The West End House’s Debate Clubs

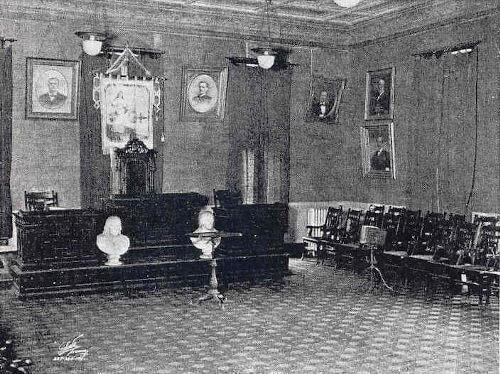

In the early twentieth century, the West End House hosted debates between high school literary societies on controversial and important issues. The debates were judged by lawyers and educators in Boston and adopted the format of competitions at the collegiate level.

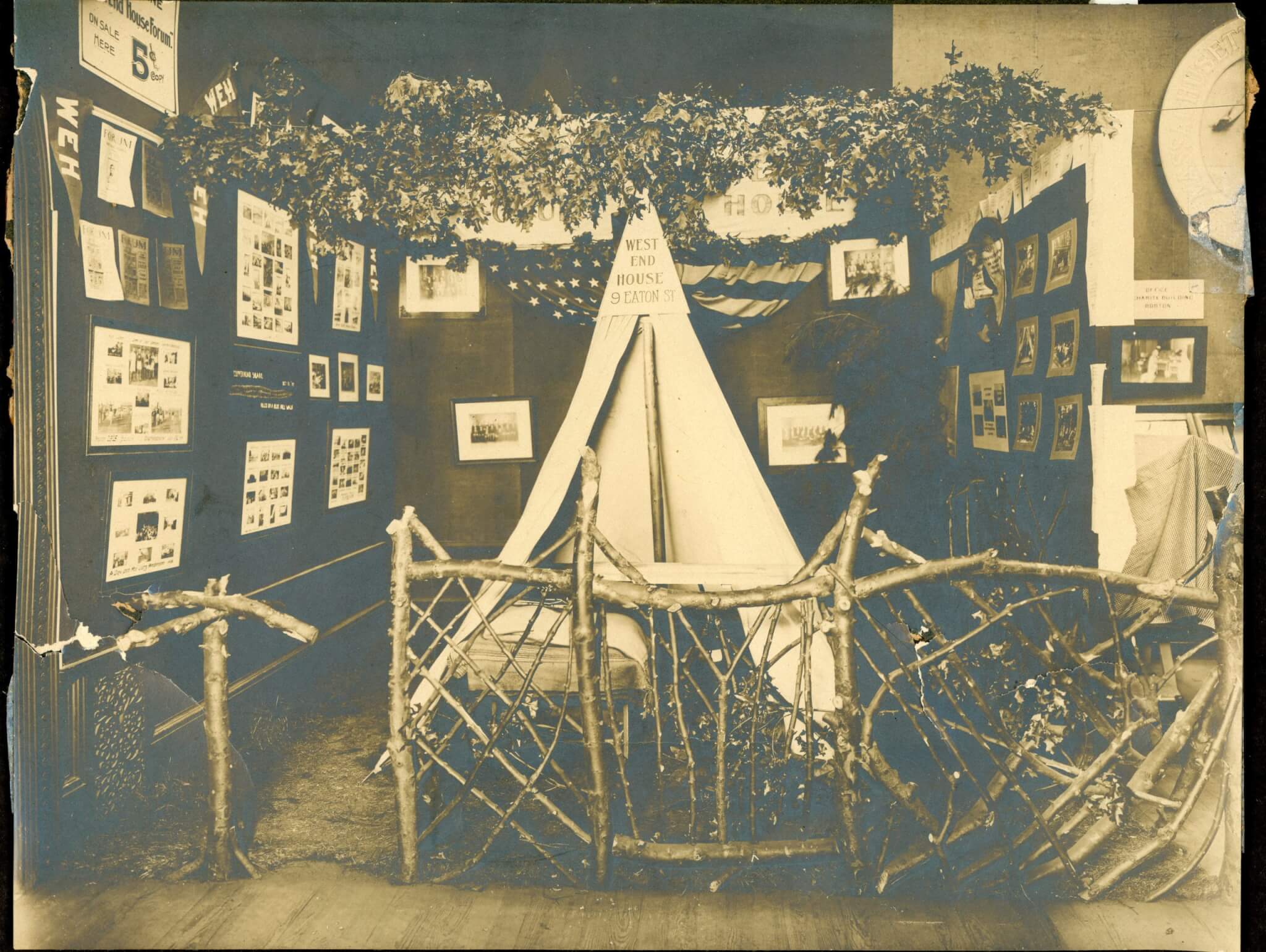

The West End House originated from the Young Men’s Excelsior Association, founded by Jewish immigrant boys in the neighborhood in 1903. When philanthropist James Storrow met the Association’s members, he put his money toward building a new facility for them in 1906. The West End House became a community center for people from the neighborhood’s many immigrant communities, and hosted activities as varied as boxing, basketball, and theater. One of those activities involved a battle of minds, through debate clubs which met at the West End House to debate a proposition that was proposed in advance.

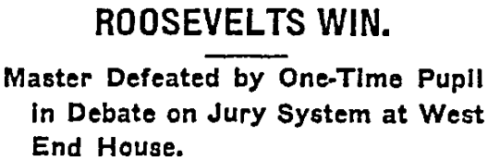

The “debating club” of the West End House first met in the evening of October 16, 1909. Under the auspices of this club, the West End House was a location for debates between teams of 14-to-17-year-old boys from local high schools. The debaters represented uniquely named literary societies, which were the precursors to modern debate teams. On February 13, 1911, the “Roosevelt Literary Club” and “Fulton Club” convened at the West End House to debate the resolution, “Resolved, that the present jury system be abolished.” The Roosevelt Club, represented by Harry Jacobs, Harry Hoffman, and Cyril Hollander, took the Affirmative side in support of abolishing the present jury system. The Roosevelts were coached by Benjamin Woronoff, a Boston University Law student. The Fulton Club, represented by Nathan Peretzky, Harry Hoffer, and Robert Nathanson, took the Negative side in favor of maintaining the jury system. The Fultons were coached by A.C. Lurie, a Harvard Law student who formerly coached Woronoff’s team. The judges for the debate were A.C. Webber (Assistant District Attorney for the Commonwealth), Leo A. Rogers (Secretary for the Boston Police Commissioner), and attorney Solomon Lewenberg. Mitchell Freiman, the superintendent of the West End House, presided over the debate, which had 200 spectators.

None of the debaters were arguing from personal opinion; as competitors, they had the skill to prepare for arguing either side of the resolution to abolish the present jury system. After each member of the Roosevelt Club and Fulton Club spoke for or against the resolution, the judges decided which club made the more persuasive arguments. The Roosevelts, who affirmed that the present jury system should be abolished, won the debate. After the debate ended, Webber gave a brief speech “upholding the present jury system as a safeguard to justice.” The Boston Globe did not indicate how the judges voted, but this speech suggests that Webber, one of the judges, likely voted for the Fultons who were ‘upholding the present jury system.’ For the Roosevelts to have won the debate, Rogers and Lewenberg would have needed to cast the Affirmative votes, on a 2-1 decision.

Debates between literary societies previously required a unanimous vote, which changed to a majority vote by the early twentieth-century. John Adams Taylor, a public speaking and English professor at the University of North Dakota, celebrated this change in the format in a 1913 essay. Unlike the previous requirement for a unanimous vote, which held up the decision for one Yale-Princeton debate for over an hour (in Taylor’s retelling), the new method was “simpler and absolutely fair.” The judges could not be swayed by one another, and the decisions were quicker. The only flaw, in Taylor’s eyes, was that the presiding officer who read the ballots aloud could sometimes test the audience’s patience by adding suspense to their announcement:

The judges are not allowed to confer during the debate, but simply hand their sealed ballot to the usher. These are opened and read aloud by the presiding officer. Sometimes he reads the three ballots to himself before making the announcement, but it seems better to read each one as it is opened. The writer recalls one instance where the chairman announced the first ballot, ‘affirmative,’ the second, ‘negative’; and then make a few remarks before opening the third. The effect upon the audience was exasperating.

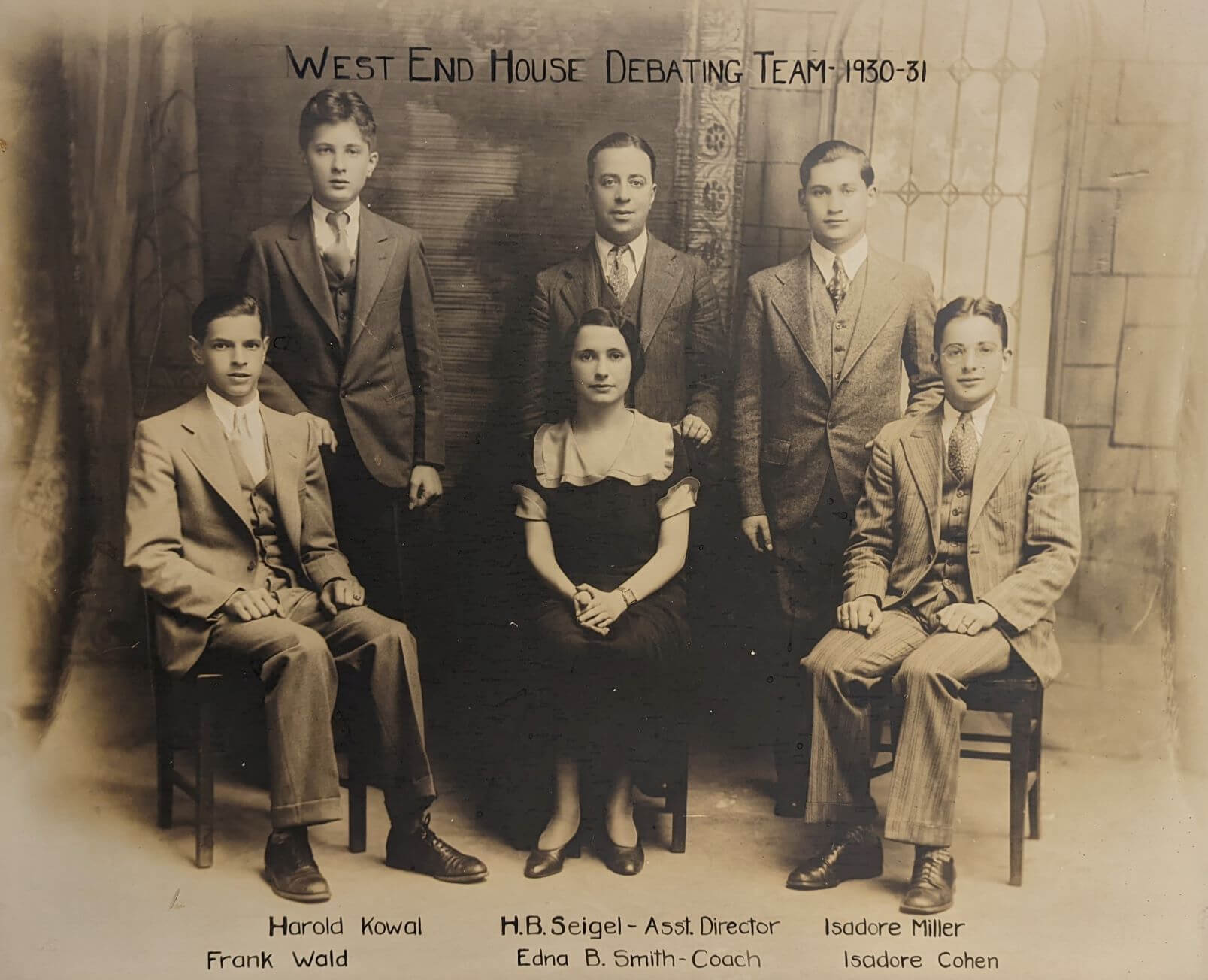

Another debate at the West End House took place the night of March 8, 1929, when the Paul Revere Associates competed against the Walter I. Cowlishaw Club on the resolution, “Resolved: That Capital Punishment Should Be Abolished In The United States.” The Cowlishaw Club, which took the Affirmative, won the debate. The judges were Frances Burnce (a teaching assistant at the Girls’ Latin School), and attorneys John P. Higgins and Harold Horvitz. Hyman Siegel, assistant director of the West End House’s “junior department,” was the presider.

The West End House, by hosting debates between high school clubs, contributed to the civic life of the historic West End by training young people to research and speak on controversial issues that mattered to the public.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Boston Globe (“Local Lines,” October 17, 1909, page 38; “Roosevelts Win: Master Defeated by One-Time Pupil in Debate on Jury System at West End House,” February 13, 1911, page 9; “Cowlishaw Club Wins Death Penalty Debate,” March 9, 1929, page 6; Adrienne Samuels, “West End Century,” May 28, 2006, B1), WEM – West End House, John Adams Taylor, “The Evolution of College Debating” (1913)