The Haymarket Relief Station

In the later half of the 19th century, Boston’s downtown residents required more immediate access to acute medical care as industrialization brought with it additional hazards to safety and health. For over thirty years the Haymarket Relief Station, which sat at the eastern gateway of the West End, filled that gap by providing much needed treatment for acute illnesses and injuries for urban residents.

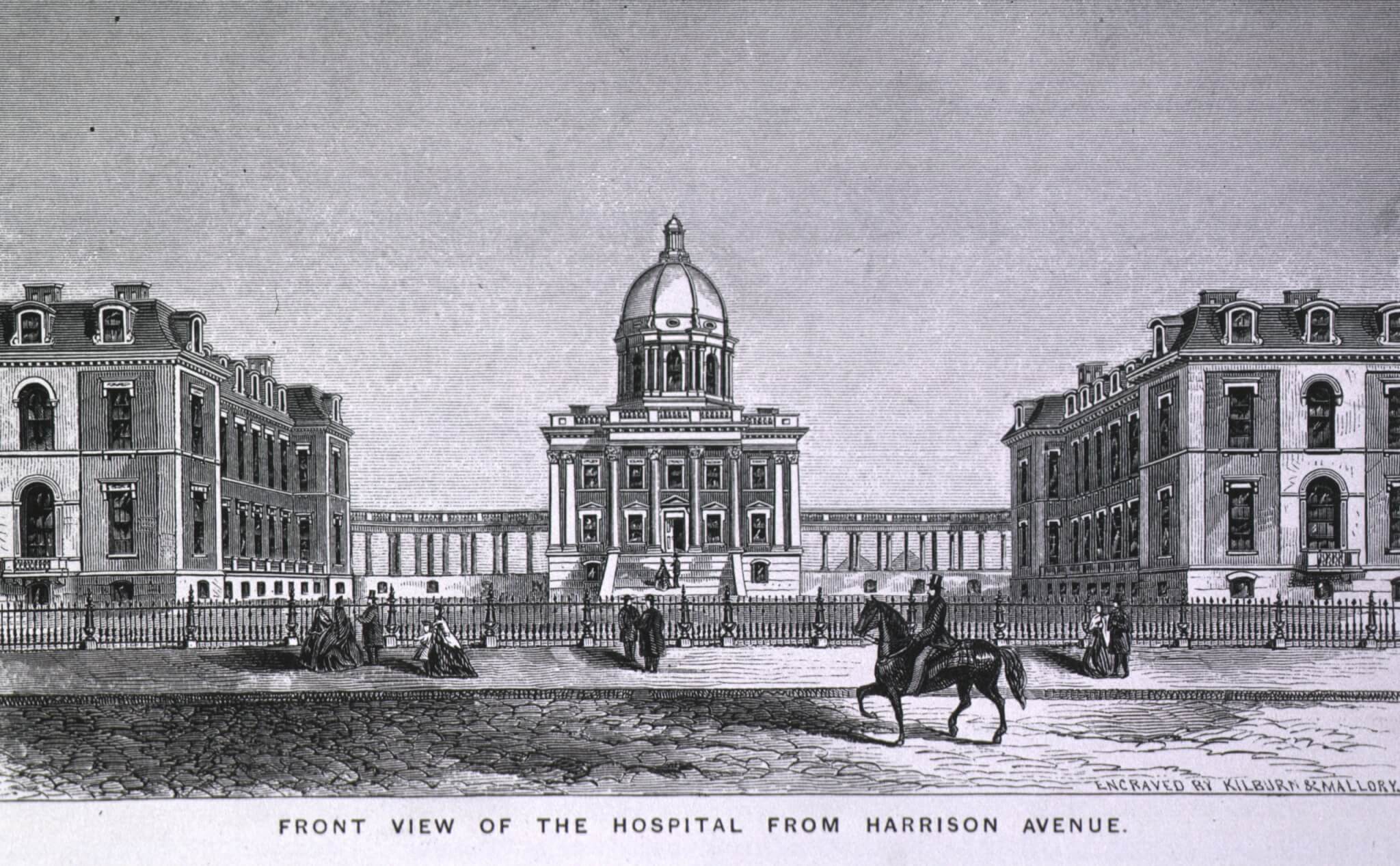

In 1858, on the cusp of Boston’s industrial and greatest immigration period, the City of Boston authorized the creation of a new hospital whose purpose was the “reception of those sick and injured: citizens of Boston who, from any cause, were unable to otherwise obtain care and treatment,” especially in cases of “acute illness and for the victims of accident or injury.” This new hospital would become the Boston City Hospital, made possible through the donation of $26,000 from Elisha Goodnow of South Boston, who stipulated that the hospital had to be “situated in Ward 11 or 12”, which at that time included South Boston and the South End. Officials ultimately chose the South End as the site for the new hospital because South Boston was considered too distant for downtown patients.

At the turn of the century, however, downtown residents complained that the City Hospital was still too far away for victims of accident or sudden illness to reach in a timely way. Bending to public pressure, the trustees of Boston City Hospital, having just received a generous donation of both cash and a lot of city land on Haymarket Square” freed up from construction of Boston’s new subway, authorized the construction of a new relief station. Dubbed the Haymarket Relief Station, the new facility would be a “first-class hospital” in every way, but its primary purpose would be to “afford better facilities for the immediate treatment of accident cases”. The new hospital was housed in a brand new three story structure on the site of the former Boston and Maine Railroad Depot, built of brick, with a granite foundation and trimmings. An additional half-story in the rear was used by the station’s horse-drawn ambulances. The station had a frontage of 71 feet along Haymarket square and extended 130 feet back along Canal Street. Its vicinity to the wharves, railroads, and manufacturing center of the city was the perfect location to treat downtown patients, and even those in East Boston and Charlestown more quickly without circumventing traffic to the parent hospital.

After construction delays caused by the unexpected discovery of the bed of the former Middlesex Canal during excavation, the station cleared its formal inspection and was dedicated at a reception attended by Mayor Patrick Collins, members of the city council, and other dignitaries. The Haymarket Relief Station opened on February 20, 1902, and on its first day of operation, doctors and staff saved the life of a man who had attempted suicide by ingesting carbolic acid. A Boston Globe reporter speculated that had the patient been transported to the more distant Massachusetts General or City Hospitals, he would have surely died.

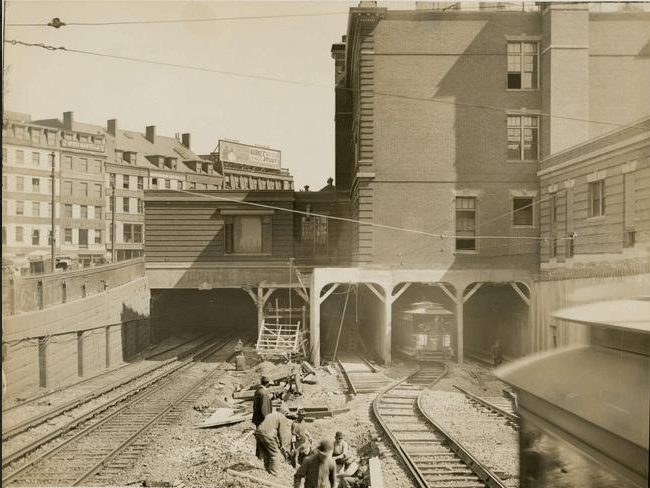

A study of the treatments conducted at the Haymarket Relief Station during its history provides interesting insight into common health issues at the time. Industrial and transportation accidents were common in the day, such as the accident occurring in August of 1906 almost directly under the station itself. When the motor of a Boston Elevated Railway car failed on an incline, it rolled backwards into the subway tunnel it had just exited, striking another car behind it. The result was an explosion of splintered wood and broken glass that injured multiple passengers. Fortunately, rescuers were able to walk most of the injured to the Relief Station only a short distance away. Injuries from fireworks were very common before organized, city-controlled fireworks celebrations. Each year, the Relief Station and other hospitals had to prepare for Fourth of July injuries and even fatalities. On June 19, 1909, the aftermath of the annual Bunker Hill Day celebration filled the wards of the Relief Station and other Boston Hospitals with over fifty cases of gunpowder burns, most to the hands and face, and one man suffered a bullet wound to the hand. Though this many injuries from one celebration may seem unusual today, the Globe reported that in 1909 “as compared with a few years ago before the police department insisted upon a sane celebration of the holiday, the number of accident cases Is light.”

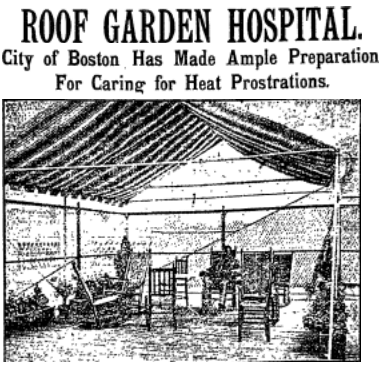

Before widespread access to central heating and air conditioning, climate extremes (i.e. heat and cold waves) could be harmful or fatal to many urban residents. Those suffering from heatstroke or frostbite in the first half of the 20th century could go to the Haymarket Relief Station for assistance. In 1902, the Boston Globe reported on the rooftop treatment program at the Relief Station:

On the ample roof, railed in so that no delirious patient could by any possibility throw himself into the street, there are bath tubs in which patients may be immersed in ice water to reduce their temperature, there are cots and hammocks, and there is everything else that experience in medicine has taught the physicians are desirable in treating heat cases.

In 1934, the Relief Station treated over 200 cases of frostbite during one of the worst recorded Cold Waves in the country, with temperatures reaching minus 18 degrees Fahrenheit.

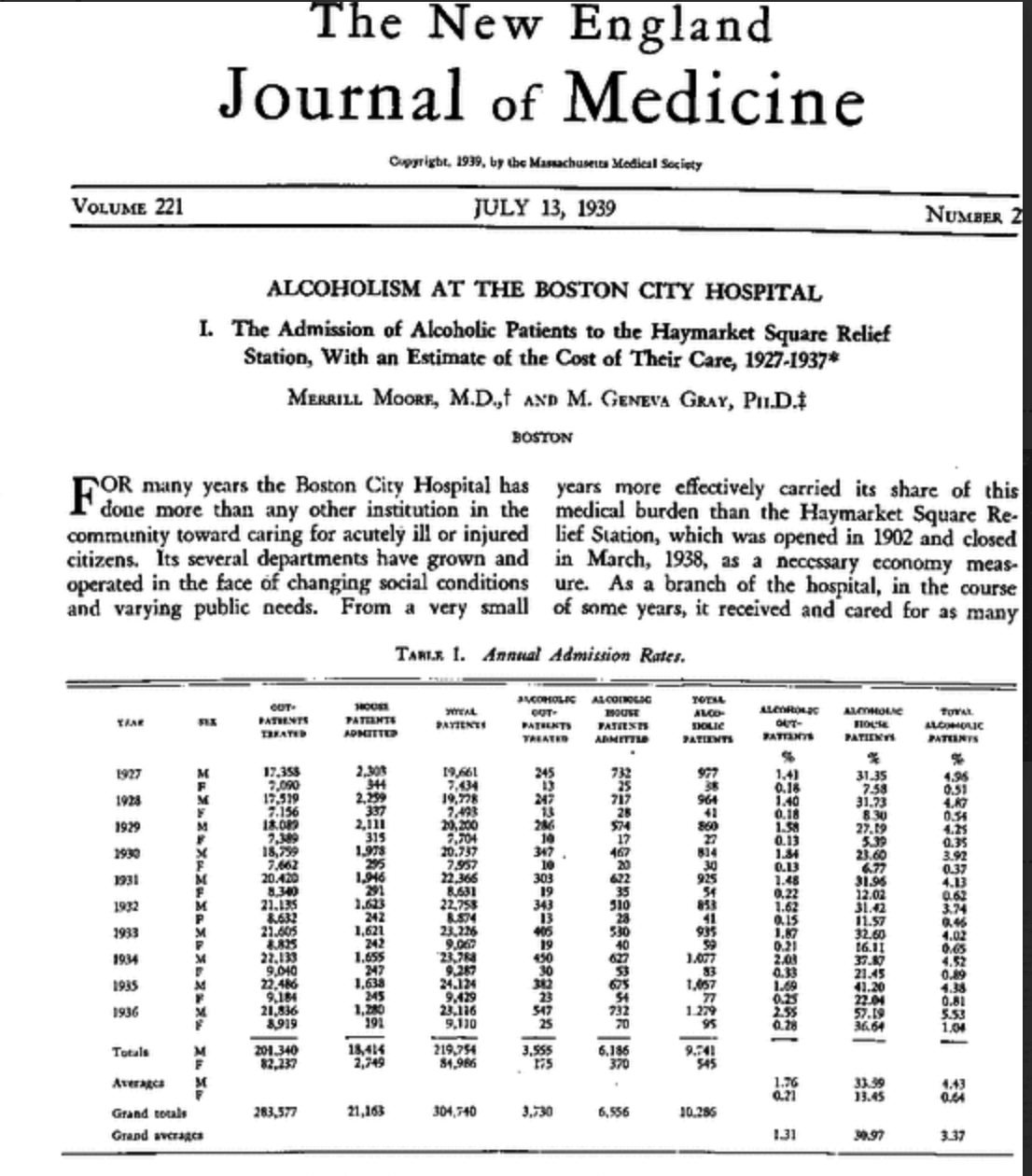

During its years of operation, the Haymarket Relief Station was recognized as the key facility for treating alcohol related illnesses in Boston; a problem that became a scourge of the city and many others when unregulated liquor production ran rampant during Prohibition. In a 1939 report on Alcoholism, the New England Journal of Medicine recognized the Haymarket Relief Station (by this time closed) for its efforts in treating 1400 patients a year “suffering from various stages of physical disability associated with the excessive use of alcohol. During the New Year’s holiday celebration of 1927, the Relief Station was one of the city’s hospitals which treated 75 patients poisoned by a “death alcohol” which had killed ten partygoers in the Boston area and fifty in New York City. During the Legion convention period in Boston in 1930, the relief station treated some of the 358 celebrants who suffered from temporary blindness, paralysis, and complete incapacitation due to over drinking. These patients were luckier than two West End partygoers, Charles and Mildred Henry of 37 Lynde Street, who lost their lives during this time from drinking tainted rum.

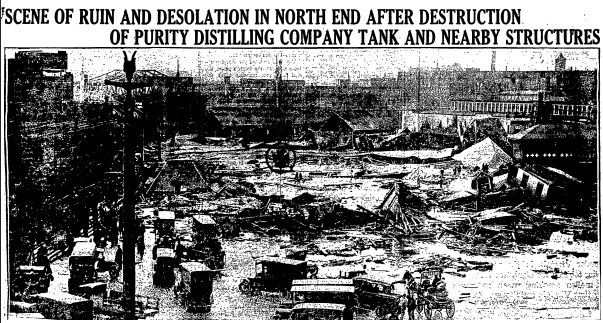

On January 15, 1919, a 50-foot-high storage tank belonging to the Purity Distilling Company, located at North End Park along Commercial Street in Boston, burst, creating shockwaves and a flood of 1,500,00 gallons of molasses. The tide of sticky molasses swamped the immediate vicinity, causing nearby buildings to collapse and covering everything in its path, including people and animals. Rescue workers from the Police, Navy, Army, hospitals and ambulance services quickly searched for survivors, 42 of whom were brought to the Haymarket Relief Station just hundreds of feet away. The scene at the Relief Station was described in the Boston Globe:

Every room on the two floors of the building was filled with the injured, and nurses and orderlies, their clothes covered with molasses streaks, hurried about, pushing equally sticky stretchers. While in the rooms they cut off the clothes which were too saturated with the heavy liquid to be removed, clinging about the bodies of the victims. The molasses itself was removed from the men’s bodies by warm water. and the men made comfortable between clean sheets.

Joining the injured and medical staff were a throng of anxious people searching for news of loved ones who lived or worked near the disaster site. Of those victims brought to the Relief Station, all but five were released after treatment; three were dead upon arrival and two patients died in hospital.

Despite the good work being done there from the start, The Haymarket Relief Station was almost closed in 1907, just five years after opening. In that year, the Transit Commission announced that it needed to add two tracks to the four subway tracks already running under the Relief Station for the development of the Washington Street Subway line. The addition of the two tracks would remove what was left of the Relief Station’s basement which housed its heating system and ambulances. Relief Station Staff strongly protested, citing the facility’s importance to the 50,000 downtown residents treated there every year. The crisis was finally averted when the city ceded an adjoining lot to the Relief Station, on which it could build a new extension to hold its heating system. There was no such luck in 1938, after Mayor Maurice J. Tobin ordered the closure of the Haymarket Relief Station as part of budget cutting measures. His reasoning was that “the Haymarket Relief was built in 1901…at a time when transportation to the hospitals were in horse-drawn vehicles. It would never “have been built in this modern age of motor transportation.” Maybe Mayor Tobin would not have been so confident in the future of motor travel if he himself had ever been stuck in rush hour traffic on the bridge bearing his name.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Sources: A HISTORY of the BOSTON CITY HOSPITAL FROM ITS FOUNDATION UNTIL 1904, AUTHORIZED BY THE TRUSTEES AND EDITED BY A Committee of the Hospital Staff: David W. Cheever, M.D. A. Lawrence Mason, M.D. George W. Gay, M.D. J. Bapst Buake, M.D., BOSTON MUNICIPAL PRINTING OFFICE, 1906; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Jan 2, 1902; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 6; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Feb 5, 1902; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 6; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Feb 6, 1902; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 4; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Feb 21, 1902; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 11; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Aug 4, 1902; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 9; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Jul 18, 1906; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 1; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Aug 8, 1906; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 4; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Aug 17, 1907; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 6; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Oct 9, 1907; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 10; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Jun 18, 1909; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 3; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Jan 16, 1919; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 1; Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Jan 18, 1919; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 1; Boston Daily Globe (1923-1927); Jan 2, 1927; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. C1; Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960); Oct 10, 1930; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 1; Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960); Feb 10, 1934; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 1; Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960); Sep 5, 1937; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. C1; Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960); Jan 30, 1938; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. B1; Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960); Mar 20, 1938; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. B17; Daily Boston Globe (1928-1960); Oct 19, 1938; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Boston Globe, pg. 8