Charles River Park

Charles River Park is an apartment complex built on 45 acres of the historic West End, soon after its demolition. Jerome Rappaport, Sr., attorney for Charles River Park, Inc. and one of the corporation’s early investors, was politically connected to Mayor John Hynes, whose platform for a “New Boston” was the pretext for urban renewal. The vast majority of West Enders could not afford the luxury apartments that replaced their homes. The first tenants of Charles River Park were offered many modern, communal amenities – intended to attract young professionals and suburban families alike.

In November 1956, the Boston Housing Authority awarded Charles River Park, Inc. the rights to redevelop the fifty acres of Boston’s West End slated for demolition. Two of the principal shareholders of the Charles River Park corporation were Theodore Shoolman, whose father, Max, was a developer who previously worked in the West End, and Seon Pierre Bonan, who owned the Bonwit Construction Company. The third principal shareholder – and the most famous of the three – was Jerome Rappaport, Sr., the Harvard-educated lawyer who also served as Charles River Park’s attorney. Rappaport had previously served in the administration of Mayor John Hynes, whose platform for a “New Boston” culminated in urban renewal in the West End. The contract for redevelopment of the West End was originally up for public auction, yet Kane Simonian – the first director of the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA) established in 1957 – called off the auction and awarded the contract to the firm connected to Rappaport. The possibility that political favoritism played a role in Simonian’s decision was not lost on West Enders and their political allies critical of the lack of transparency. Simonian defended his decision on the basis that a “sealed-bid” competition was sufficient to choose the best developer, and that rents may have been too costly had the land been up for auction. Charles River Park had the highest of five bids, purchasing the land of the urban renewal zone at a price of $1.5 million.

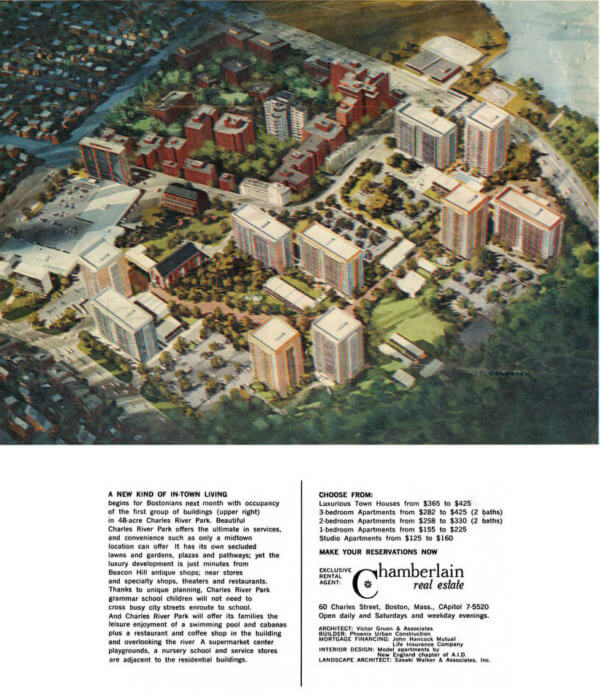

The BRA began its demolition of the West End in 1958, and the planning for Charles River Park took shape soon after. Shoolman, Bonan, and Rappaport hoped that the development of Charles River Park would encourage post-World War II suburbanites to move back to Boston. The developers purposely included multiple two-and-three-bedroom apartments to attract families and young people to the new apartment complex. Charles River Park, Inc. selected world-renowned architect Victor Gruen to revise the city’s initial plan for the project. Gruen, known as “the father of the shopping mall,” envisioned a series of towers connected by green spaces, and side roads that separated those towers from the rest of the city.

In 1959, Victor Gruen Associates finished a blueprint for a $55 million, 45 acre development for 2,400 apartments split into five “neighborhoods,” developed one at a time over multiple years. The Gruen plan received an award from Progressive Architecture magazine, and early reporting on Charles River Park described it as less of a typical apartment complex and more of a “community.” Cyrus Smith, a project manager for Phoenix-Urban Construction Company, was in charge of the construction.

In 1959, A.S. Plotkin of the Boston Globe commented on the last West Enders who would remain as Charles River Park gradually replaced the historic neighborhood:

Several years will elapse before all five ‘neighborhoods’ are finished. Thus, some original West Enders will still be living out their last days in the crowded doomed old area even while others will have already moved into tower suites which are ultra modern and air conditioned.

The above comparison reinforced that the luxury apartments of Charles River Park were largely unaffordable for displaced West Enders. Once Charles River Park, Inc. received the redevelopment contract in 1956, the city had abandoned its original promises to West Enders that they would be able to return to their neighborhood with affordable housing. But the mass displacement produced by urban renewal was overshadowed in the press by glowing reports of the amenities of Charles River Park: community gatherings, air conditioning, and the possibility to commute and shop without needing a car (unlike in the suburbs). In November of 1961, the first tenants of Charles River Park moved in, and by by May of 1962 over 350 families lived in the development.

Other amenities offered to tenants by 1965 included a “Pool and Cabana Club” with a “larger than Olympic-sized” swimming pool, and an on-site nursery school (open to non-residents, who comprised the majority of the children attending). The Charles River Park complex also included its own drug store, small grocery store, dry cleaner, liquor store, restaurant, and beauty salon. A spokesperson for Charles River Park commented that it was on its way to becoming its own “total in-town community.” In 1967, Charles River Park introduced smokeless incinerators so that residents’ trash could be burned with virtually no air pollution. By 1970, Charles River Park had its own health club with gym equipment, a ping pong table, and a women’s lounge with hair dryers. All of these amenities, from green spaces to every conceivable modern comfort, were intended to create a residential community that blended the city with the country (in the lofty language of early reporting).

The relationship between Charles River Park and the BRA was not always cooperative. In 1967, Charles River Park, Inc. requested that the BRA cease its development of new parking lots in the urban renewal zone of the West End. The company argued that the lots would cut into their own plans to build parking garages for Charles River Park residents. They also claimed, in the words of one report, that “the lots, run by a private operator, are a blighting influence on a modern apartment building recently finished under the renewal plan.” By 1970, Charles River Park had not yet developed the apartments they promised on a 10-acre site near Government Center, the last undeveloped land in the urban renewal area. The company was criticized for letting the land go to waste as, ironically, a “mud-rutted, debris-strewn parking lot.” An unnamed opinion writer for the Boston Globe argued that the parking lot reflected wasteful spending of urban renewal funding and foot-dragging by Charles River Park and the BRA. The writer’s conclusion: “The West End renewal has involved one disgraceful delay after another since 1958. It is time the BRA closed this final chapter by whatever means.” Ultimately, the activism of renewal-displaced West Enders was instrumental in compelling the BRA to take control of this last undeveloped parcel – the “final chapter” – for development of West End Place, a the mixed-income building opened in 1997.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Society of Architectural Historians; The West End Museum; Commonwealth; ProQuest/Boston Globe (Wilfred Rodgers, “Charles River Park Builders All Young: West End for Disillusioned Suburbanites,” February 7, 1960; A.S. Plotkin, “West End Development, Another Boston New Look,” March 12, 1959; “Charles River Park deadline,” June 12, 1970; “Smokeless Incinerators for Charles River Park,” November 26, 1967; “ ‘Something Different…’ At Charles River Park,” June 20, 1965; “Charles River Park wins Supreme Court go-ahead,” November 16, 1972; “Charles River Park, Inc. Buys Land for $640,000,” February 7, 1965; Anthony Yudis, “B.R.A., Charles River Park At Odds Over Parking Lots,” December 1, 1967).