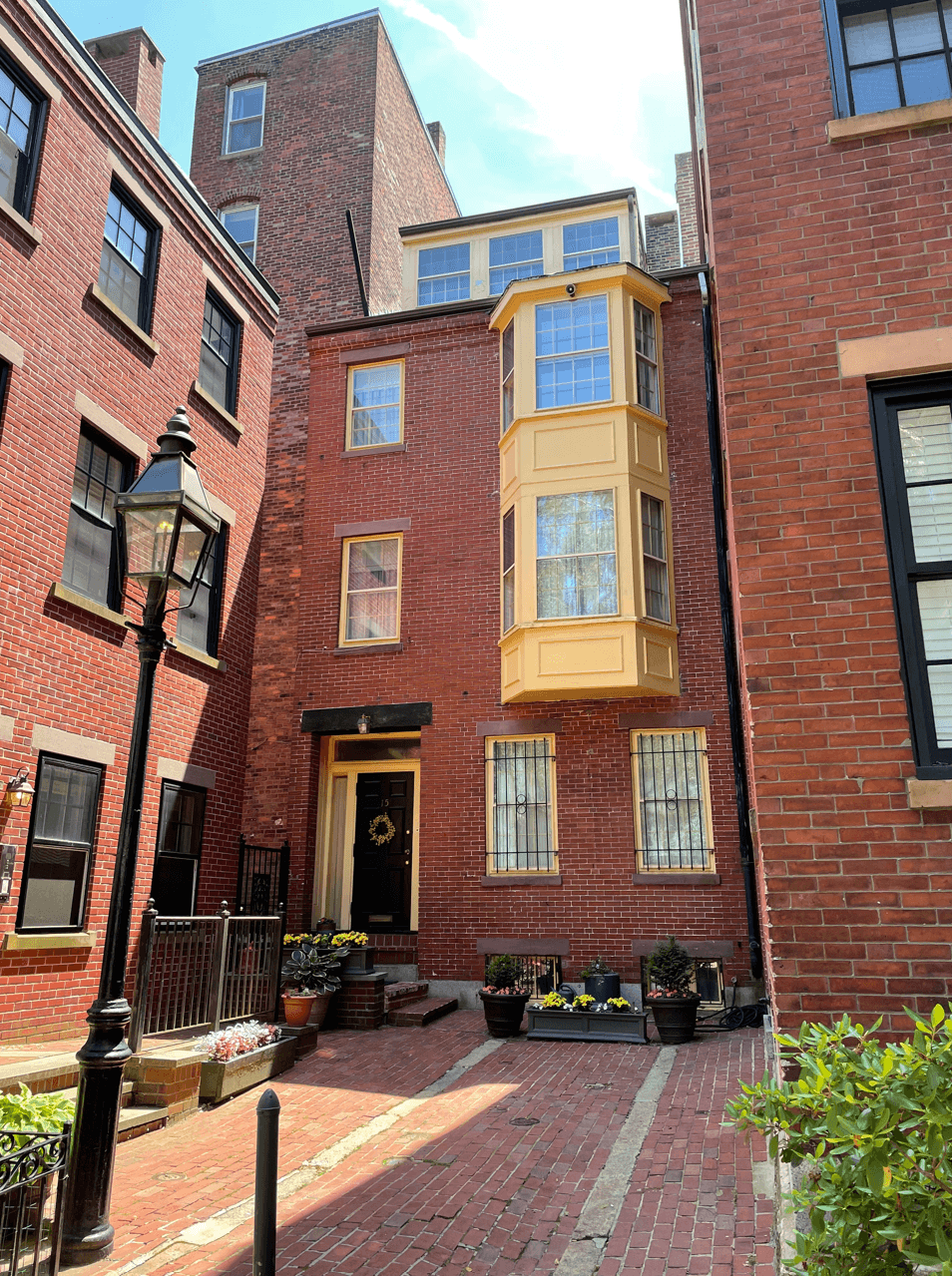

Upon returning to the United States, Townsend purchased multiple properties on the North Slope of Beacon Hill in the historic West End, which he rented out as apartments, shops, and artists’ studios. In 1926, he agreed to rent the Barn at 36 Joy Street to the Boston Stage Society, which he also funded. This venture joined the Brick Oven Tea Room speakeasy (opened in 1923) on the same lot, as well as a number of other small businesses selling everything from chicken & waffle dinners to books to dance lessons to “unusual photography.” This era was the epitome of bohemian life in Boston, full of outlandish characters and dastardly deeds, though it is difficult to nail down what is fact and what is fiction. Sadly due to the Crash of 1929, Townsend had to sell all of his buildings on the Hill except for 75 Phillips Street and 15 Lindall Place, which connected through the basement.

In 1993, Alfred “Ellie” Cutler mentioned Prescott Townsend in a memory letter to the West Ender newsletter. Cutler lived on Grove Street and then on Phillips Street between 1935 and 1951. He recalled that Townsend ran a business on Phillips Street called the Jolly Roger, and that no one seemed to know what was sold there. He also said that Townsend “had a 1927 Chrysler convertible that he once loaned to Leo Slabine (Slaby) and myself and one other feller. We drove the car to the Burroughs Newsboys camp which at that time was in East Jaffrey, New Hampshire and remained overnight.” Ralph Saya wrote a letter to the West Ender in response to Alfred Cutler with a story about the Jolly Roger:

At 73 Phillips Street, I was next door to the “Jolly Roger” and like Mr. Cutler, didn’t know or care what they sold there until one day while playing with a ball on my roof, the ball bounced down onto the roof next door. Not wanting to lose the ball, I decided to go down and ask the owners of the building next door, (the Jolly Roger) if I could go onto their roof to retrieve my ball. I rang the bell several times and getting no answer, tried the door. Amazingly, the door opened and I entered what appeared to be a single-family house. As I stood inside the door, wondering what to do next, a woman came out of one of the rooms naked as a jay bird. Seeing me, she scampered into the next room. I was frozen to the spot. At this point, an elderly woman came from the same room and in a booming voice asked me what I was doing there. Frightened, I replied meekly that I wanted to retrieve my ball from the roof. She replied by asking, “did you see anything?” After assuring her that I had seen nothing, she pushed me out the door, with the assurance that she would get my ball and have it [delivered] to me, “-but don’t come into this house again!” I was much older before I realized what was being sold there. If Mr. Cutler is at all curious, this story should fill the void.

These stories illustrate how Townsend’s sexuality was perhaps not at the forefront of his neighbors’ minds, especially when there were other lascivious things going on behind closed doors (or when there was the benefit of a car to lend).

Townsend’s life was interrupted in 1943 when he was arrested and charged with performing a “crime against nature” with a young man in a doorway on Mt. Vernon Street. He refused to pay the fine (or perhaps it was a bribe?) of $15.00 and was sentenced to 18 months at Deer Island House of Corrections. He was released on V-E Day, but he became ostracized from Brahmin society and was quietly removed from the Social Register around this time. Secondary sources vary and primary documentation is difficult to find, but around this time—some sources say he started in the 1930s, others that he didn’t begin in earnest until after his release from jail—Townsend regularly went to the Massachusetts State House to speak about repealing the anti-sodomy laws and to petition for the enactment of legislation protecting homosexual people. There is speculation that he was at first only allowed to speak because of his societal status, but there is also reason to believe that his fiery, outspoken personality enabled him to continue the work even after his jail sentence.

In the mid-1950s, Townsend began organizing the “first social discussion of homosexuality in Boston,” meeting in the basement of his home at 75 Phillips Street. Eventually, these meetings were associated with the Mattachine Society, an underground gay men’s group founded in Los Angeles by Communist organizer Harry Hay. The Mattachine of Boston continued meeting mainly at Townsend’s residences on the Hill through February 1959 — by that time, there were 97 people on their newsletter mailing list. After this period, the meetings were moved to the Parker House Hotel and other venues, and the group eventually had a falling out with Townsend due to disagreement on the purpose of the society. Overall, the meetings held an overtly positive tone and emphasized both the validity of the gay identity and the importance of finding community with other like individuals, a value that was common in the West End at the time. The society also encouraged members to think about their national positionality and remember that there were other branches of the Mattachine Society in cities all over the United States facing the same struggles. Townsend went on to found the Demophil[e] Society, another short-lived LGBTQ+-oriented group. Around this time, which would have been the early 1960s, Townsend developed his “Snowflake Theory” of sexuality: that no two people have the same sexual preferences, and that people can be described as a snowflake with six points of varying degrees, “I/You,” “He/She,” “Hit/Submit.”

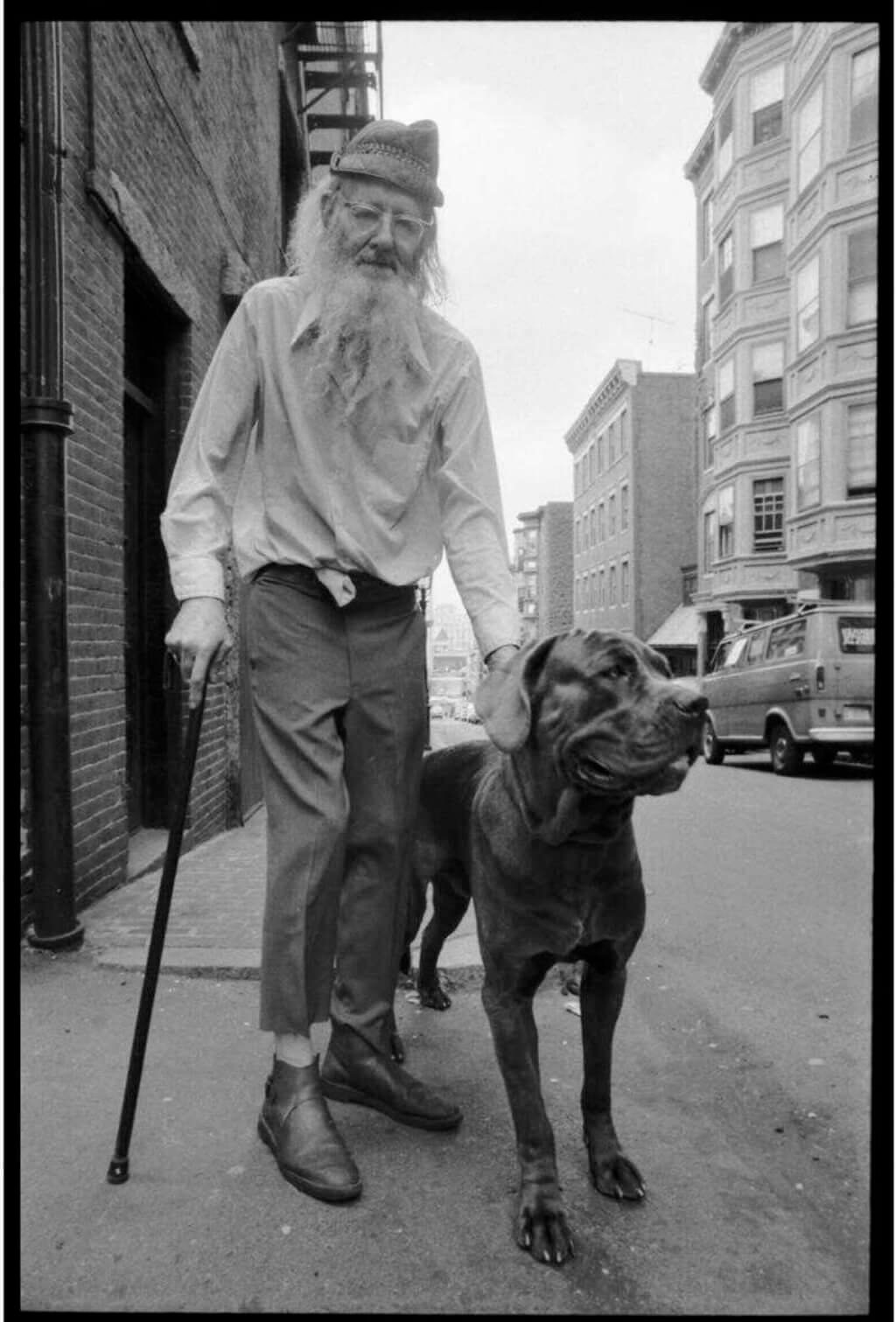

At this point, his connecting homes on the North Slope were cluttered with belongings, but allegedly, these did not include a refrigerator, television, telephone, or radio. Throughout the 1950s and 60s, he rented rooms in both Provincetown and Boston to runaways, hippies, and artists for cheap. His tenants included John Waters, Stephen Jonas, and Rene Ricard, among others. In the late 1960s, he fully embraced hippie culture in his own aesthetic, growing his hair and beard long — a marked contrast from his clean-cut youth, though he was consistently known for wearing a long raccoon-skin coat. P.T. (as he was known to his friends) even traveled to New York City in 1970 for the first Pride Festival on the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. Sadly, his homes in Provincetown and Boston were damaged or destroyed by fires between 1968 and 1971, leaving far less material on the early 20th-century LGBTQ+ community in Boston for the historical record than he had collected in his lifetime. He died in the house of a friend on Garden Street on May 18, 1973. Though his legacy is not without controversy, Prescott Townsend was a significant figure in early Boston LGBTQ+ activism, who made his home for many years in the West End. Randy Wicker, a friend from near the end of Townsend’s life, wrote in a Christmas newsletter in 1994: “[Prescott’s] was a happy full life filled with friends of all ages, sexes and orientations. Through him, I came to understand that a gay person could live a vibrant & exciting life into old age, thereby greatly reducing my own personal terror of growing old.”

Article by Emma Beckman, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Lucius Beebe, Boston and the Boston Legend (New York: D. Appleton-Century, 1935); Alfred H. Cutler, “Down Memory Lane,” The West Ender, March 1993, Vol. 9, no. 1 (West End Museum Digital Archive); Mark Herz, “In a Neighborhood That Once Shunned Him, a Boston Gay Rights Pioneer Finally Gets His Moment,” GBH, June 19, 2023; Theo Linger, “Prescott Townsend (U.S. National Park Service),” National Parks Service; Meg Metcalf, “Research Guides: LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resource Guide: The Mattachine Society,” Library of Congress; Prescott Townsend Papers and Photographs, Special Collections, Boston Athenaeum Library; Ralph Saya, “The Jolly Roger,” The West Ender, September 1993, Vol. 9, no. 3 (West End Museum Digital Archive); Charles Shively, “Prescott Townsend (1894-1973): Bohemian Blueblood – A Different Kind of Pioneer,” in Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context, edited by Vern L. Bullough (Oxford, UK: Taylor & Francis Group, 2002); Randy Wicker, “Xmas Letter 1994,” Digital Transgender Archive, 1994.