Faces & Places: LGBTQ+ History in the West End

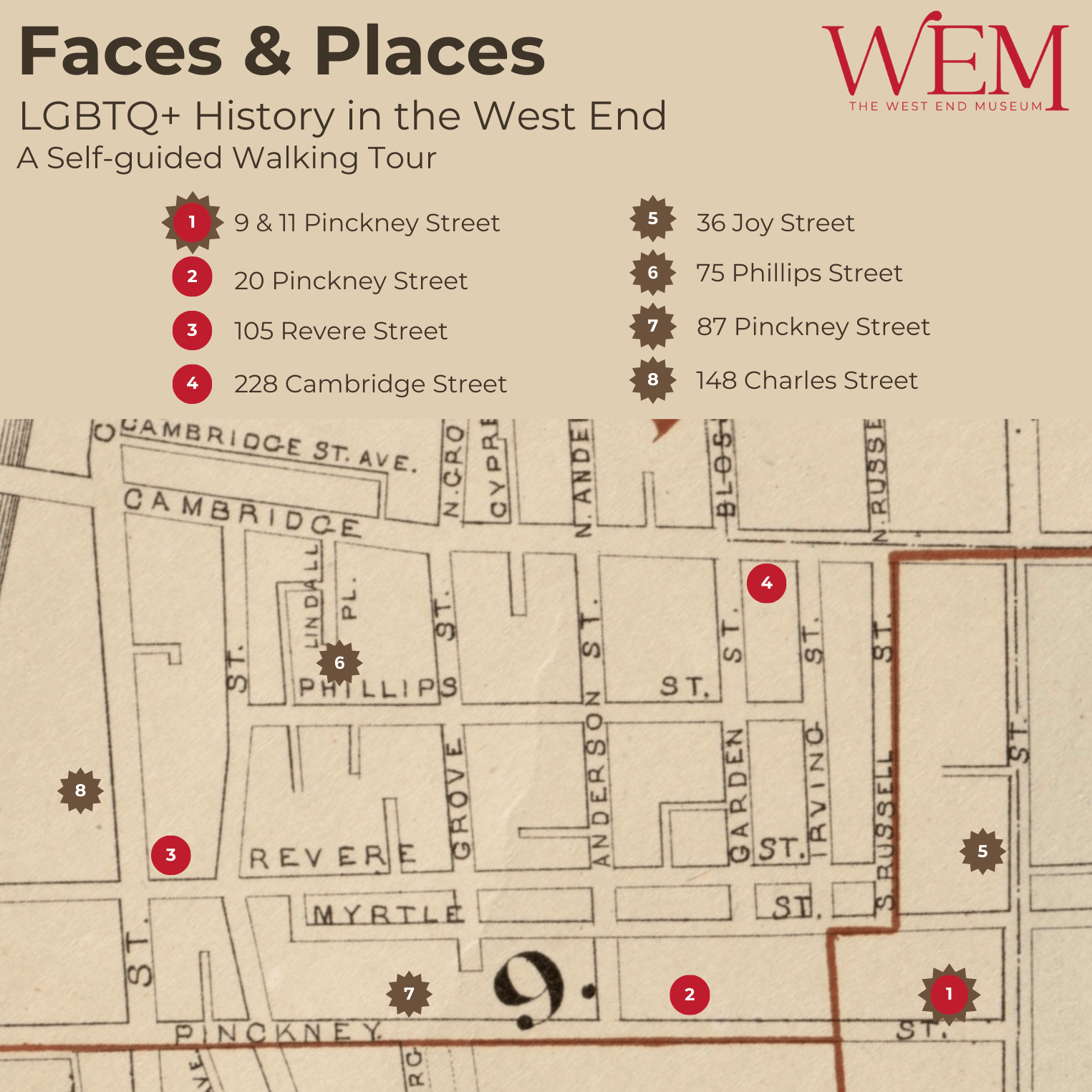

This is a self-guided version of our Faces & Places: LGBTQ+ History in the West End walking tour. From the late nineteenth century onward, this neighborhood was a hub for LGBTQ+ people in Boston, even when much of their history and activities flew under the radar. This area featured speakeasies, raids, Boston marriages, early publication of queer literature, famous gay bars, and AIDS epidemic protests. This tour will focus on the faces and places of the queer community in the West End and how they shifted over time.

Below is an online, self-guided version of our Faces & Places: LGBTQ+ History in the West End walking tour. If you would like to print out the tour before your walk, please see our printable version using the link below.

Links to Canva versions: Printable version, version with clickable links, map (with legend) only

Thank you for following this self-guided version of Faces & Places: LGBTQ+ History in the West End – A Walking Tour today! This tour stops at four locations on the north slope of Beacon Hill to look at LGBTQ+ history in the West End before its period of urban renewal. There are also three bonus stops at the end, if you want to extend your tour.

Please note: if you are following the self-guided tour, you may proceed directly to Stop 1 without visiting the West End Museum – but you may wish to visit the museum before your tour to get familiar with the history of the neighborhood.

The individuals mentioned on this tour fall under the LGBTQ+ umbrella, defined by the Human Rights Campaign as: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and a plus sign to indicate “the limitless sexual orientations and gender expressions used by members of the community.” We have tried to use specific terminology as used by the individual where possible.

Stop 1: 11 Pinckney Street – Louise Imogen Guiney & Alice Brown

This corner of Pinckney was home to a number of interesting folks around the turn of the century. The writer, Alice Brown (1857-1948) lived in 11 Pinckney around the 1890s. She was a novelist, and her best known work was Stratford by the Sea (1884). She had an intimate romantic friendship with a poet named Louise Imogen Guiney (1861-1920), author of Songs from the Start (1884) and A Roadside Harp (1893). Guiney often visited Pinckney Street to visit Brown, and her other friend, the photographer F. Holland Day, who lived at 9 Pinckney Street around the same time.

In addition to their romantic friendship, Guiney and Brown founded the Women’s Rest Tour Association (WRTA) in 1891. The aim of the WRTA was to provide helpful tips for women traveling alone in Europe, such as where to stay and visit, at a time when single women were thought to require “protection” from men — financially as well as physically — while traveling. The WRTA helped women subvert gender expectations and exert independence while traveling both by themselves and with female companions for many decades.

While you are here, why not read about F. Holland Day, resident of 9 Pinckney Street?

Stop 2: 20 Pinckney Street – Louisa May Alcott

Louisa May Alcott (1832-1888), author of Little Women, lived at 20 Pinckney Street with her family from 1852 to 1855. Her room was on the 3rd floor, and while living here, she sold her first story, “The Rival Painters: a Tale of Rome,” and her first novel Flower Fables. Alcott scholar Gregory Eiselein feels that Louisa May Alcott did not fit a “binary sex-gender model.” For example, she preferred being called Lou or Louy, she referred to herself as “papa” or “uncle” to her nephews, and her father Bronson Alcott once called her “his only son.” Other scholars point to the beliefs of the Transcendentalists, the philosophical circle to which her father belonged, that human beings were spirits who happened to take a particular physical form. This could have influenced Louisa’s approach to gender as impermanent and flexible, not tied to her human form. When interviewed in 1883, she said, “I am more than half-persuaded that I am a man’s soul, put by some freak of nature into a woman’s body…because I have fallen in love in my life with so many pretty girls and never once the least bit with a man.” It is difficult to ascribe modern terminology to Louisa May Alcott’s sexuality and gender identity, but suffice it to say that she cannot be described as simply a woman.

Stop 3: 105 Revere Street – Lee Porter

During World War I, the Navy was preoccupied with preventing same-sex relationships among its men. The house at 105 Revere street was one node of a network of investigations that blanketed the East Coast. On October 20, 1918, undercover investigators from the Navy came to this house because they had heard rumors that sailors were coming here to cavort with other men. Witnesses testified that the owner of the house, Lee Porter, had brought men here and there were stories about drag shows with men wearing kimonos and a ceremony where the men cursed the police for harassing gay people. Porter was arrested as a result of the investigation, but he was found not guilty of sodomy in his first trial. In a second trial, he was found guilty of running a house of ill repute and sentenced to one year in prison at Deer Island House of Corrections. He appealed, claiming that the second trial violated the Double Jeopardy Clause, but his conviction was upheld. By 1922, he had moved to Europe, and we don’t know what happened to him after that.

Stop 4: 228 Cambridge Street – Sporters

A bar called Sporters operated at 228 Cambridge street for nearly six decades. It opened in 1939 and became “officially” gay in 1957 — meaning that the owners and staff embraced the majority gay clientele and it became known as a gay-friendly space. Sporters’ heyday occurred in the 1960s and 1970s, partly because it drew in university students from Harvard and MIT on the Red line. Sporters was discrete, with an unmarked facade, and incurious local residents may have had no clue what was going on inside unless someone was in the know. The gay bar scene in Boston at this time provided a much needed refuge for the city’s LGBTQ+ population. Folks who did not feel safe coming out at home or work could express their identities openly without risking stability in their everyday lives.

Sporters’ rise in popularity in the 1960s was also due to the demolition of Scollay Square by 1963. Scollay Square, located just up Cambridge Street where City Hall is now located, had been a hub of entertainment through the first half of the 20th century, full of bars, restaurants, and theaters. It was especially known for its burlesque shows and was a popular destination for sailors on leave. After World War II, it became a hub for local gay bars, but it was also falling into disrepair.

The locations of gay bars played a role in urban renewal in Boston. City councilman Fred Langone, a North End resident and former member of the Committee to Save the West End, was well known for his commitment to saving the city’s downtown neighborhoods from destruction. But when the South Cove neighborhood tried to fight back after their gay bars’ liquor licenses were revoked in 1965, Langone declared, “We will be better off without these incubators of homosexuality and indecency and a Bohemian way of life. I tell you right now, we will be better off without it and if we accomplish nothing else, at least we will uproot this cancer in one area of the city.” The queer community in Boston felt the effects of urban renewal, as did the immigrant families displaced from the tenements. In the 1960s, popular gay bars across the downtown area closed, but new bars opened regularly in neighborhoods like the South End and Fenway, which are two areas still generally associated with the gay community in Boston today.

Extend Your Tour

If you would like to extend your tour, read these articles from the West End Museum at these locations on the north slope.

5) 36 Joy Street & 6) 75 Phillips Street: Prescott Townsend

Prescott Townsend (1894-1973) founded the first social group of gay men in Boston and was a lifelong gay rights advocate in Massachusetts. He lived on the north slope from the 1920s to the end of his life.

7) 87 Pinckney Street: F. O. Matthiessen

F.O. Matthiessen (1902-1950) was an influential literary critic and Harvard professor who lived with his life partner Russell Cheney on the north slope in the 1940s.

8) 148 Charles Street: Boston marriages

Annie Adams Fields (1834-1915) and Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909) were partners in a Boston marriage for nearly three decades. They lived primarily on Charles Street in the historic West End.

By focusing on the pre-renewal period, this tour has only scratched the surface of LGBTQ+ history in the West End. There is still more to explore in the future such as: the general history of Scollay Square, Massachusetts General Hospital and the AIDS crisis, the Metropolitan Community Church at Old West Church, the gay bars of Bulfinch Triangle in the 1990s, and more. If you are interested in learning more about LGBTQ+ history in the West End, please let WEM know so we can include more programming in the future!

Article by Emma Beckman, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Joan Acocella, “How ‘Little Women’ Got Big,” The New Yorker, August 20, 2018; Scott Bane, A Union Like Ours: The Love Story of F. O. Matthiessen and Russell Cheney (University of Massachusetts Press, 2022); Lucious Beebe, Boston and the Boston Legend (New York: D. Appleton-Century, 1935); Boston Evening Globe, “Degrees Awarded at Harvard Commencement,” June 20, 1918, Vol XCIII, No. 171; Adrian Cathcart, Adrian, Queer for Justice: An Autobiographical Memoir by Prescott Townsend (unpublished, 1995); Commonwealth v. Porter, 237 Mass. 1 (Mass. 1921) 129 N.E. 298; Alfred H. Cutler, “Down Memory Lane,” The West Ender, March 1993, Vol. 9, no. 1 (West End Museum Digital Archive);Sarah Deutsch, “The Moral Geography of the Working Girl (and the New Woman),” in Women and the City: Gender, Space, and Power in Boston, 1870-1940 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000); Lillian Faderman, “Boston Marriage,” in Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love between Women from the Renaissance to the Present, 190–203 (New York: Morrow, 1981); Lillian Faderman, “Social Housekeeping: The Inspiration of Jane Addams,” in To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999); Patricia J. Fanning, “F. Holland Day and ‘the Beautiful Boy’: The Story of Thomas Langryl Harris and Day’s Nude Study,” History of Photography 33, no. 3 (June 29, 2009): 249–61; Patricia J. Fanning, Through an Uncommon Lens: The Life and Photography of F. Holland Day (University of Massachusetts Press, 2008); Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, “Biography | Whitman Archive,” The Walt Whitman Archive; Randall Fuller, “Aesthetics, Politics, Homosexuality: F. O. Matthiessen and the Tragedy of the American Scholar,” American Literature 79, no. 2 (June 1, 2007): 363–91; Herbert J. Gans, The Urban Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian Americans (New York: The Free Press, 1962); Mark Herz, “In a Neighborhood That Once Shunned Him, a Boston Gay Rights Pioneer Finally Gets His Moment,” GBH, June 19, 2023; Robert Hillyer, Review of Review of Boston and the Boston Legend, by Lucius Beebe, The New England Quarterly 8, no. 4 (1935): 601–3; Louis Hyde, ed, Rat & the Devil: Journal Letters of F. O. Matthiessen and Russell Cheney (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1978); Estelle Jussim, Slave to Beauty: The Eccentric Life and Controversial Career of F. Holland Day, Photographer, Publisher, Aesthete (Boston: Godine, 1981); Robert Kenney, “South Cove Branded Degenerates’ Hangout,” Boston Globe, July 8, 1965; Harry Levin, “The Private Life of F.O. Matthiessen,” The New York Review of Books, July 20, 1978; Emily Levine, “Alice Brown,” Boston Athenaeum, May 4, 2016; LIFE, “Red Visitors Cause Rumpus,” April 4, 1949; Theo Linger, “Prescott Townsend,” National Parks Service; Tom Long, “Frederick C. Langone, at 79; Colorful Boston Councilor,” Boston Globe, June 26, 2001; Russ Lopez, The Hub of the Gay Universe: An LGBTQ History of Boston, Provincetown, and Beyond (Boston: Shawmut Peninsula Press, 2019); “Mattachine Society Boston Area Council Newsletters,” n.d. Box 1, folder 7, Boston Athenaeum Prescott Townsend Papers and Photographs, 1906-1997; Meg Metcalf, “Research Guides: LGBTQIA+ Studies: A Resource Guide: The Mattachine Society”; John Mitzel, “Beans, Cod and Libido: The Life of Prescott Townsend, 1894-1973,” Manifest Destiny, Summer 1973, No. 3. Box 1, folder 10, Boston Athenaeum Prescott Townsend Papers and Photographs, 1906-1997;Chadwick Moore, “I’m Not Psycho: John Waters’s 50th Summer in Provincetown,” OUT Magazine, July 31, 2014; Carol L. Nigro, “Annie Adams Fields: Female Voice in a Male Chorus,” Ph.D., Georgia State University; Poetry Foundation, “Louise Imogen Guiney”; Rouse, Wendy L. “Queering Domesticity,” in Public Faces, Secret Lives: A Queer History of the Women’s Suffrage Movement, 37–65 (NYU Press, 2022); Ralph Saya, “The Jolly Roger,” The West Ender, September 1993, Vol. 9, no. 3 (West End Museum Digital Archive); Charles Shively, “Prescott Townsend (1894-1973): Bohemian Blueblood – A Different Kind of Pioneer,” in Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context, edited by Vern L. Bullough (Oxford, UK: Taylor & Francis Group, 2002); Adam Sonstegard, “‘Bedtime’ for a Boston Marriage: Sarah Orne Jewett’s Illustrated Deephaven,” The New England Quarterly 92, no. 1 (2019): 75–108; “Sporters,” U.S. National Park Service; The Harvard Crimson, “Eliot Book Room Exhibits Treasures,” February 19, 2002; The Harvard Crimson, “F. O. Matthiessen Plunges to Death from Hotel Window,” April 1, 1950; The Harvard Crimson, “Matthiessen Heads Union,” May 16, 1940; The History Project, Improper Bostonians: Lesbian and Gay History from the Puritans to Playland (Boston: Beacon Press, 1998); Peyton Thomas, “Opinion | Did the Mother of Young Adult Literature Identify as a Man?” The New York Times, December 24, 2022; Margaret Farrand Thorp, Sarah Orne Jewett – American Writers 61: University of Minnesota Pamphlets on American Writers, NED-New edition (University of Minnesota Press, 1966); Prescott Townsend, “Letter from Prescott Townsend to Tony and Curtis,” February 17, 1959, Box 1, folder 7, Boston Athenaeum Prescott Townsend Papers and Photographs, 1906-1997; University of New Hampshire Library, “Guide to the Alice Brown Papers, 1876-1947,” December 14, 2007; Jodie Noel Vinson, “The Unprotected Females of the Women’s Rest Tour Association,” The Massachusetts Review 58, no. 1 (2017): 136–47; Randolfe Wicker, “Boston’s Bohemian Blueblood,” GAY Magazine, December 1, 1969, Box 1, folder 11, Boston Athenaeum Prescott Townsend Papers and Photographs, 1906-1997; Randy Wicker, “Xmas Letter 1994,” 1994, Digital Transgender Archive.

1 Comment