Population Over Time in the West End

A report on the population of the West End from the late colonial period through the modern day.

The West End has grown and changed since the founding of Boston in 1630, before the American Revolution in 1776 and the incorporation of Boston as a city (before, a town) in 1822. The West End was a relatively small and isolated part of Boston in the late 1700s, when the neighborhood had less than 2,000 residents.[1] But observers wrote that it was a nice place to live then. Nathaniel Shurtleff, the nineteenth mayor of Boston who became a historian, commented in 1871 that before the 1800s, “New Boston, the West End, contained…one meeting-house and about one hundred and seventy dwelling houses and tenements; and, although the smallest and least populous of the divisions [of Boston], was regarded then as a very pleasant and healthy part of the town…”[2] The West End’s population increased rapidly in the 1800s with new arrivals from many countries. Irish immigrants moved into the West End after 1846 to escape Ireland’s brutal potato famine. Immigrants from Italy and Eastern Europe followed in waves, up until World War One, to seek a better life.[3]

The West End’s population peaked in the early 1900s and mostly declined since then. Historians and economists report different estimates for when the West End’s population peaked, and how large it was at that point. Economist Frederick Bushee wrote in a 1903 publication that the West End had 34,500 residents in 1900.[4] If true, this would be the only year when the West End had 30,000 or more residents. At the neighborhood’s height, the population fluctuated between 28,000 (in 1895) and 23,000 (in 1910). From 1920 to 1950, the West End’s population decreased from 18,500 to 12,000 residents. Relocation to the suburbs or different neighborhoods of Boston, and the effects of the Great Depression and World War 2, contributed to the long-term decline in the West End’s population.

Population Over Time in the West End

| 1742 | 1,204 |

| 1770 | 1,456 |

| 1895 | 28,000 |

| 1900 | 34,500 |

| 1910 | 23,000 |

| 1920 | 18,500 |

| 1930 | 13,000 |

| 1940 | 13,000 |

| 1950 | 12,000 |

| 1958 | 7,900 |

| 1970 | 2,500 |

| 1980 | 4,014 |

| 2000 | 4,221 |

| 2017 | 6,173 |

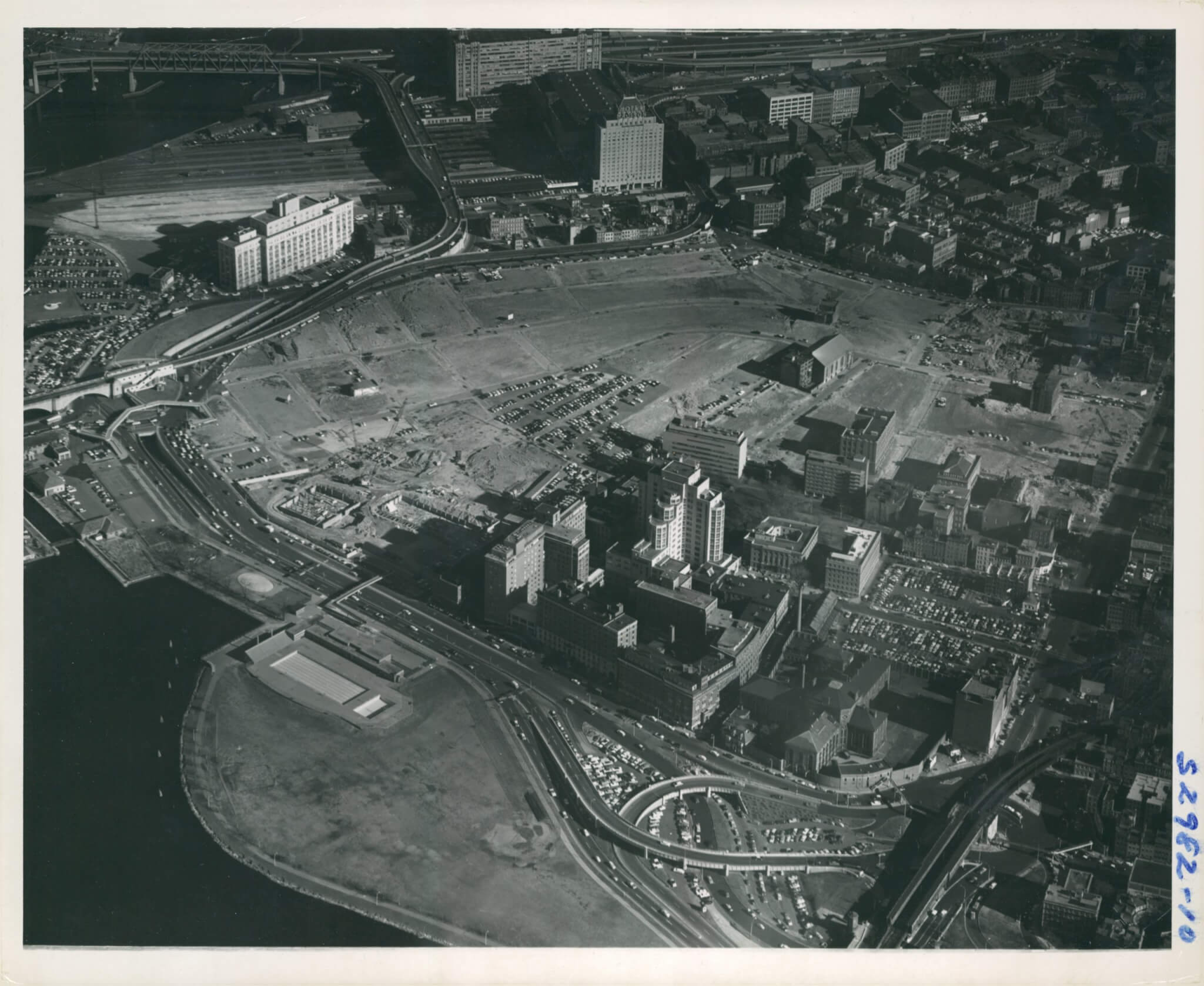

The West End’s demographics were also affected by the Boston Redevelopment Authority’s announcement, in 1951, that it would demolish most of the old West End. In 1956, the West End had 11,000 residents; that number decreased to 7,900 by 1958, shortly before demolition.[5] Many West Enders left the neighborhood when its destruction appeared inevitable, and fewer people moved into the West End for the same reason. The West End’s population was stable when people moving out (as they naturally do) were replaced by a nearly equal number moving in, but this could not hold with the BRA’s announcement of urban renewal. But many West Enders fought for the preservation of the neighborhood and were determined to stay, even when demolition was imminent.[6]

The West End’s population has seen an upward trend after urban renewal, but the numbers are nowhere near what they once were. The West End went from having 2,500 residents in 1970 to 6,173 residents in 2017.[7] The total population of Boston, for reference, was 695,926 in 2018.[8] Comparing the population size of the old West End with today’s West End is useful for a number of reasons. Most importantly, we can precisely understand how urban renewal achieved one of its objectives, the reduction of population density (number of people per square mile, typically). But we can also reflect on the stark contrast in the numbers, knowing that the West End’s population today is far less than half of what it was 100 years ago. Reformers of our past, such as Jane Jacobs, remind us that the large population of the West End at its peak may have been a testament to the neighborhood’s vibrancy and also a contributor to it.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source:

[1] Allan Kulikoff, “The Progress of Inequality in Revolutionary Boston, The William and Mary Quarterly 28:3, July 1971, pg. 394. JSTOR.

[2] Nathaniel B. Shurtleff, A Topographical and Historical Description of Boston (Boston: Rockwell & Churchill, 1871), pg. 139.

[3] William D. Warner. “Residential Redevelopment of the West End of Boston.” Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Architecture at The Massachusetts Institute of Technology. May 21, 1956, pg. 3.

[4] Frederick Bushee, “The Invading Host,” in Robert A. Woods (ed.), Americans in Process: A Settlement Study by Residents and Associates of the South End House (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1903), pgs. 40-41. HathiTrust.

[5] Marc Fried, Ellen Fitzgerald, Peggy Gleicher, et al., The World of the Urban Working Class (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973), pgs. 48-50. HathiTrust.

[6] Marc Fried, Ellen Fitzgerald, Peggy Gleicher, et al., The World of the Urban Working Class (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1973), pg. 51. HathiTrust.

[7] United States Federal Highway Administration, “Third Harbor Tunnel, I-90/Central Artery, I-39, Boston, Environmental Impact Statement,” 1985, pg. 69, Google Books. Boston Redevelopment Authority, “Boston’s Shifting Demographics,” July 2015, http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/5b407528-bf69-4c01-83b9-d2b757178e47/

[8] Boston Planning & Development Agency, “Boston at a Glance – 2020,” accessed January 22, 2021, http://www.bostonplans.org/getattachment/d3deed32-9044-4abb-9bfa-d23803489b65