The Howard Athenaeum

Between 1845 and 1961, the Howard Anthenaeum served as a center of performances for a wide variery of clientele. Beginning its life as an upper-class theater, it became a legendary venue for minstrel shows and burlesque until it was demolished as part of the Government Center urban renewal project.

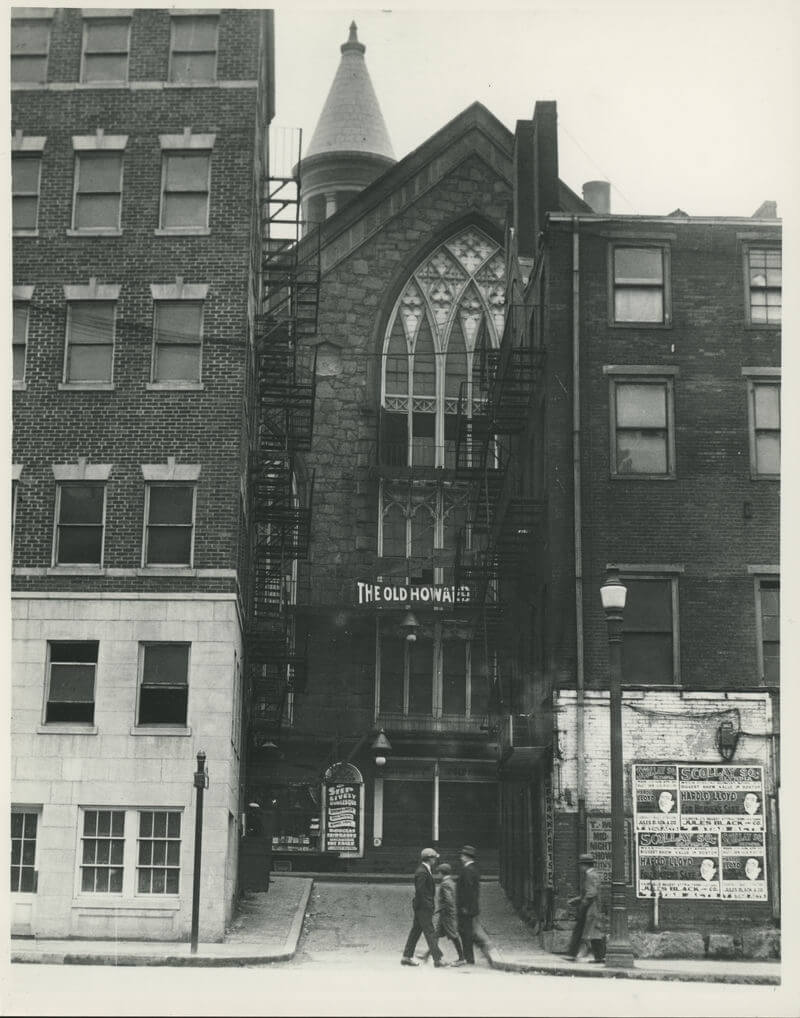

The Howard Athenaeum, later known as the Old Howard, was once the most prominent theaters in Scollay Square (now Government Center). Its original structure was built in 1843 to serve as a church for the Millerites — a Christian millennialist sect who believed the end of the world was imminent. When, in 1844, the day of the millennium came, the Millerites sold their positions and prepared for a rapture that never came. The sect disbanded and the Howard was left unoccupied. A year later, in 1845, the building reopened as a theater that operated continually from that date until a fire in 1961, which was followed closely by demolition of the building as a part of the Government Center urban renewal project. By the time of its destruction the Old Howard had undergone repeated changes, served a variety of audiences, and hosted a wide range of performances.

The Howard Athenaeum opened on October 13, 1845 with Sheridan’s School for Scandal, a comedic play first performed in London in 1777. The theater enjoyed full houses for several months after opening, until a fire on February 23, 1846 destroyed most of the Howard’s wooden stage. The theater remained empty for several months while architect Isaiah Rogers redesigned the interior. When the Howard reopened with its new and improved installations it became the first Boston theater to have cushioned seats and newly added balcony and orchestra sections allowed for different ticket prices based on seating; however, those seating options came with a black mark. The Howard was the only theater in Boston to enforce racial segregation of its guests in this period. Within a week of its reopening the Howard had soared in popularity to the point that there were scalpers selling tickets for its shows. During the remainder of the mid-1800s, the Howard hosted Italian grand operas, the first American ballet performance of Giselle, Shakespearean plays, and more. At this time, most of its offerings were targeted for upper-class Bostonians; however, by the end of the century the Howard’s audience had changed, as had its performances.

Until the late 1800s, the residential areas around the Howard Athenaeum were occupied by wealthy Bostonians. Residences, including the grand dwellings in Pemberton Square and the still-extant bowfront row houses on Bowdoin Street, where Boston Associates — an expanded group that included both Brahmins (e.g. the Coolidges and Winthrops) and great industrial families such as the Lowells) — lived. By the 1880s, however, newer neighborhoods such as the South End and Back Bay had attracted the majority of Boston’s elite. Meanwhile, massive influxes of Irish immigrants, who had already filled East Boston and the North End, took up residency in the vacated South and West Ends (the South End collapsed socially as Back Bay was completed). As a result, businesses in Scollay Square, including the Howard, adapted to their new clientele. The price of tickets decreased, and instead of operas and ballet performances the Howard now hosted minstrel shows and pantomime supplemented with special events such as the Human Fly, Tony Pastor’s comedic company, and John L. Sullivan’s boxing matches. These acts soon returned the Howard to its place as the most popular theater in Boston, and its management constantly brought in new forms of entertainment to keep audiences engaged. The first movie screen was installed at the Howard 1912 and in the 1920s chorus girls, stripteases, and burlesque shows became the dominant acts on its stage. Large groups of men and women enjoyed these shows and a midnight Ladies’ Show allowed women to attend without escorts. By the 1930s, the Howard had become the place of entertainment for the common people, and caught the attention of the Watch and Ward Society.

The Watch and Ward Society was a private group formed in 1884 with the mission of upholding public morality in the Bostonian tradition of secular Puritanism. The Society deemed the Howard’s burlesque and striptease performances as immoral. After badgering the city to shut down the venerable theater, they finally succeeded in closing the Howard for thirty days in 1933. In those thirty days, however, businesses in Scollay and Bowdoin Squares — such as hot dog stands, penny arcades, and lunchrooms — suffered dramatic declines in revenue, and complaints flooded the mayor’s office, which ensured that the Howard would reopen. For the following two decades, the Howard became something of a legend in show business. Many popular stars of the time such as Abbott and Costello, Phil Silvers, and Milton Berle had started their careers at the Howard, and visiting the theater became a staple in the lives of sailors, businessmen, and students. During World War II, the theater and its surroundings were so popular that “How are things in Scollay Square?” became an unofficial call sign for US ships in the Atlantic signaling that they were American.

Many Bostonians have fond memories of skipping class to watch performances at the Howard — where a schoolboy could go for a midday movie and stick around until the dancers came on in the afternoon. The importance of the Howard for many Bostonians generated numerous efforts to save it from demolition in the 1960s. In 1959, the Howard National Theater and Museum Committee was formed to save the Howard from the wrecking ball of urban renewal. The committee wanted to convert the Howard into a national shrine that would continue to host operas and plays, but before their plans could be finalized, the Howard suffered two fires that left little of the theater for the committee to work with. Many people believe that the fires were the result of arson meant to ensure an urban renewal payout for the building’s owners. In the end, the Howard was demolished to make way for the new Government Center. Today a 1968 plaque in One Central Plaza marks its location, and elements of the structure survive at the Emerson Umbrella in Concord and The West End Museum.

Article by Queenie Chen, edited by Sebastian Belfanti & Robert Potenza

Source: David Kruh, Always Something Doing: A History of Boston’s Infamous Scollay Square (Faber and Faber, 1989); Cinema Treasured; State Library of Massachusetts; Boston Globe (January 26, 1908, page 23); Boston Globe (February 5, 1961, page 113); Boston Globe (June 21, 1961, page 25); The West End Museum Archives; Horton & Horton, Black Bostonians (Holmes & Meier, 1979)