Thomas Edison: The Inventor’s Time in Boston

Thomas Edison (1847-1931), the famed inventor with 1,093 patents, got his start in Boston before contributing to the invention of the lightbulb, phonograph, and movie camera. From staying at boarding houses on Cambridge Street to experimenting in workshops in Scollay Square, the West End was a launching pad for the young Edison’s nascent career as an inventor and entrepreneur.

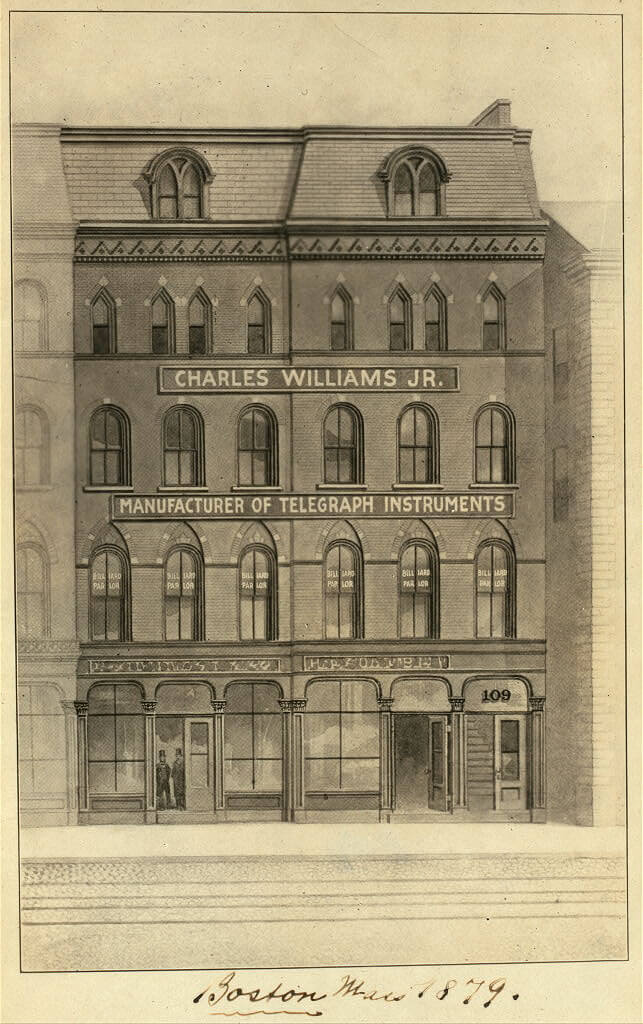

Thomas Edison moved from Port Huron, Michigan to Boston in early 1868. Edison was only twenty-one at the time but, during the next year and a half that he would spend in Boston, he was provided with vital resources and funding that allowed him to become an inventor, manufacturer, and entrepreneur. When Edison arrived, Boston was already a hub for telegraph technology and was one of the largest cities in the United States, hovering around 200,000 people. In the 1860s, Boston had two telegraph companies and hundreds of operators. The two major telegraph companies were the Western Union Telegraph Company (four offices in Boston) and the Franklin Telegraph Company (three offices in Boston). In addition to those two operations, there were two key telegraph manufacturers, Charles Williams Jr., and Edmands and Hamblet.

In March 1868, Edison penned a letter to his friend Milton Adams, a telegraph operator in Boston working for Western Union, expressing his desire to move to Boston. Adams, recognizing the potential in Edison’s unique penmanship and creative flair, connected him with George Milliken, the renowned telegraph inventor and owner of Western Union. This introduction led to a five-minute interview, during which Milliken was so impressed with Edison’s skills that he offered him a position as a telegraph operator on the spot, specifically as a receiver on the press wire from NYC “Number 1 Wire.”

The 1868 Boston City Directory gives Edison’s address as 4 Bulfinch Street, and the 1869 Directory gives his business address as 9 Wilson Lane. Other correspondents and people who worked at Western Union remembered him and Adams living together at Exeter Place and at 44 Cambridge Street, locations of boarding houses.

Boarding Houses in 19th-century Boston were essential hubs for young professionals and traveling workers like Edison. These houses offered affordable accommodations, meals, and the chance to network with diverse residents. In the 19th century, 30 to 50 percent of Urban Residents lived in such houses. Boston had 583 boarding houses in 1860, primarily in the West End and South End. For Edison, boarding houses were more than just a place to live; they were vibrant communities that facilitated his inventive ideas. In these communal spaces, surrounded by other young professionals, Edison was surrounded by potential collaborators and investors. Also, living in these boarding houses allowed Edison to focus on his work at Western Union and his experiments without the labor of managing a household. Ultimately, the communal nature of these houses was essential in Edison’s early success.

At Western Union, Edison’s ability to swiftly and accurately handle telegraph operations impressed his peers and superiors. He also devoted much of his time to visiting Boston’s many telegraph shops to spend time with other telegraph experimenters and inventors. Edison soon started to do his own experimental work at Charles Williams’ shop at 109 Court Street in Scollay Square, where electrical inventor Moses Farmer had a laboratory.

Stories of Edison from this period characterize him as the office eccentric who would tinker around when working the night shift. He was known as an amusing figure both in the office and the West End neighborhood. In one instance, Edison rid the office of cockroaches using tinfoil and wire by unrolling tinfoil, stretching it around a table, and connecting the foil to two heavy batteries. As soon as the cockroaches crawled over it, they were shocked. By lunchtime, they had to brush dead insects to the floor, and by midnight, the floor was covered in dead beetles.

Edison’s reputation as a scientist quickly grew in Boston, despite his sometimes erratic behavior, leading him to lecture at well-known academies. During one memorable lecture at an upper-class women’s academy, Edison arrived over an hour late – he had lost track of time because he had been performing acrobatic feats on top of a high-up telegraph wire.

While living in Boston, Milton Adams was always at Edison’s side, and the two were frequently spotted visiting old bookstores. One day, as Adams recounted, Edison bought Michael Faraday’s entire works on electricity. Edison stayed up all night reading all of Faraday’s books. As the pair went to breakfast the following day, Edison, eyes bright with determination, said: “Adams, I have got so much to do, and life is so short that I am going to hustle.”

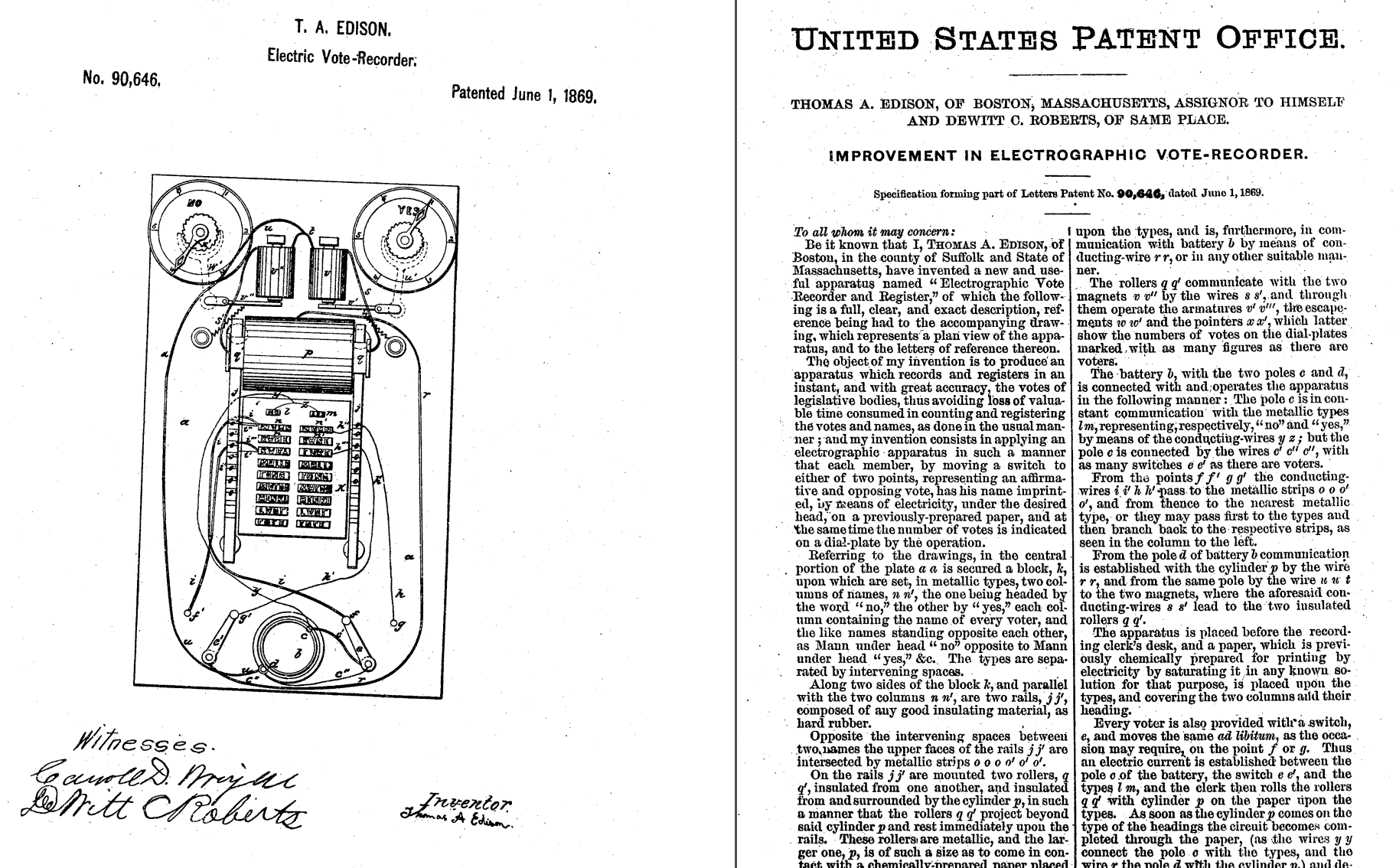

While in Boston, Edison submitted his first two patents – he would be granted 1,093 throughout his lifetime. His experiments were supported and funded by wealthy Bostonians, including Dewit Roberts, E. Baker Welch, and John Lane.

In October 1868, Edison submitted his first patent application for an electric vote recorder for legislative bodies. The machine used electricity to imprint names under “yes” and “no” labels on a sheet of paper and also displayed the number of votes on a dial plate. The invention was complex, utilizing multiple switches, types, rollers, strips, magnets, and batteries. The voter would move a switch to place their vote; then, by rolling a cylinder over the types, names were printed, and votes were counted with relative precision and speed. Edison, who himself had read many press reports about how long it took to count votes, believed that this electric voting system would be both more efficient and less easily manipulated. He was issued U. S. Patent 90,646 on June 1, 1869.

However, his trip to Washington, D.C, to demonstrate the invention did not turn out as he hoped. At one D.C. meeting, the Chairman of Committees said to Edison: “Young man, it works all right and couldn’t be better… But it won’t do. In fact, it’s the last thing on earth that we want here. Filibustering and delay in counting of the votes are often the only means we have for defeating bad legislation… Take the thing away.” In the end, his vote recorder was never used.

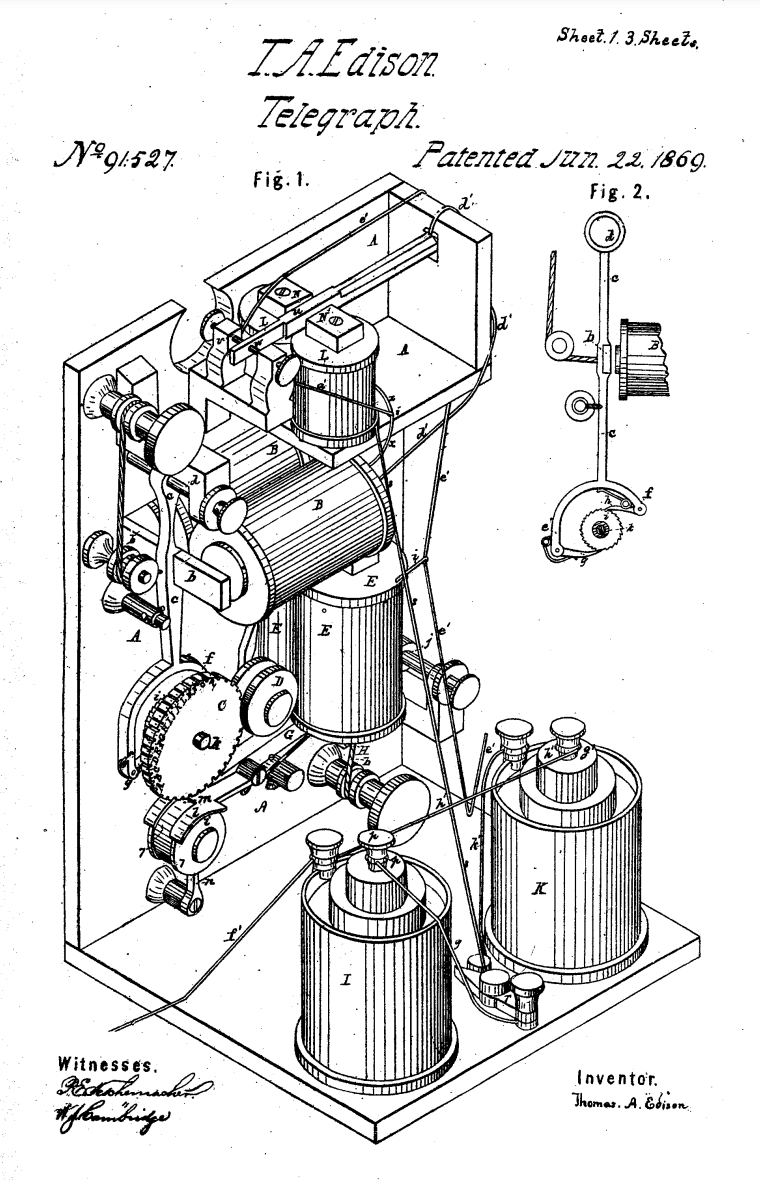

His next invention, patented June 22, 1869, was an improvement in printing telegraphs. Edison aimed to create a simple, inexpensive, and reliable printing telegraph that operated without an attendant at the receiving station. The invention consisted of two electro-magnets within the same circuit – one for making the type-wheel rotate and the other for putting the printing hammer into action – and a polarized relay that worked as an automatic switch to determine the direction of the current and control which magnet was activated. This innovation removed the need for a battery at the receiving station, as the transmitting station’s battery powered every mechanism.

Timeline of Edison in Boston

- March/April 1868 – Edison moves to Boston to live with Milton Adams and begins working as an operator at Western Union.

- April 11, 1868 – Edison publishes a newspaper article in the Telegrapher, focused on telegraph inventions and on the technological advancements made by the Boston Telegraph Community.

- July 11, 1868 – Edison receives his first financing for his inventions from Boston businessman E. Baker Welch.

- July 28, 1868 – Edison assigns his first invention to Welch, a fire alarm telegraph system.

- October 13, 1868 – Edison signs a patent for an electric vote recorder, and later issues it as his first patent.

- January 21, 1869 – Edison sells the rights to the first printing telegraph (which he calls “The Boston Instrument”) to two prominent Boston businessmen, William Plummer and Joel Hills.

- January 30, 1869 – Edison resigns from Western Union to pursue inventing full-time.

- January-April, 1869 – Edison joins Frank Hanaford in establishing a business to produce and sell private line telegraphs at a shop at 9 Wilson Lane.

- May 1869 – Edison moves to New York City.

Article by Kegan Foley, edited by Grace Clipson.

Source: “Boston Inventor and Businessman: 1868-1869,” Thomas A. Edison Papers; Thomas Edison, Electric Vote-Recorder, U.S. Patent, 90,646, issued June 1, 1869; Thomas Edison, T.A. Edison Telegraph. U.S. Patent, 91,527, issued June 22, 1869; Reese V. Jenkins, The Papers of Thomas A. Edison: The Making of an Inventor, February 1847-June 1873 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1989); Francis Arthur Jones, Thomas Alva Edison, Sixty Years of an Inventor’s Life (New York, New York: Cromwell & Co., 1907); Kenneth R. Manning, “The Culture of Invention in Boston,” Thomas A. Edison Papers (Rutgers: The State University of New Jersey, January 1995); The West End Museum, Boarding Houses in the West End.