The Boston Museum

In an age of ongoing Puritan restrictions on theatrical shows, Moses Kimball founded the Boston Museum as a venue which bowed to the cultural aspirations and respectability of mid-19th Century Boston, but at the same time gave the people what they wanted; live performances. Before the renowned Howard Athenaeum (and later the Old Howard) had opened its doors across the square, the Boston Museum attracted large audiences to the Scollay Square area to witness music, drama, and even moral instruction on stage.

The Boston Museum (originally the Boston Museum and Gallery of Fine Arts) was founded by Moses Kimball (entrepreneur, politician and associate of P.T. Barnum) in 1841 at 18 Tremont Street on the corner of Bromfield Street. The Museum’s ground floor served as the Exhibition Hall while the second floor was the Portrait Gallery, which could also be used as an auditorium. Containing mostly items from the purchase of the New England Museum, the Exhibition Hall displayed hundreds of paintings, engravings, watercolor drawings, statuary, Chinese artifacts, and taxidermies of birds, elephants, and giraffes. The Portrait Gallery contained paintings of presidents, Massachusetts governors, clergymen, and naval commanders. The Boston Museum, however, provided more than just an intellectual experience. Kimball, leveraging his knowledge of local law, was able to provide his customers with theatrical entertainment, while still adhering to the strict Puritan laws of the day.

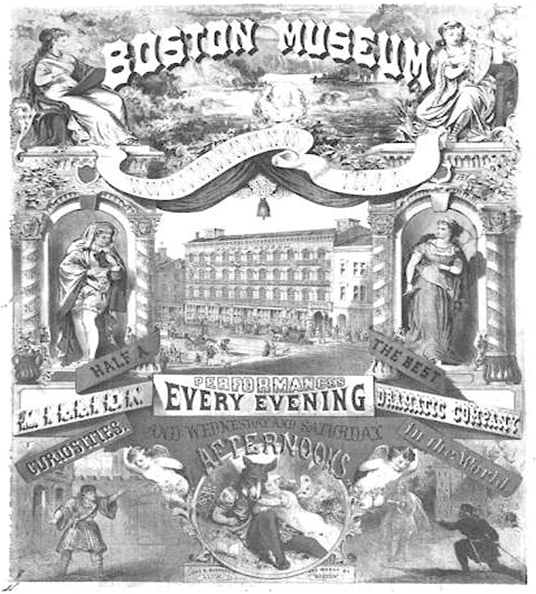

After paying the admission fee of twenty-five cents, visitors to the Boston Museum had access to all of its exhibits and galleries, but could also head upstairs to the auditorium to enjoy a music olio (a form of vaudeville act), birch bark whistling, or other mild-mannered performances which the city censors would not view as ungodly. Later the Museum added acts such as juggling and gymnastics, educational demonstrations such as fancy glass working, and technical exhibits, such as a pneumatic railroad. For those visitors who preferred not to be regarded as theatre-goers, this variety of cultural entertainment protected their reputations if seen going through the Museum’s doors. Even as the Boston Museum later became more theater than museum, it continued to lend the impression that people were attending something more than a mere playhouse.

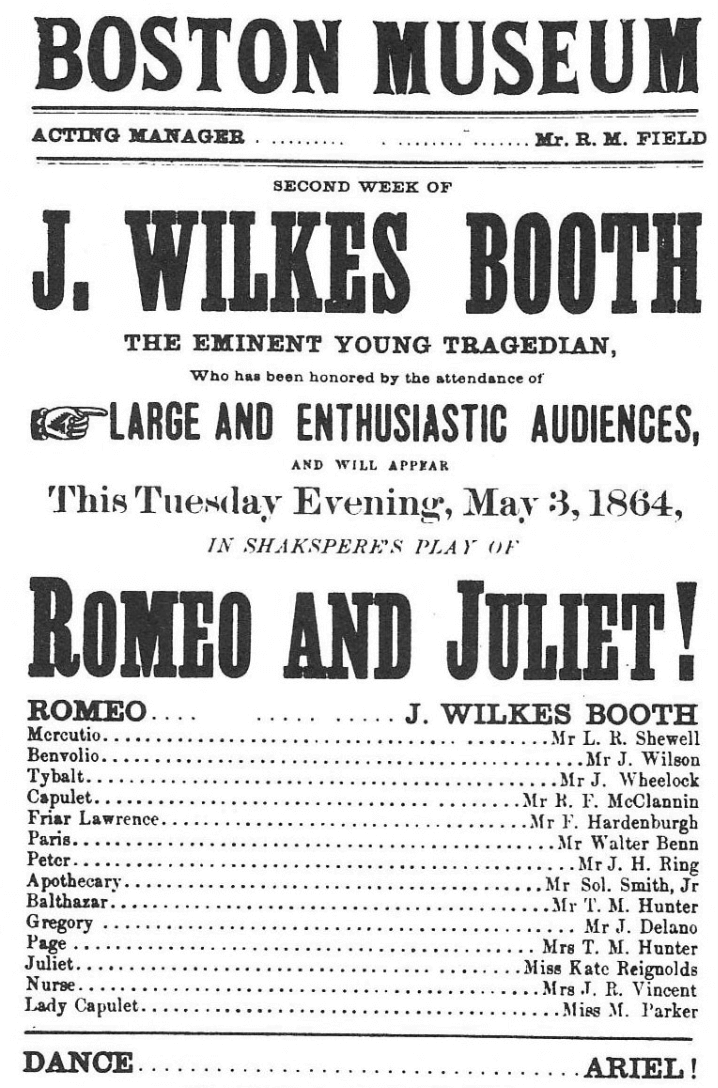

In subsequent seasons, the Boston Museum introduced operettas and stage plays. Those first evening shows included two or three short plays with interludes in between. Plays performed at the Boston Museum consisted mainly of dramas, vaudevilles, pantomimes and spectacles. Shakespeare was an audience favorite, especially Richard III and Romeo and Juliet, both of which were presented frequently. Other popular shows were Sheridan’s, The School for Scandal, and the English drama The Lady of Lyons. The admission fee for the theater was kept low and audiences could return on the same daily ticket to watch their favorite shows.

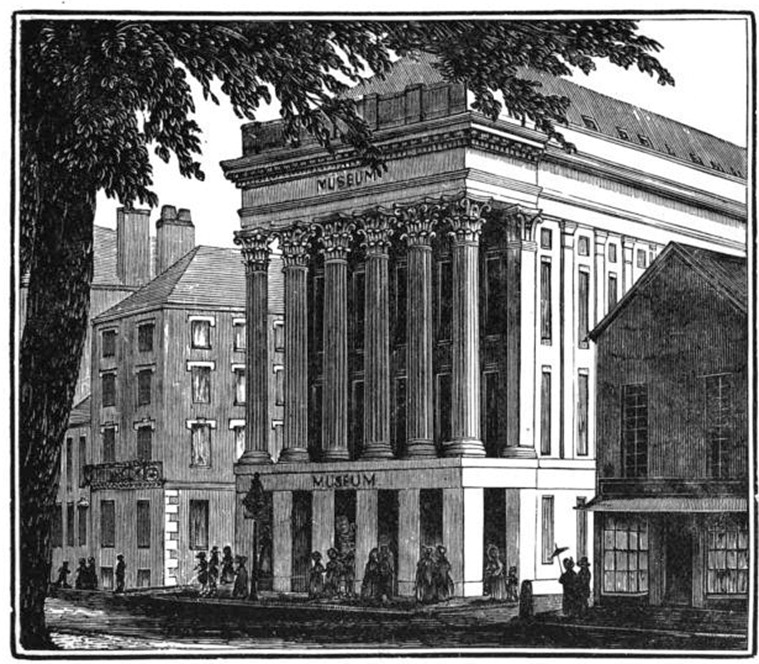

In 1846, five years after its opening, the success of the Boston Museum forced it to find a larger, more suitable venue. Kimball had a new building erected at 28 Tremont Street, still on the eastern border of Scollay Square and close to what would be his greatest rival, the Howard Athenaeum. Like its rival across the square, the Boston Museum found it needed to bring in big name actors to compete. One popular Shakespearean actor of the day, John Wilkes Booth of Maryland, made the rounds at both the Boston Museum and the Howard Athenaeum, as did members of his acting family. Booth starred in the leading role of Romeo and Juliet at the Boston Museum less than a year before shooting President Abraham Lincoln.

In addition to artistic performances, Kimball presented moral plays reflecting contemporary social movements in the city. During the nineteenth century, the temperance movement had widespread support in Boston. Kimball capitalized on this opportunity by offering a play titled The Drunkard, which turned out to be so popular that it ran for over a hundred performances; a feat unheard of for any theater at the time. Other moral plays included The Gambler, a study of the evils of gambling (another vice that the city wished to eradicate). These moral plays drew in audiences who typically did not associate with the theater, such as Reverend John Pierpont, a prominent clergyman and advocate of temperance, and diverted attention away from its more lively shows.

Moses Kimball’s clever inclusion of the moral with more common artistic plays, not only served to improve his box office sales by attracting more varied audiences, but also provided a public service, and reinforced the moral image of the theatre. This philosophy allowed The Boston Museum to stay open for sixty years, even under the vestiges of Puritanical law, before finally closing its doors in 1903. While in operation, it served as a gallery and a theater, providing entertainment, education, and fond memories for its visitors and employees long after its closing.

Article by Queenie Chen, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: https://www.bostonathenaeum.org/library/electronic-resources/boston-athenaeum-theater-collection/history, McGlinchee, Claire. First Decade of the Boston Museum (Bruce Humphries, INC. 1940); Ryan, Kate. Old Boston Museum Days (Little, Brown, and Company. 1915)