The Powars-Kennedy Murder Case

Michael Powars carefully planned the murder of his cousin, Timothy Kennedy, but his fatal mistake was thinking that the law required an eyewitness to convict someone of a crime.

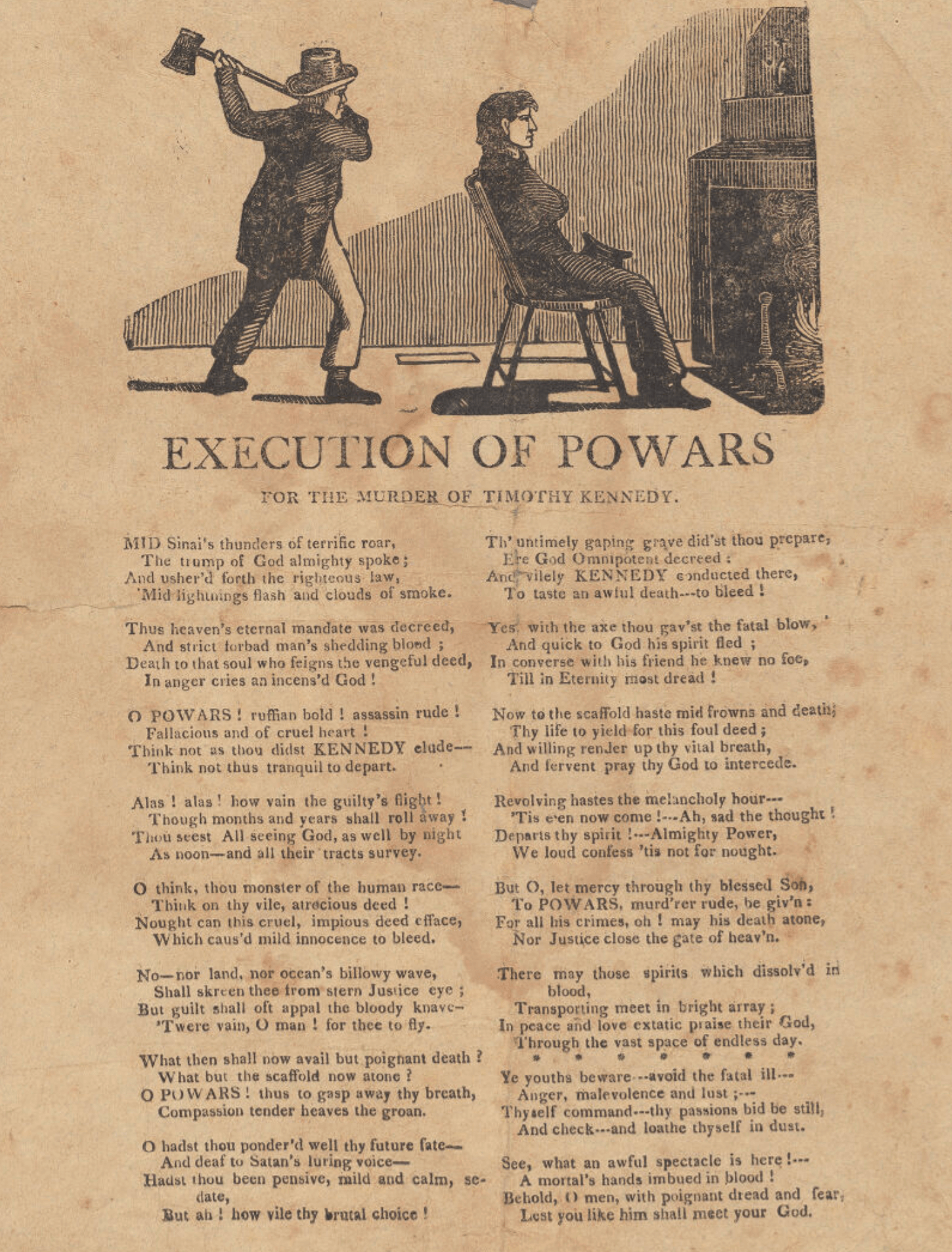

On May 26, 1820, a somber procession of horse-drawn carriages steadily approached the gallows on Boston Neck. In the lead vehicle were Michael Powars, a 51 year-old Irish immigrant, and his religious advisor, Rev. Larissey. Behind them rode various public officials, and a cart “bearing the malefactor’s coffin.” The journey had begun at 10:00 a.m. from the jail on Court Street, where Michael Powars had spent over two months for the murder of his cousin, Timothy Kennedy.

This tragic family tale began innocently enough in 1817 when Powars returned to his home in County Wexford, Ireland. He had been living in the United States since 1802, after first moving to England to escape possible arrest for his part in the failed Irish Revolution. Powars worked hard as a laborer in his new country and was able to save a decent sum of money. Soon after Powars returned home, however, he realized that there was little opportunity for him there and he planned his voyage back to Boston. Before leaving, he convinced his cousins, Michael McDonald, John McDonald, and Timothy Kennedy, to return with him, and generously loaned them the funds to pay for their voyage.

Once settled back in Boston, Powars began asking his relatives for repayment of his loan, but had little luck. For the most part, they ignored him. In 1818, after his own attempts failed, Powars filed suit against Timothy Kennedy and Michael McDonald. The court not only dismissed the cases due to a lack of evidence (Powars had not created written contracts for the loans), but also ordered Powars to pay Kennedy $5.08. They even threatened to jail him for perjury. In the end the case was dropped, but Powars became enraged and even more driven to receive satisfaction.

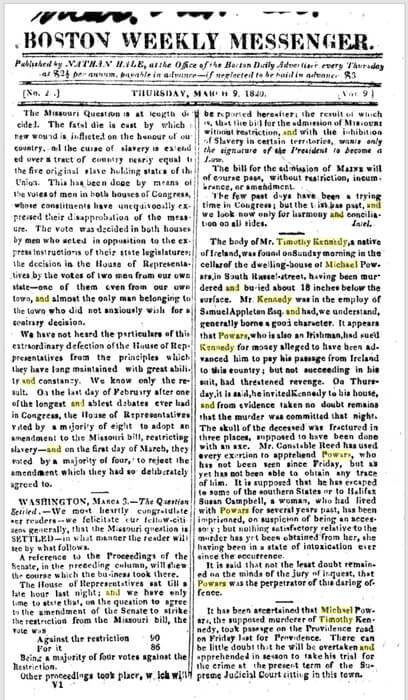

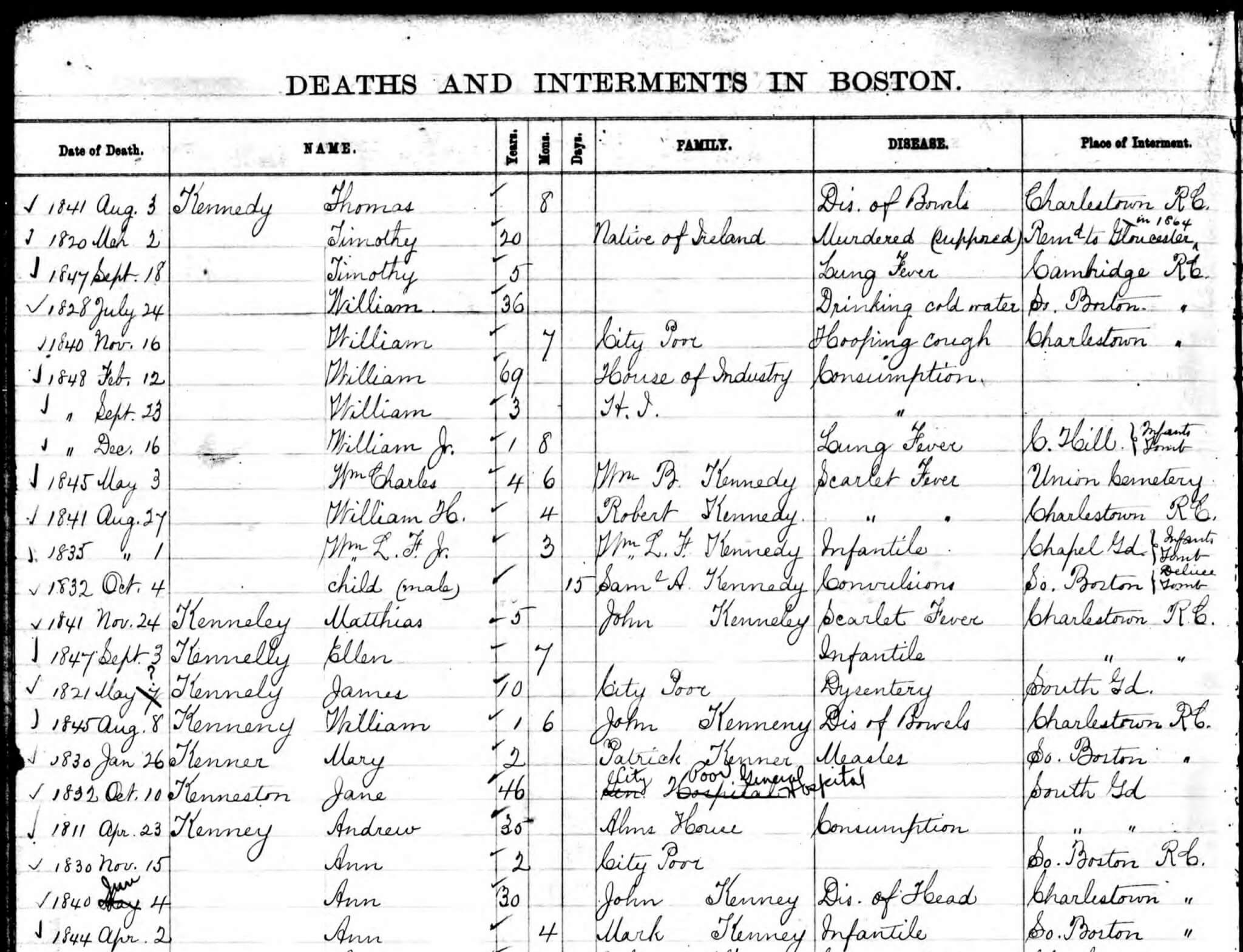

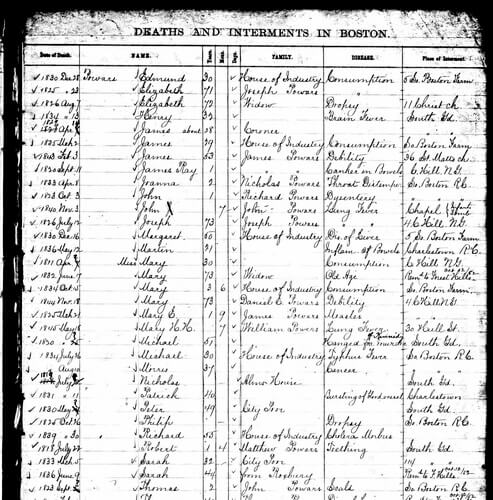

Future witnesses painted a picture of a man possessed. People reported that over the next two years Powars closely tracked Kennedy’s activities, especially his spending habits. On multiple occasions Powars openly promised to kill Kennedy over the matter of the debt. On Sunday, March 5, 1820, when Kennedy’s employer and a constable found the missing Kennedy’s body in Michael Powars’ basement at 46 South Russell Street, there was little doubt how high Powars’ obsession had climbed. Police reported that Kennedy’s head had been fractured, most likely with the head of an ax, and that his face and chest were burned. They believed Powars was guilty of the crime, but he was nowhere to be found.

During her police interview, Powars’ live-in partner, Sarah Campbell, testified that on Friday, March 3, Powars said he was leaving for Mobile, AL. In reality, Powars had fled to Providence by foot, and then sailed to Philadelphia from where he had booked a voyage back to Ireland. Unfortunately for Powars, an acquaintance from Boston was in town, recognized him, and reported this to local police. Philadelphia police arrested Powars on March 15, 1820. He had with him a trunk containing clothes and a notebook identified as belonging to Kennedy. Before transporting Powars back to Boston for trial, police informed him that he had been accused of Kennedy’s murder. At this he became annoyed and stated that he was not guilty, insisting:

“that no man living could prove it.”

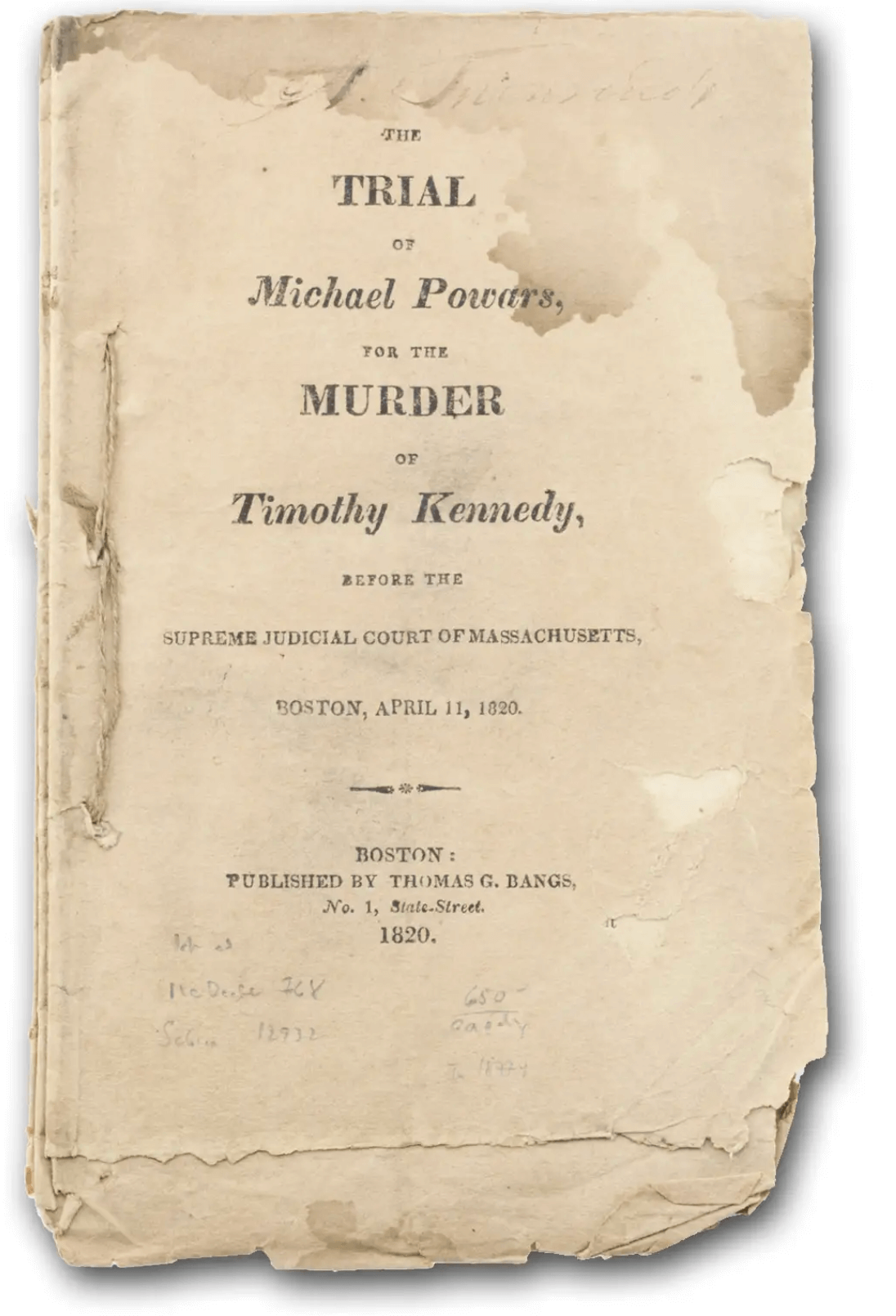

The trial of Michael Powars opened on April 11, 1820 at the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. His court-appointed legal team was led by none other than Daniel Webster, the top legal mind of the age. Leading off the prosecution’s case was coroner Thomas Badger, who described Kennedy’s head wound as likely caused by an ax head, and to “have been given with sufficient violence to knock down a bullock” (i.e. bull). Kennedy’s burns probably occurred from the victim falling into the fireplace after the fatal blow. Constable George Reed, who discovered the body buried in the accused’s basement, found an ax in Powars’ apartment, which was marked with blood and hair. Reed also saw blood stains on the floor and near the cellar entrance.

The prosecution used other witnesses to recreate Powars’ actions before and after the murder. Powars’ neighbor, Mr. Dobson, also Kennedy’s tailor, saw him and Kennedy enter Powars’ house on the afternoon of Thursday, March 2. Dobson also identified the suit found in Powars’ trunk as one he had made for the victim, as well as Kennedy’s notebook. Mrs. Dobson testified that she saw Powars leave alone a few hours afterwards with a “trunk under his arm.” Sally Hewes, the owner of Kennedy’s boarding house, reported that at 5:30 p.m. on March 2, Powars arrived at her house and oddly asked to use a room to change in, yet he only wanted to change in Kennedy’s room. He left with his trunk, and she noticed afterwards that Kennedy’s own trunk had been unlocked.

On the second day of the trial, defense witnesses described Powars as a hardworking man and incapable of committing such a violent crime. The defense team urged the jury not to be lured into a false decision based solely on circumstantial evidence. Yet, twenty minutes after being sent to deliberate Powars’ fate, the jury returned a verdict of guilty. On hearing the judgement, Powars complained:

“I think the court very dishonorable. I am not guilty. It has not been proved that I am guilty. If there was one witness that proved that I am guilty, I should be satisfied.”

Upon sentencing, Chief Justice Isaac Parker scolded Powars for having “long brooded over a supposed injury from the victim of your revenge” and that “you fancied yourself safe, because your dreadful orgies were seen by no human eye.” He then sentenced Powars to death.

While awaiting his execution, Powars recited his life story, and wrote a will, leaving money to his family in Ireland, and $50 to charity. He even left a “half eagle” ($5) to each of the three women who testified against him. Powars unsuccessfully petitioned the governor of Massachusetts for a pardon, or at least a quick execution if a pardon was not forthcoming. When he finally stood at the gallows on May 26, 1820, witnesses described Powars as calm and neatly dressed. Just before officials placed the hood over his head, he uttered his last words:

“God bless you! I forgive all!”

At 11:00, seconds after the trap door opened, Michael Powars repaid the debt that he owed his victim, and cousin, Timothy Kennedy.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Sources:The Concord Observer, June 5,1820; Boston Weekly Messenger, March 9-April 20, 1820; Powers, Michael. Life of Michael Powers: Now Under Sentence of Death for the Murder of Timothy Kennedy”. Russell & Gardner: Boston, 1820.; Spear, William S. The Trial of Michael Powars for the murder of Timothy Kennedy, Boston:Thomas G Bangs,1820.; Watchman, Christian. “Trial of Michael Powars,” The Daily Advertiser. Apr 15, 1820.