The Catholic Church and the Destruction of Boston’s West End

The Catholic Church was more than a religious institution in 20th century Boston. It was a land holder as well as a facilitator and participant in urban renewal. The Church’s role raises questions on accountability and how powerful institutions can abandon the people who put their faith and trust in them.

Introduction

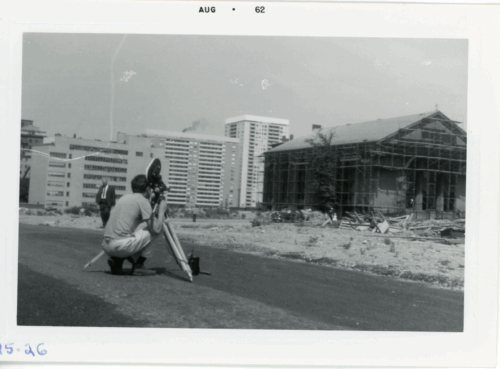

In the mid-20th century, Boston’s West End was razed under the banner of urban renewal. The city used federal funds to modernize Boston by clearing “urban blight”. The West End was once a vibrant, working-class neighborhood filled with immigrant families. Urban renewal replaced the neighborhood with luxury towers and civic buildings. Among the institutions deeply embedded in the life of the neighborhood was the Catholic Church. The Church played a complex and sometimes controversial role in this transformation.

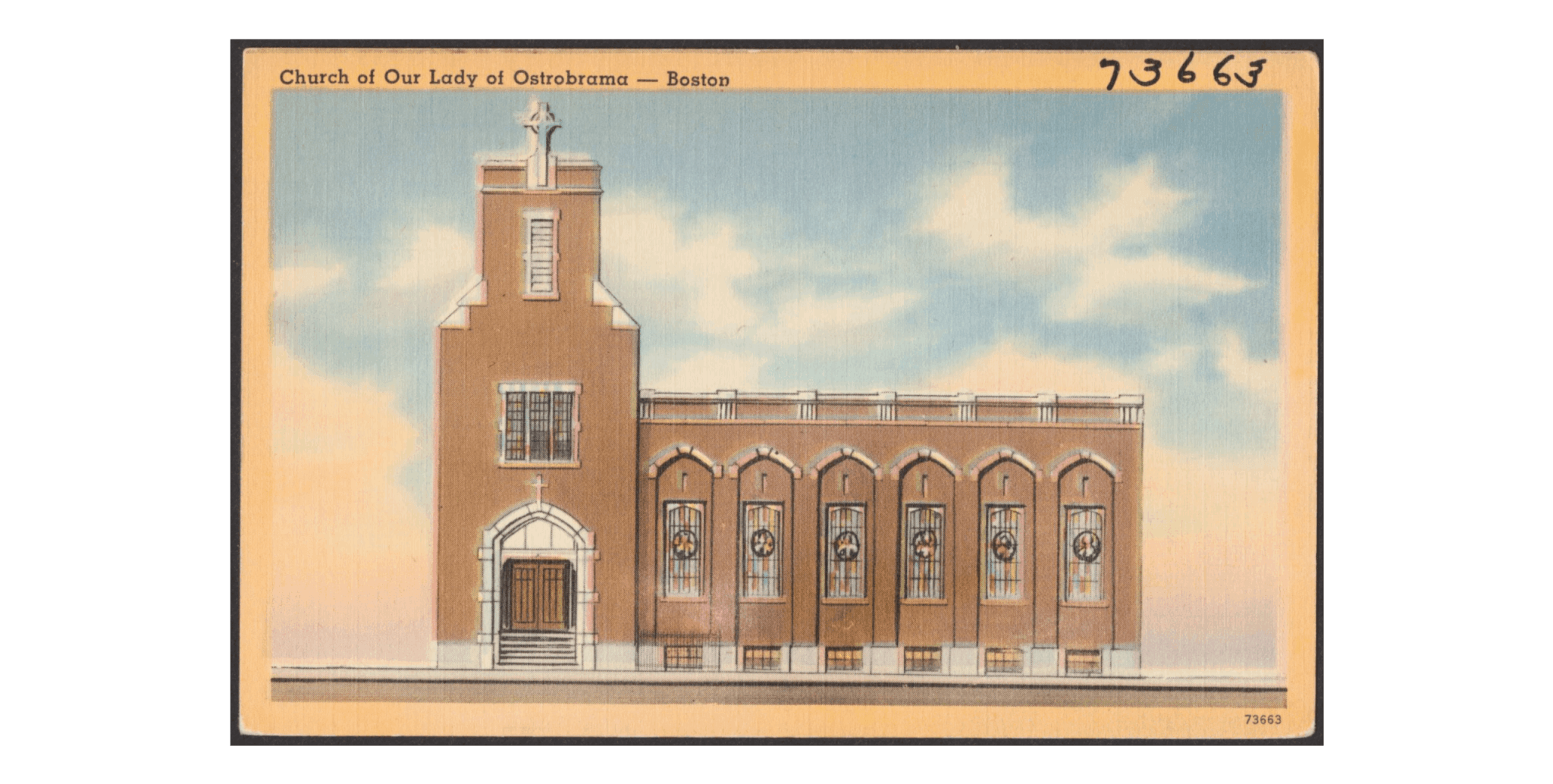

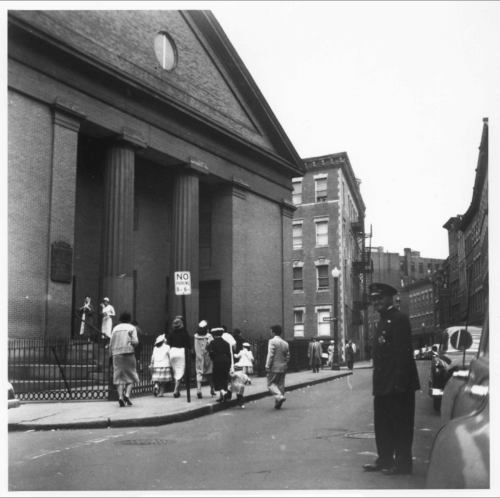

The West End was the location of Boston’s first Catholic mass in 1788. By the 1950s, it was home to a large Roman Catholic population served by two major parishes: St. Joseph’s and Our Lady of Ostrobrama, a Polish Catholic church. Before its demolition, the West End housed over 12,000 residents. They were mostly immigrants from Italy, Ireland, Poland, and Russia. It was a neighborhood of tenements, corner stores, and strong social ties. Catholic parishes like St. Joseph’s Church served as spiritual and communal anchors. They offered not only religious services, but also a sense of belonging and stability. St. Joseph’s also ran an associated parochial school.

Despite its vitality, city officials labeled the West End “blighted” and a slum, citing overcrowding and aging infrastructure. These assessments ignored the neighborhood’s cultural richness and community cohesion. The Boston Housing Authority, and later the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), proposed a sweeping clearance plan. They would erase the neighborhood and replace it with a modern hi-rise development named Charles River Park. The leadership of the Catholic Archdiocese of Boston was deeply involved in this process.

Urban Renewal and the Church’s Position

Boston’s Catholic Church, led by Richard Cushing, the Cardinal-Archbishop of Boston, was a powerful institution. Under Cushing’s leadership, the number of Catholic parishes reached its peak of over 400 in the mid-1960s. The Church had deep ties to immigrant communities and extensive real estate holdings. They had both moral and material stakes in urban renewal. Cushing supported both the redevelopment of the West End and Government Center. Additionally a priest, Monsignor Francis J. Lally, served as the chairman of board of the BRA.

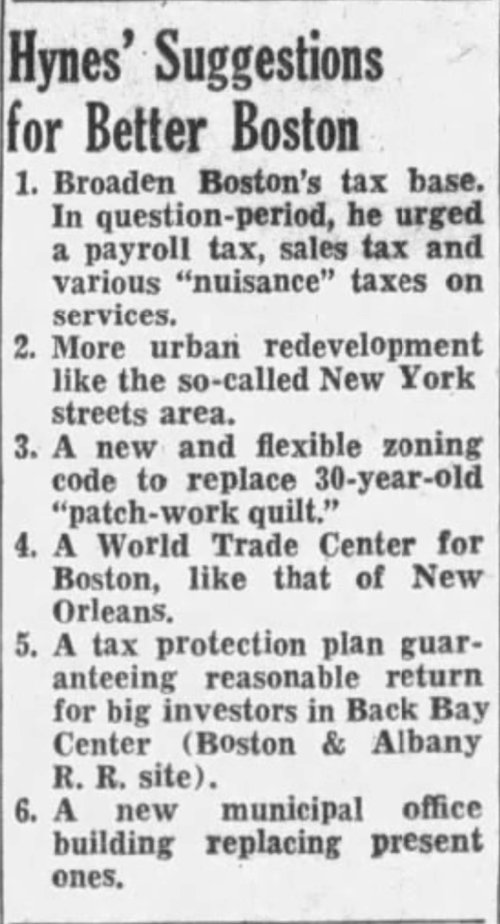

Between the announcement of the West End Project in 1953 and the beginning of demolition in 1958, officials discussed the neighborhood’s destruction. A seminar series that kicked off on October 26, 1954 brought many of the area’s redevelopment decision makers to the table. Reverend Seavey Joyce, dean of the College of Business Administration at Boston College convened “A Citizens’ Seminar on the Fiscal, Economic, and Political Problems of Boston.” The seminar brought together over 100 of the city’s business, labor, industry, and political leaders. There was little to no representation of everyday citizens – those who would be most affected by urban renewal. The first speaker, Mayor John Hynes, was in favor of more urban redevelopment. In his speech, he mentioned the upcoming urban renewal project in the South End’s New York Streets. This project would displace over 1,000 people the following year. Yet, Mayor Hynes had already had his sights on a grander vision. “We have other areas in our city in mind,” he said. The New York Streets urban renewal project was a small, experimental predecessor to the West End’s larger and more impactful project.

The Church did not publicly oppose the demolition of the West End. Its silence was notable. The institutional Church aligned with the city’s modernization goals. At the same time, thousands of its parishioners faced displacement. This hypocritical position reflected a tension between the Church’s pastoral mission and its institutional, and financial, interests.

The Church’s lack of resistance was deeply felt. For many, parishes like St. Joseph’s were more than places of worship—they were lifelines and communities. The loss of these institutions would compound the trauma of displacement and leave a lasting sense of betrayal among former residents. Poignantly, St. Joseph’s Church was one of the few buildings spared the wrecking ball, though its parishioners scattered to the wind. St. Joseph’s was exempted from demolition since it was where William O’Connell, the first archbishop of Boston to become a cardinal, began his career. In the years after urban renewal, St. Joseph’s stood alone in a sea of rubble that had once been a beloved neighborhood.

Institutions like the Church were caught between ideals and realities. The Church’s support for renewal reflected its desire to remain influential in a changing city, but it also exposed the limits of its commitment to the communities it served.

Displacement and Broken Promises

In 1958, residents of the West End began receiving eviction notices. In earlier plans, the BRA promised that displaced families would have “first preference” in the new housing, but this promise was not fulfilled. The only residential buildings constructed in the West End over the next fifteen years were luxury apartments, unaffordable to former residents. By 1970, the neighborhood’s population had dropped to around 2,000. This was down 12,000 people from the population at the time of the project’s announcement.

Despite the physical destruction of the West End, its memory endured. Former residents continued to gather for annual masses at St. Joseph’s Church, even after their displacement.. These acts of remembrance became symbols of resilience and resistance. In later years, St. Joseph’s became a place for former West Enders to gather for reunions. It never formally apologized for its role. The Catholic Church’s participation in the urban renewal process reflected its broader struggle to balance moral authority with political influence. The Church’s complicity in the clearance is a reminder that institutions must be accountable—not only for what they build, but for what they allow to be destroyed.

Article by Daniel Spiess, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Archdiocese of Boston, “History of the Archdiocese of Boston”; Boston Globe, “Boston’s Ills to be Aired at BC Seminar Series,” October 8, 1954, “BC Opens Seminars on Boston Problems,” October 24, 1954, “Mayor Hynes’ Ideas: Boston Can Join World’s 1st Cities by 5-Point Plan,” October 27, 1954; Lizabeth Cohen, Saving America’s Cities: Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age, (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2019); Jule Pattison-Gordon, “How Urban Renewal Shaped Boston,” Bay State Banner, March 31, 2016; Saint Joseph Parish, “History of St. Joseph Parish”; The West Ender Newsletter, Volume 15, No, 1 (March 1999).