West End Brutalism

Boston’s brutalist buildings are divisive, having inspired decades of both contempt and praise. The Government Center Project and its brutalist structures are the result of, and symbols of, debates surrounding urban renewal planning in the 1950s and ‘60s. The divergence in opinions between architectural and political elites and ordinary people is illustrative of larger issues and trends related to the Urban Renewal and New Boston movements.

One of the world’s most famous examples of brutalist architecture is Boston’s City Hall, a hulking concrete structure whose bold form stands in contrast to the city’s traditional architecture. Notorious for its unconventional style, City Hall has prompted powerful reactions from the public. Detractors disparage City Hall as an oppressive eyesore, but admirers value its commanding presence.

Not far from City Hall and situated in Boston’s West End, Government Service Center is a complex that includes two additional brutalist buildings: the Charles F. Hurley Building and the Erich Lindemann Building. Like City Hall, Government Service Center has garnered mixed reactions from a wary public. Yet, the powerful reactions inspired by City Hall and Government Service Center often overshadow their historical importance. The West End’s brutalist buildings recount a significant moment of transformation in the city’s history and speak to the potential of architecture to redefine an American metropolis.

The story of these buildings begins at a low point in Boston’s history. When Mayor John Collins took office in January 1960, the city was faced with massive challenges. High property taxes had driven out investors, the construction of new buildings had slowed, and suspicion of the local government was growing in the wake of corruption scandals. Weary of the city’s economic troubles, middle-class Bostonians were fleeing. According to Lizabeth Cohen, Boston lost eight percent of its jobs and thirteen percent of its population in the decade following 1950.

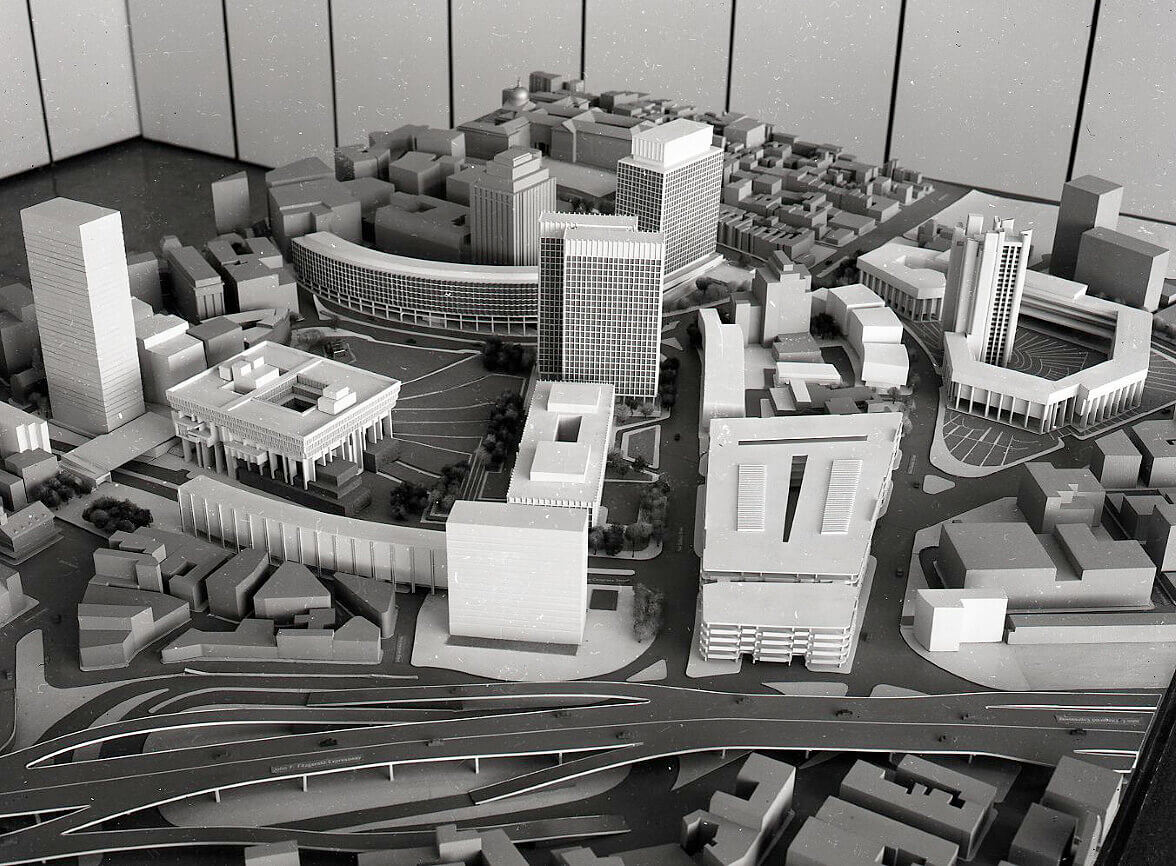

Boston’s new mayor had plans to reverse these trends. Pursuing an initiative first devised by his predecessor, John B. Hynes, Collins set out to create a new government center that would spark investment and spur development. The new center would be a nexus for commerce and government affairs, housing employment, health, education, and welfare offices. Architect I.M. Pei was commissioned to oversee the masterplan for the new complex. He modeled Government Center after an Italian piazza. It was designed to allow citizens to witness governmental operations so that Boston could recoup its reputation as an epicenter for democratic values. The complex would boast monumental contemporary buildings and mark Boston as dynamic and forward-looking.

To advance his ambitious architectural project, Mayor Collins turned to the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA). Established in 1957, the BRA had a contentious history, having overseen an earlier Urban Renewal program that razed 50 acres of West End neighborhood, displacing over 12,000 people. The blunders of the BRA’s program were fresh in the minds of officials. Collins knew that many citizens felt betrayed by their government and he, together with Ed Logue, the newly appointed head of the BRA, promised that their development plan would be created in consultation with community members. Despite these assurances, the Government Center project was met with protests against the destruction of Scollay Square, a vibrant entertainment district.

Collins moved forward with his plan. On October 16, 1961, a competition was announced soliciting proposals to build Boston’s new City Hall. The competition garnered 256 entries from architects all over the country. Out of these, a jury selected a design by Gerhard M. Kallmann, N. Michael McKinnell, and Edward F. Knowles. Their entry imagined City Hall as a massive structure constructed from raw concrete. Made of hefty, seemingly indestructible materials, City Hall would embody the virtues of a robust government working for its citizens.

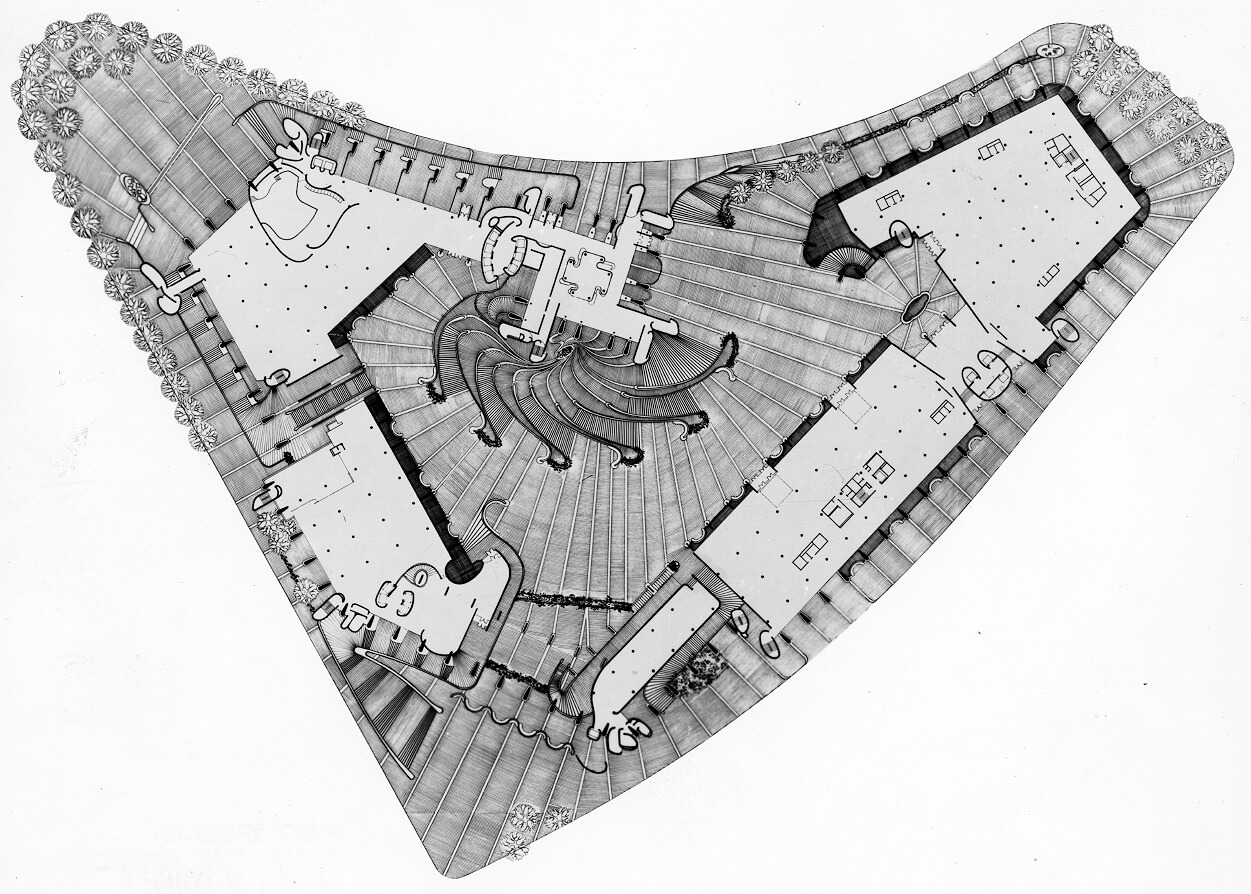

Architect Paul Rudolph, meanwhile, was charged with developing a plan for Government Service Center. Though Rudolph never used the term himself, his plan’s architectural style became known as brutalism. Rudolph’s design included “corduroy” (corrugated) concrete and an amphitheater-esque format filled with curvilinear shapes. The plaza was packed with irregular forms, inspired by the irregular street patterns of Boston. In describing his idea process, Rudolph said: “I wanted to hollow out a concavity at the bottom of Beacon Hill, a spiraling space like a conch in negative relation to the convex dome of the State Capitol on top of the hill.”

Characterized by angular forms, deep-set windows, and slabs of unadorned concrete, brutalist architecture was first “an ethic, not an aesthetic,” as critic Reyner Banham suggested in 1966. In part a response to the privations of WWII and in part a result of newfound interest in architectural frankness, brutalist architecture was expressive and aspirational. Raw concrete conveyed honesty and integrity, ideals important for a government attempting to shed its reputation for malfeasance. Cohen explains that for Boston City Hall “the choice of brut concrete… [embodied] democratic ideals…concrete seemed authentic and honest.” Because it was a mundane material, concrete signaled humility and an absence of pretense—the very attributes Boston’s local government was seeking.

City Hall and Government Service Center distanced themselves symbolically from the corrupt politics of the past. Without ornamentation, these brutalist structures were the antithesis of traditional public administrative buildings, which Cohen notes, “were constructed in brick and stone and decorated with classical motifs—columns, carvings, and other ornamentation—meant to invoke the grandeur and long legacy of republican government.” Discarding formal elements of traditional governmental buildings, these structures distinguished themselves from the nefarious habits of previous administrations. The ornamented facades of traditional municipal buildings were associated with obfuscation and corruption, while the plain facades of brutalist buildings represented truth and transparency.

Boston City Hall opened to the public in 1969 under a new mayor, Kevin H. White. Government Service Center opened to the public two years later, in 1971. Upon the buildings’ openings, professional architectural critics lauded City Hall as a masterpiece. A Boston Globe review praised the building’s forward-thinking design as “nothing but a wholehearted affirmation of a new time, new social needs and the new technology and new aesthetics to declare faith in the civic instrument of government.”

Though they were the darlings of professional architectural critics, these brutalist buildings failed to win over many ordinary citizens. A large portion of the general public saw the concrete behemoths as overbearing and stark, metaphors for governmental hubris. Additionally, Rudolph’s symbolic design proved to be convoluted and dangerous in practice: his open stairwells, rough surfaces, and labyrinthine format were in many ways unsuitable for a mental health services complex.

City Hall is regularly named one of the “ugliest” buildings in the world. Detested by a public who sees these buildings as unattractive, the fate of these brutalist structures remains uncertain. In 2007, Boston Mayor Thomas M. Menino called for the demolition or sale of City Hall. While City Hall still stands, another structure in the complex, Government Center Garage met its end. Today, Government Center’s brutalist buildings are said to suffer from “active neglect.”

In spite of these obstacles, admirers are making efforts to revive brutalism—physically and reputationally. Online campaigns like “SOS Brutalism” have emerged to save brutalist buildings by apprising advocates of buildings in danger of demolition. Likewise, architects and scholars Mark Pasnik, Michael Kubo, and Chris Grimley have called for a reassessment of the term “brutalism,” arguing that brutalist architecture has been disparaged and misunderstood due to the term’s negative connotations. They suggest the term “heroic” more accurately captures the philosophy and style of these buildings.

Boston’s brutalist buildings are divisive, having inspired decades of contempt and praise. They should also inspire reflection. Boston’s brutalist buildings embody a transformative moment in the city’s history, and they speak to the power of architecture as a tool for reinvention. Throughout urban renewal programs in the 1950s and ‘60s, architects and planners saw brutalism as an appropriate architectural language, the visual counterpart to the rhetoric of “renewal” and “New Boston.” While the architectural and political elite saw these structures as an image of strength and redevelopment, most normal Bostonians felt alienated and enraged. The Boston Government Service Center stands as a reminder of these debates, and the complicated legacy of urban renewal.

Article by Elizabeth Lambert, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Lizabeth Cohen, Saving America’s Cities: Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age (Picador, 2020); Lizabeth Cohen, “Building Government Center: The Boston Redevelopment Authority. 1960-67” in Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston (The Monacelli Press, 2015); Thomas H. O’Conner, Building a New Boston: Politics and Urban Renewal, 1950-1970 (Northeastern University Press, 1995); Mark Pasnik, Michael Kubo, and Chris Grimley, Heroic: Concrete Architecture and the New Boston (The Monacelli Press, 2015); The Paul Rudolph Institute for Modern Architecture, “Boston Government Service Center.”