Boston’s Original West Church: A Revolutionary Meetinghouse

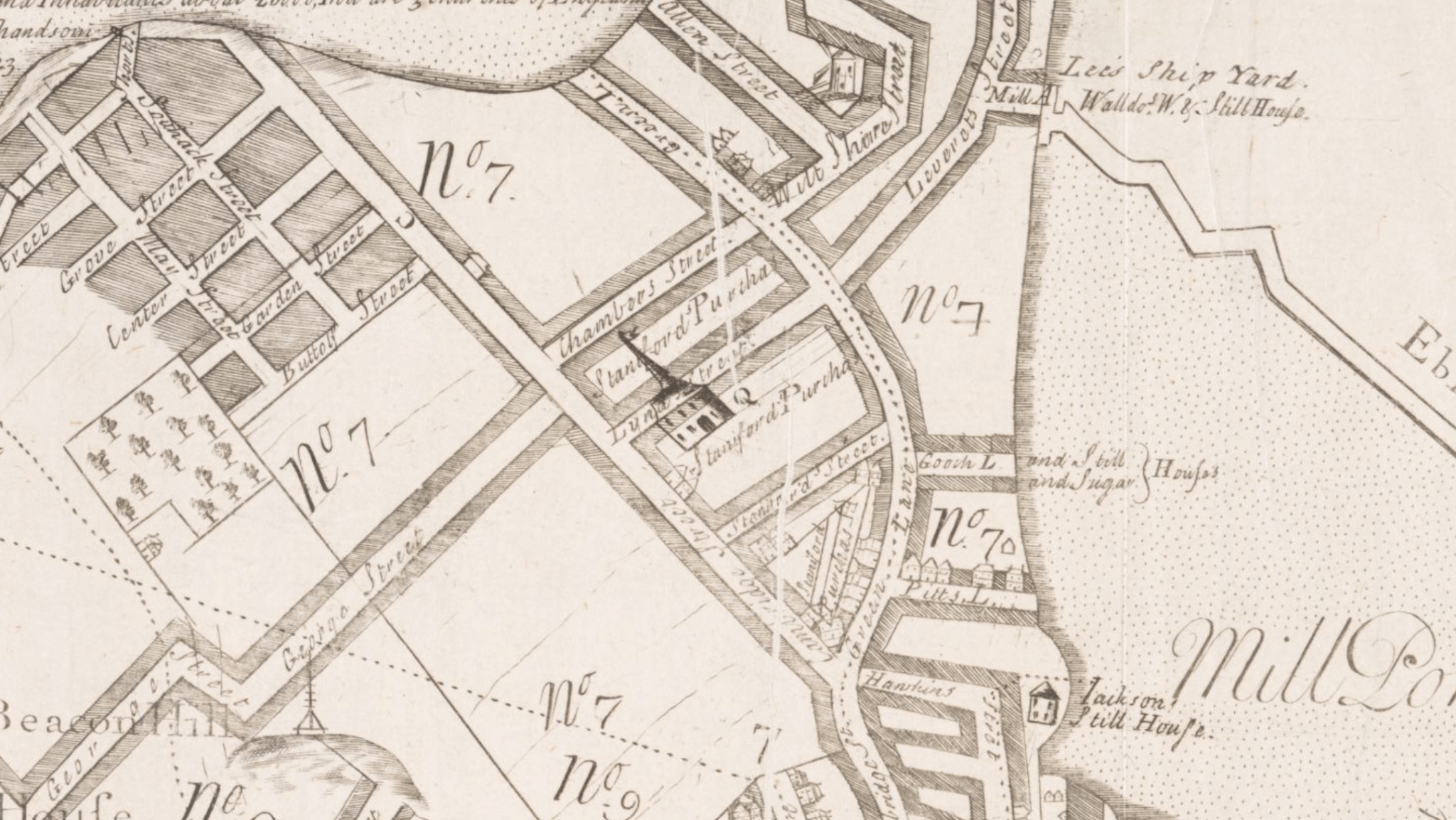

The original West Church, a wood-framed structure erected in 1737 at the corner of Cambridge and Lynde Streets, played a significant role in Revolutionary-era Boston. At this site, minister Jonathan Mayhew preached for civil liberties and resistance to tyranny, influencing prominent patriots such as John Adams and Paul Revere. The church was used as barracks by British troops during their occupation of the city and its steeple was destroyed by British forces in 1775. Severely damaged during the Revolutionary War, the original West Church was taken down and the current Old West Church was built in 1806.

The Old West Church on Cambridge Street, built in 1806, stands today as an iconic landmark in the neighborhood, and one of the finest standing examples of Asher Benjamin’s Federal style architecture. This nineteenth-century church, however, was not the first West Church to stand on the site at the corner of Cambridge Street and (then) Lynde Street: the original West Church was built here in 1737 as a wood-frame building, remaining there until it was replaced by the current Old West Church.

In the first two decades of the eighteenth century, West Boston (or New Fields) remained relatively pastoral, containing not much more than a textile mill, early rope-making facilities, a windmill, and copperworks. Around 1720, this situation began to change, as people moved from the congested North End to build residences in West Boston. From this grew demand for a neighborhood church. A group led by Hugh Hall (a wealthy merchant and enslaver) and Harrison Gray (also a wealthy merchant and future Treasurer and Receiver-General for the Province of Massachusetts Bay) spearheaded this effort to erect a place of worship. Others soon joined to help found the new congregation. One entry from The Records of the First Church of Boston notes that on December 26, 1736, three of their members left to join the new West Church: “James Gooch junior, John Darrell, and John Daniel, [left] to the new Society about to embody into a Church in West part of this Town called New Boston.”

By September 1736, laborers had erected a 68 foot by 54 foot frame, though the building would not be ready for services until spring of 1737. In the meantime, on January 3, 1737, members of the group met at Hugh Hall’s mansion, where they accepted the Church Covenant, confirmed the charter members, and elected William Hooper to be the first minister. Hooper had arrived in Boston around 1734 from Scotland to be a tutor to the son of an aristocratic Bostonian family. He soon was invited by different Congregational clergies to speak from their pulpits, and quickly gained a following for his preaching. His son, William Hooper, would go on to be a member of the Continental Congress and signer of the Declaration of Independence.

The West Church, also called the Lynde Street Meeting House or Boston’s Ninth Church, opened its doors on April 17, 1737, and was deemed “beautiful and commodious” by the congregation. Hooper proved to be a popular, if at times contentious, preacher for the first few years of the Church’s existence, until he shockingly converted to Anglicanism and accepted the pastorate of Trinity Church in 1746.

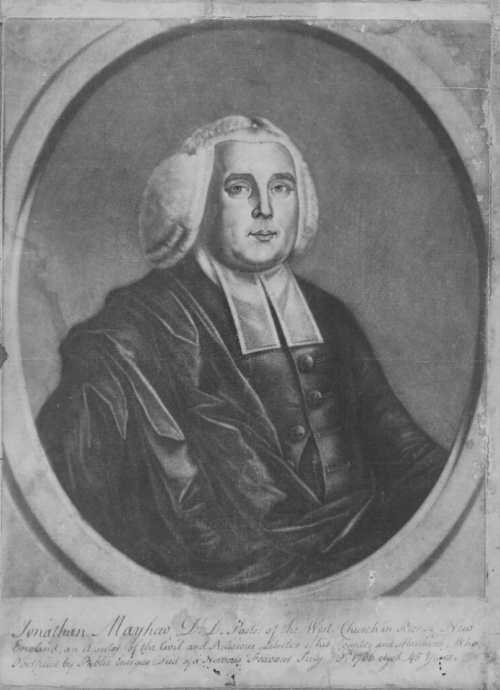

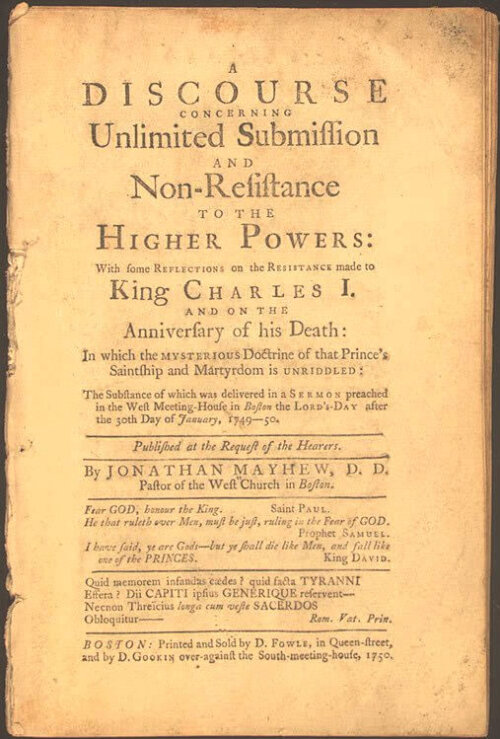

The West Church’s next minister, Jonathan Mayhew, was no less provocative than their first. As minister, Mayhew propagated the principles of natural rights, civil liberties, constitutionalism, and resistance to tyranny. His 1749 sermon (published and disseminated further in 1750), A Discourse concerning Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to the Higher Powers: With some Reflections on the Resistance made to King Charles I, used religious principles to attack the notion that kings were owed absolute submission. In 1765, Mayhew would also take on a leading role in resistance to the British’s Stamp Act. His sermons and writings influenced a number of American revolutionary figures, including John Adams and Robert Treat Paine, who called Mayhew the father of civil and religious liberty in America.

Paul Revere was also part of Mayhew’s West Church congregation, and had multiple of his children baptized there. He first began sneaking away from his family’s congregation, the New Brick or Cockerel Church in the North End, when he was fifteen years old to listen to Mayhew’s “radical” preaching. Revere’s father, Apollos, begged his son to leave Mayhew’s church, which he ultimately agreed to, though he remained a friend and admirer of Mayhew until the minister’s death in 1766.

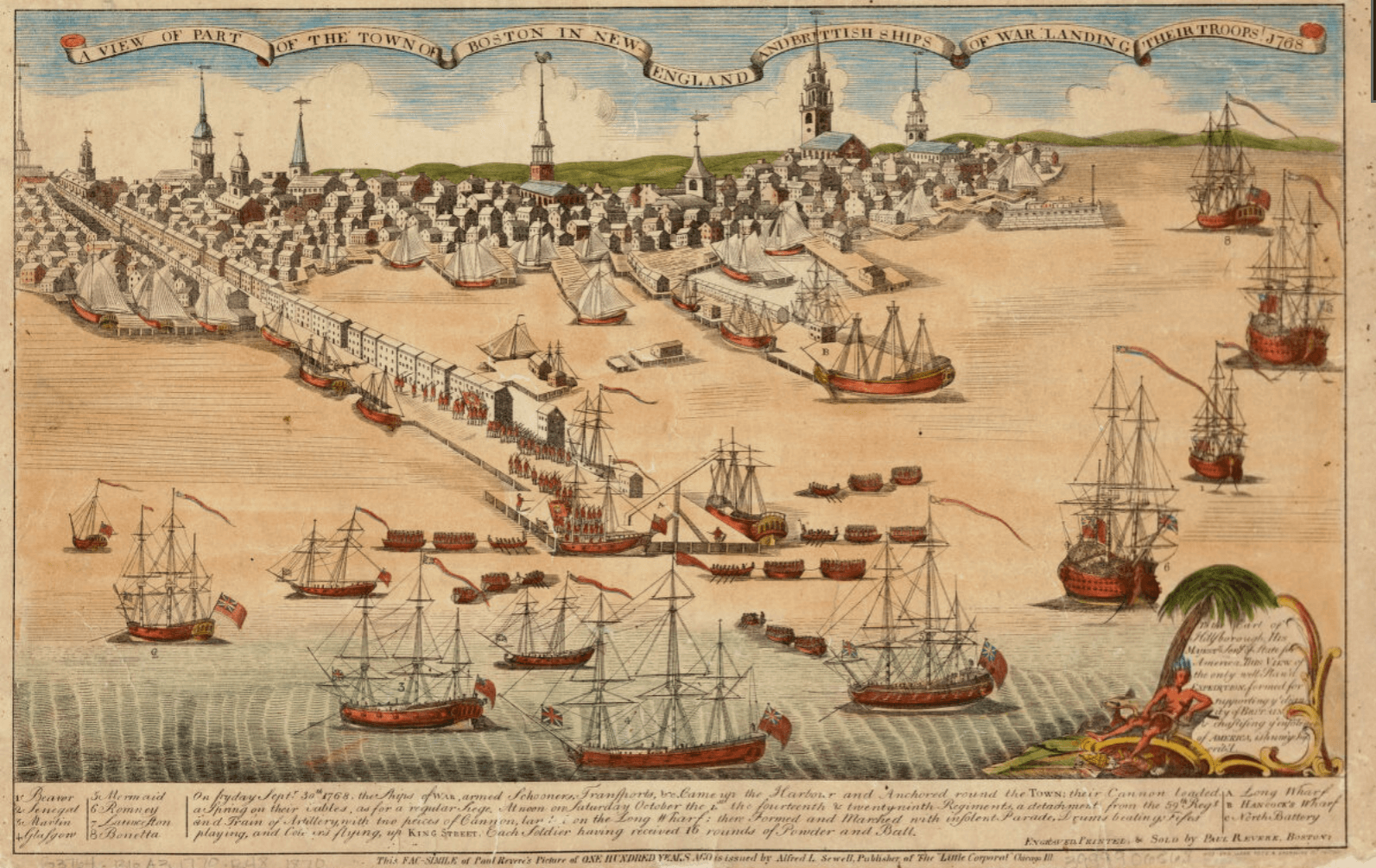

Leading up to the Revolutionary War, West Church was used as barracks by British troops during their occupation of the city. Many other churches befell the same fate: the Hollis Street and Brattle Square Churches lodged redcoats, Old South Meeting House was used to hold their horses, and the First Baptist Church was used as a hospital. In 1775, British forces destroyed the West Church’s steeple, as they suspected that American Patriots were signaling to Cambridge from the spire. Martin Gay, deacon of West Church and a Loyalist, was tasked with protecting the church’s valuables during the British occupation. Deacon Gay filled his secretary desk with the Church’s linen and silver communion service for safe keeping, and brought them to Nova Scotia. Upon his return to Boston in 1792, Gay safely delivered the silver back to West Church.

Severely damaged during the War, the original West Church was taken down and the current Old West Church was built in 1806. Designed by Asher Benjamin, the building served as a church, then a branch of the Boston Public Library (1894-1960), then a church again. Through its various iterations and uses, from West Church to the now-standing Old West Church, this site has witnessed nearly three-hundred years of revolutionary thoughts, sermons, and events.

Article by Grace Clipson, edited by Bob Potenza.

Sources: Charles W. Akers, “The Life of Jonathan Mayhew, 1720-1766,” PhD Dissertation (Boston University, 1952); Charles W. Akers, “Religion and the American Revolution: Samuel Cooper and the Brattle Street Church,” William and Mary Quarterly 35 (1978): 477-98; Jacqueline Barbara Carr, After the Siege: A Social History of Boston, 1775-1800 (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2019); City of Boston, “Community Preservation Act Funds, Saving One Historic Building At a Time”; Colonial Society of Massachusetts, The Records of the First Church in Boston; Samuel Adams Drake, Old Landmarks and Historic Personages of Boston (Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, 1873); Charles C. Farrington, Paul Revere and His Famous Ride (Kessinger Publishing, 2010); Harvard Square Library, “Mayhew, Jonathan (1720-1766)”; Jane Holtz Kay, Lost Boston (University of Massachusetts Press, 2006); Massachusetts Historical Society, “A View of the Old West Church: A Branch of the Boston Public Library. With Mr. Updike’s New Year’s Greetings…1914”; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “Samuel Edwards, Wine Cup”; Joel J. Miller, The Revolutionary Paul Revere (Thomas Nelson, 2010); Lesley Ann Moerschel, “‘In Ye Service of the Lord’: Boston’s Churches, Public Discourse, and the American Revolution,” PhD Dissertation (Washington State University, 2012); National Park Service, “Old West Church”; Out of the Archives, “Martin Gay”; Paul Royster, “Note on the Text: A Discourse concerning Unlimited Submission and Non Resistance to the Higher Powers: With some Reflections on the Resistance made to King Charles I. And on the Anniversary of his Death: In which the Mysterious Doctrine of that Prince’s Saintship and Martyrdom is Unriddled (1750),” Electronic Texts in American Studies 44 (2008); James H. Stark, The Loyalists of Massachusetts and the Other Side of the American Revolution (Genealogical Publishing Company, 2014); Annie Haven Thwing, The Crooked and Narrow Streets of Boston (Harvard University, 1920); C.H. Van Tyne, “Influence of the Clergy, and of Religious and Sectarian Forces, on the American Revolution,” The American Historical Review 19, no. 1 (1913): 44–64.