Jonathan Mayhew

Jonathan Mayhew (1720-1766) was a minister and influential theologian who was a foundational figure in the philosophy that spurred revolutionary sentiment in the colonies. He preached at Old West Church from 1747 to 1766, where he would deliver sermons on politics and share his unorthodox theology.

John Adams described Jonathan Mayhew as “the spark that ignited the American Revolution,” and Robert Paine called Mayhew “America’s Father of Civil and Religious Liberty.” Born on October 8, 1720, to one of the most prestigious New England families, Mayhew was the great-grandson of Thomas Mayhew, the first governor of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket, and the son of Reverend Experience Mayhew.

As a youth, he gave indications of great intellectual ability and reverence for his father’s faith. His father educated him in his childhood, before Jonathan attended Harvard, which he graduated from in 1744. In 1747, he took his position at the West Church in Boston. In the three years between his graduation and his call to the pulpit, he studied with Dr. Ebenezer Gay of Hingham, MA, learning his Unitarian theology. Mayhew was first approached by a church in Cohasset, MA, to become their lead minister but he denied the role so he could continue his studies. Mayhew also received a Doctor of Divinity degree from the University of Aberdeen in 1749.

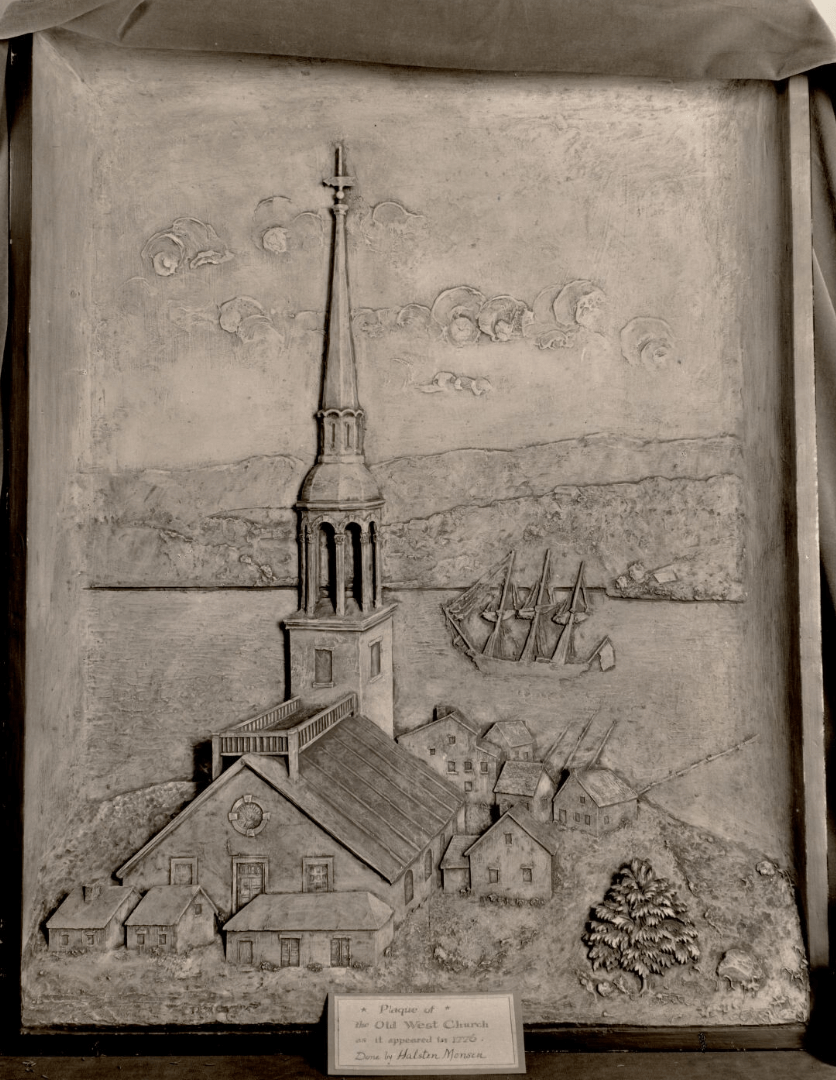

The original West Church congregation was established in 1737 and was widely regarded as the hub of liberal Christian thinking in Boston. The founding minister was William Hooper, whose progressiveness garnered him the label of a heretic from Puritan Ministers. As a result, he withdrew his membership from the Church of England in 1747 and resigned from the congregation. However, Hooper’s school of thought had left an indelible mark on the West Church community, and in choosing Mayhew as his successor, the church continued to challenge the rigid dogma of Puritan Boston.

Mayhew’s ordination was highly irregular, as no Boston minister took part in it and he had already been labeled a heretic before he stepped into the ministerial role at the Old West Church. This criticism stemmed from his background in Arianism and Unitarianism, which he had studied with Dr. Gay in Hingham. On the day of his ordination, only two ministers from the city of Boston showed up. When presented with Mayhew’s theology, they left the church immediately, stalling the beginning of his priesthood. Fortunately, Mayhew gathered a council of 14 ministers from the Boston area who were willing to ordain him into the church. Many of these priests were outside the Bostonian Puritan orthodox beliefs and were eager to see a liberal-minded young preacher begin his service. On June 17, 1747, he began his life’s work.

In mid-18th-century Boston, the Thursday Lecture was a staple of religious life, where members of the Boston Association of Congregational Ministers would gather and speak to the public. Mayhew was denied the opportunity to join this association and, therefore, the Thursday Lecture series. He established his weekly lecture series in response, where he espoused his diverse viewpoints to the masses and led many to leave behind their classical Puritan values and theology.

Mayhew was an Arminian, a theological stance that diverged from the rigid Calvinism predominant in Boston. Arminianism, founded by Jacob Arminius in the 16th century, directly opposed Calvinism’s central doctrine. Calvin emphasized predestination, the idea that because God was all-powerful, God chose who would be saved and who would be damned. In contrast, Arminianism argued that salvation was available to all individuals through their inherent free will. While Arminians believed that God’s grace was necessary for salvation, they stressed the role of human choice in accepting or rejecting God’s grace. Mayhew was also Unitarian, another unique theological viewpoint that set him apart from his peers. Instead of viewing God in three persons, Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, as most sects of Christianity espoused, Mayhew and other Unitarians believed in the oneness of God.

Because of these beliefs, Mayhew was ostracized from the Puritan Boston religious community. His rejection of the Trinity and predestination placed him at odds with the religious authorities. Nevertheless, his commitment to his theology earned him a dedicated following. Through his ministry, Mayhew became a prominent figure in the Boston intellectual community. Through his writings, he could reach many outside his congregation, exposing them to his values of religious freedom, individual conscience, and the separation of church and state.

In all of Mayhew’s writings, both religious and political, he combined the principles of modern liberalism with the Christian faith. These liberal values included freedom of belief and speech, the right to personal conscience, the importance of reason, the separation of church and state, and individual liberty. In connecting this philosophy to religion, he was open to discussion on Biblical interpretation and was opposed to taking everything in the Bible as literal. This combination of beliefs and values made him incredibly impactful on modern Christianity; his ideas continue to influence religious and political discourse today, particularly in the United States.

Mayhew was also one of the first American Whigs or revolutionaries. He had close friendships with Bostonians who would lead the future American Revolution, including James Otis, John and Samuel Adams, James Bowdoin, John Hancock, and Thomas Paine; Mayhew would be instrumental in the development of their American Revolutionary ideas. Through his sermons and writings, Mayhew articulated a philosophy that the American colonists would use to Biblically justify their revolt. His interpretation of Romans 13, a Biblical passage on the conduct of governors and the governed, was the cornerstone of his argument that resistance to tyrannical rule was both justified and a Christian duty.

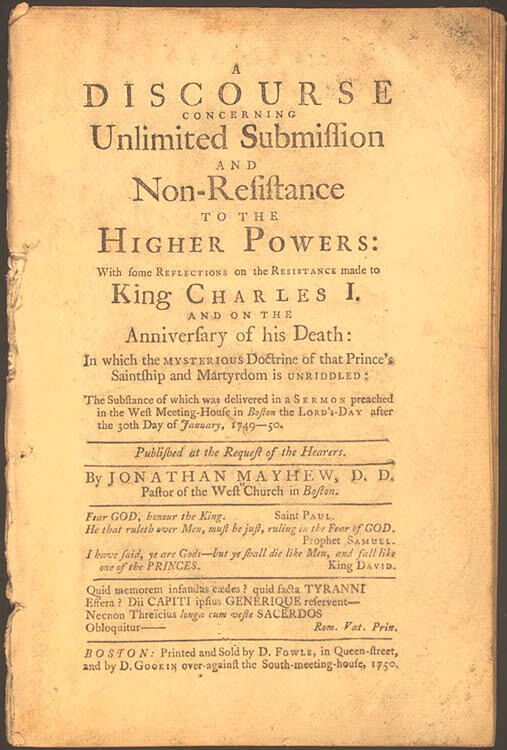

In his 1750 sermon, “Discourse Concerning the Unlimited Submission and Non-Resistance to Higher Authorities,” delivered at a time when the American colonies were increasingly dissatisfied with British rule, Mayhew argued that when rulers become tyrants, they violate their divine mandate. This sermon was groundbreaking, as it provided a religious justification for the American Revolution. His rhetoric and compelling theology galvanized support for a revolutionary spirit.

In June 1766, when Mayhew returned home from an ecclesiastical council, he caught a violent fever and was bedridden shortly after that. He passed away on July 9, 1766, at age 45. He left behind his wife, Elizabeth Clark, and two children. His widow married his successor, Reverend Dr. Simeon Howard.

Yet, Mayhew’s legacy as an influential figure in Boston’s West End carried on far after his death. The Mayhew School was first established in 1803 as the West School or Hawkins Street School for Boys. The school combined with the Derne Street School’s male students in 1830 and, by 1838, had an attendance of 409 students. This led to a second building being added in 1847. However, the school was closed in 1879 and transitioned into a homeless shelter.

The new, and architecturally grand, Mayhew Primary School, was erected in 1897 at 38 Poplar Street (now Chambers Street) by the skilled hands of architect John Lyman Faxon. The new schoolhouse, a three-story structure in an L-shape, was adorned with robust square columns and arches, and was a sight to behold. Inside, the Mayhew School boasted 14 classrooms, with its pièce de résistance being the T-shaped stairway, a striking feature midway between the first and second floors.

The Historic American Buildings Survey described Faxon’s Mayhew School as “the largest and most elaborately detailed building among those to be demolished for the Boston West End redevelopment.” The building was demolished in 1960 as part of the West End urban renewal project.

Article by Kegan Foley, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Encyclopedia Britannica, “Arminianism” & “Jonathan Mayhew”; Gary Galles, “Jonathan Mayhew: America’s First Revolutionary Preacher-Patriot,” Foundation for Economic Education (2019); Harvard Square Library, “Mayhew, Jonathan (1720-1766)”; Frank Moore, The Patriot Preachers of the American Revolution: With Biographical Sketches (New York, New York: C.T. Evans, 1862); Eric Patterson, “Jonathan Mayhew: Colonial Pastor Against Tyranny,” Providence (2020); WEM Archives: Mayhew School; WEM Archives: Historic American Buildings Survey Number 673.