The Wild West in the West End: The Boston Garden Rodeo

In 1931, just three years after its opening, the Boston Garden hosted a new sports phenomenon sweeping the East Coast; the indoor urban rodeos of the kind produced by entrepreneur and cattleman Col. W. T. Johnson. These rodeos in the West End gave eastern sports fans a rare opportunity to relish in the romanticized cowboy image of the bygone American frontier, while also enjoying skillful, and often dangerous, feats of athleticism. Fans of these rodeos were also witnesses to the emergence of professional female sports and the birth of an organized rodeo profession.

In the early 20th century, sports fans lived vicariously through a newfound figure in the American psyche: the star athlete. Whether a heroic boxer or a hockey attacker, sports fans became drawn to events which emphasized athleticism, individualism, and ruggedness amidst an increasingly urbanized and tech-driven world. It comes as no surprise then that the rodeo garnered widespread appeal on the east coast, where the romanticized cowboy image and bygone American frontier became easily marketable. When Buffalo Bill Cody’s first Wild West Show captured the attention of the country in the 1880’s, promoters built on its success by condensing the all-day, outdoor event into a shorter, smaller competition that lasted only a few hours and could take place in urban indoor sports arenas.

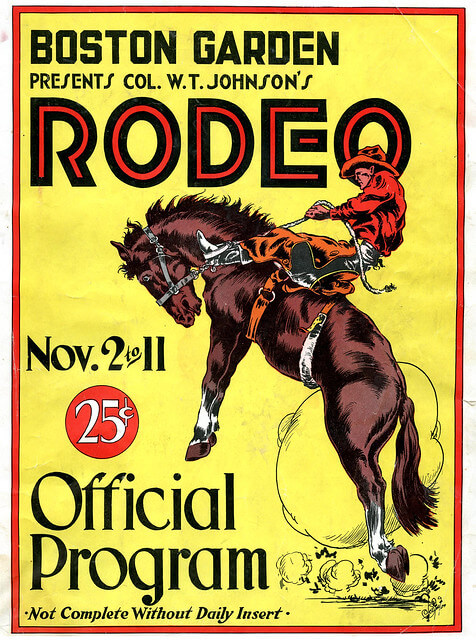

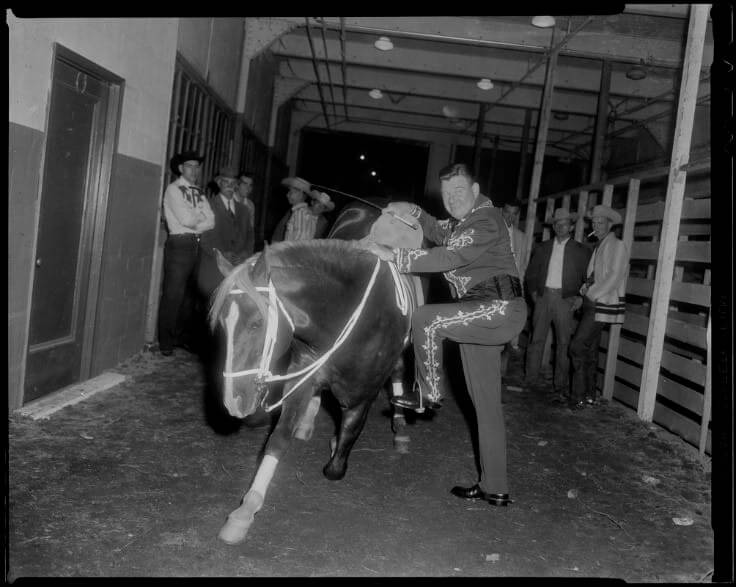

Entrepreneur and cattleman Col. W. T. Johnson became one of the top rodeo producers of his day with the abridged rodeo model. After hosting his first event in San Antonio in 1928, his showmanship soon caught the attention of the Madison Square Garden Rodeo officials from New York; by 1931, he was brought on as producer. Johnson quickly expanded and hosted his inaugural Boston Garden rodeo in November of 1931, three years after the arena opened its doors. The event set an attendance record for the stadium as 18,506 spectators descended on the West End for a glimpse of the action.

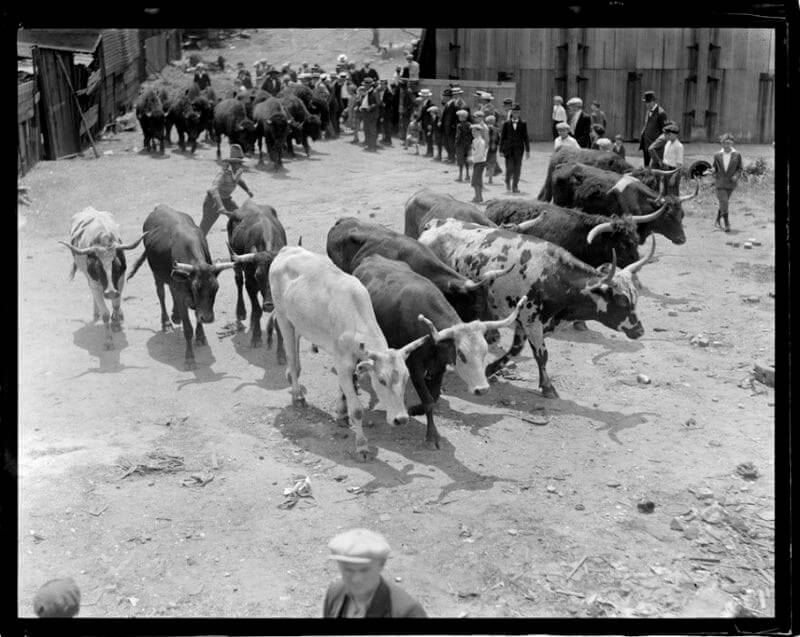

The 1931 event was Johnson’s first rodeo in the city, but the Boston audience would have been no stranger to Wild West spectacles. During the 1920s, the Oklahoma-based 101 Ranch staged several outdoor Western shows which featured authentic Texas cattle, cowhands, and other performers. During one highly publicized visit in 1922, Native American members of the 101 Ranch show traveled on horseback through the Boston streets to meet Governor Channing Cox at the Capitol Building.

While popular, it was the rise of increasingly commercialized rodeos put on by producers like Johnson that eclipsed the success of traditional Wild West Shows. Johnson had soon produced events in Detroit, Philadelphia, and Chicago as well as other locations in the Western United States. The 1931 Boston Garden rodeo was so well-received that it became an annual event, spanning a week or more each November. Even as the Great Depression plunged the country into financial turmoil, an evening at the rodeo provided several hours of escapism at a relatively low cost, and the train lines that serviced North Station enabled fans from far away to see the shows.

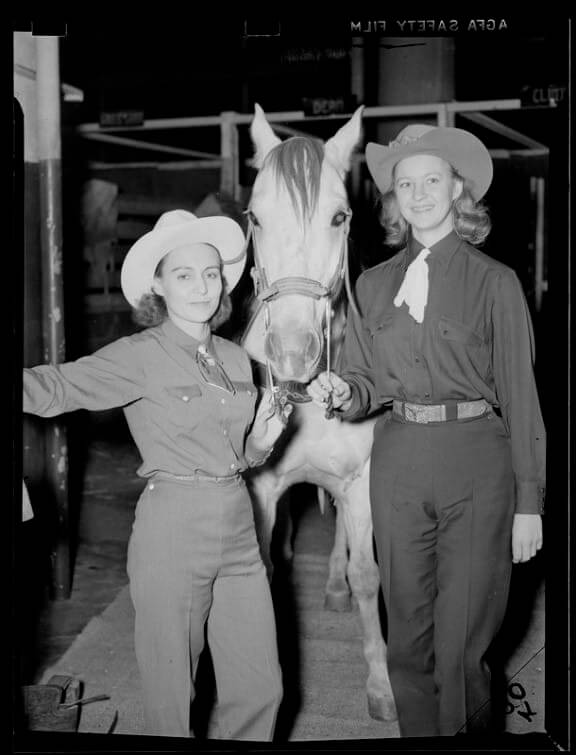

Col W. T. Johnson’s rodeos also became known for their cowgirls, who competed in events where “the same rules apply as in cowboys’ bronk [sic] riding”. The parity in rules between the men’s and women’s events was progressive in an era where women’s sports were met with suspicion. In efforts to protect women from undue danger or stress, rules were often softened, or opportunities were not offered for female competitors at all. Many rodeos had banned cowgirls outright after former Madison Square Garden champion bronc rider Bonnie McCarroll died in a riding accident in 1929.

Johnson, however, recognized the popularity of his cowgirls and continued to feature them in his shows. He even paid medical expenses for women injured during his rodeos at a time when accident insurance was not commonplace. Although championship prizes for cowboys exceeded that of their female counterparts, their presence alone was significant. The bronco-riding cowgirls, “…not inclined to admit inferiority in any line of sport, no matter how strenuous it may be,” were a remarkable example of professional female athletes less than a generation after women had earned the right to vote.

Col. W. T. Johnson’s rodeos continued to sell out arenas like Boston Garden, generating hefty revenues for the Texan entrepreneur. Performers eventually became disgruntled with their modest winnings compared to the entrance fees they paid to compete. The rodeo’s popularity added salt to the wound, as the Boston Garden paid large sums to host the event each year. The conflict boiled over on October 30, 1936, during a Friday matinee when Josie Bennett, wife of champion steer wrestler Hugh Bennett, realized the advertised prize money for all events was less than the total entrance fees Johnson charged the performers to participate in the rodeo.

Bennett alerted his fellow competitors and circulated a petition demanding that purses be doubled and entrance fees added in every event. To Johnson’s dismay, 61 performers signed the petition and staged a walk-out at the Boston Garden. After posing for the press, the striking cowboys joined the crowd in the stands as Johnson attempted to cobble together a performance using stable hands – a far cry from the champion bronc riders and rodeo veterans that were seated above the dirt-covered arena floor. With the walkout threatening not only the show that day but all future rodeos in the Boston Garden, stadium management convinced Johnson to give in to the performer’s demands.

Johnson sold his ownership share in the rodeo following the strike. Fortunately, the Boston Garden rodeo continued in the West End for decades following his departure. Today, the New England Rodeo is based in Norton, MA, 30 miles south of Boston. The success of Col. W. T. Johnson’s Boston Garden Rodeo demonstrates the importance of the Boston Garden as an economic and cultural driver for the city in the early 20th century, and signified that any kind of event – if exciting and well-marketed – could draw fans through arches lining Causeway Street and into the beloved arena.

Article by Meyer Aviles, edited by Bob Potenza

Source: University of Sheffield; Cody Yellowstone;Texas State Historical Association; Western Horseman; The Cowboys Turtle Association; Cow Girl; “Record-setting attendance at the Garden,” Boston Globe,1931.

1 Comment