The Rise and Fall of Jewish Life in the West End

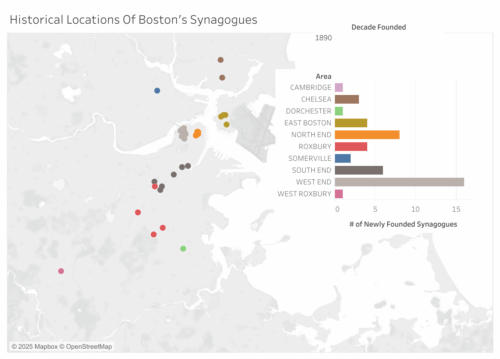

At its peak, the vibrant West End neighborhood was home to approximately 40-45 synagogues, reflecting the thriving Jewish community that once defined the area. Today, only the Boston Synagogue remains as the sole continuously-operating Jewish house of worship in the neighborhood while the historic Vilna Shul, built in 1919, now serves a center for Jewish arts and culture.

Immigration Transforms the West End

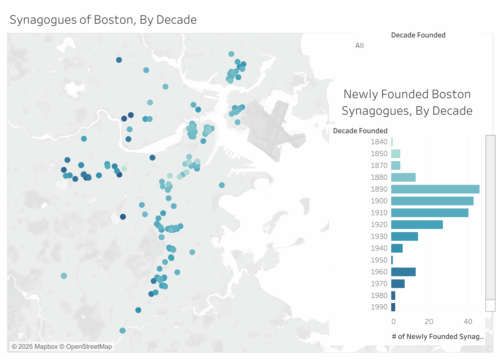

Boston’s West End underwent a cultural and demographic transformation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, evolving from a peripheral rural area into a densely-populated immigrant neighborhood. Originally dominated by Irish immigrants who comprised the majority by 1850, the West End’s demographic composition shifted dramatically between 1880 and 1910. During this period, Eastern European Jews—primarily from Russia, Poland, and Lithuania—became the largest new immigrant group, eventually constituting about 25% of the West End’s population. They joined a diverse neighborhood that included Italians, Poles, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, and Hungarians, creating what became one of Boston’s most ethnically diverse districts.

The migration pattern of Jewish immigrants followed a distinct path through Boston. Jews followed the Irish, first settling in East Boston, and then in the North End, where from 1885 to 1900 it became a predominantly Jewish neighborhood. Soon, they expanded out of the North End into the West End, where most new Jewish arrivals settled. These immigrants largely came from central and eastern Europe—from Russia, Poland, Ukraine, Hungary, Austria, and Romania.

The influx of Jewish immigrants occurred during a massive wave of Eastern European immigration, with Boston’s Jewish population expanding dramatically. Between 1875 and 1925, an estimated 50,000 to 70,000 Jewish immigrants arrived and settled in Boston, with many initially making their homes in the North and West Ends.

The Flourishing of Synagogue Life

In response to this new population, the West End quickly developed cultural sites and institutions that would allow “traditional [Hebrew] life to flourish.” The neighborhood soon housed ten synagogues, kosher butcher shops, groceries, and even a mikvah (ritual bath).

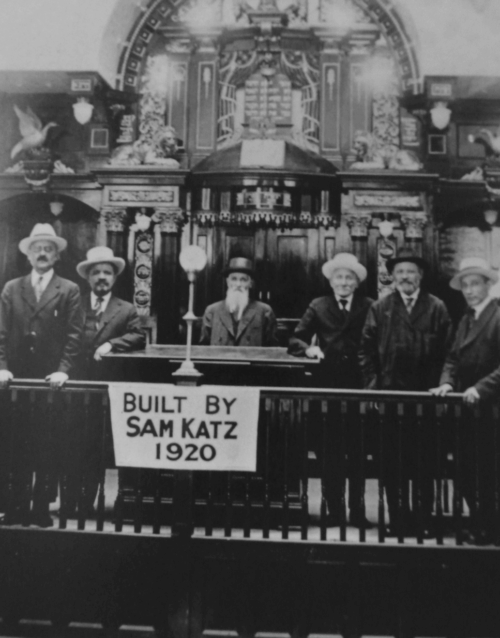

The cultural and spiritual life of the West End’s Jewish community was anchored by its synagogues. At its height around 1910-1920, approximately 20-25 synagogues operated simultaneously in the neighborhood, with the total number of individual congregations reaching 40-45 over time. Most were founded between 1888 and 1920. These synagogues represented an estimated 17 different Jewish religious traditions, reflecting the diverse origins of the immigrant population. While larger synagogues like the one on North Russell Street served as central hubs for Jewish life, many smaller congregations met in storefront shuls or even private homes. Common locations included Poplar Street, Lowell Street, Leverett Street, Chambers Street, and Minot Street.

The North Russell Street synagogue emerged as “the center of Jewish life in the West End,” hosting numerous fraternal lodges, such as the Sister of Rebecca and B’rith Abraham, as well as charitable organizations. These synagogues functioned not only as religious centers but also as cultural and social hubs, operating immigrant banks, burial societies, and various charitable initiatives.

Changing Places: Black Churches Becoming Synagogues

One of the most fascinating aspects of the West End’s religious history was the transfer of buildings between the earlier African American community and the growing Jewish population. By the 1890s, large numbers of African Americans were leaving the West End, with leaders of the Twelfth Baptist Church, an African-American church, noting in 1905 that the north slope of Beacon Hill had been “deserted” by Black people and had become “congested by a Hebrew population.”

This demographic shift led to the phenomenon of African American churches being sold to Jewish congregations. In 1900, the historic African Meeting House, built in 1806, was sold to Congregation Anshe Libavitz (also written as Libovitz/Lebovitz/ Lubavitch/Libawitcz). This was followed by the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church on North Russell Street becoming a synagogue, and the Twelfth Baptist Church on 45 Phillips Street (previously Southac Street) being purchased by the Vilna congregation in 1906. In 1919, the first stones were laid for Vilna Shul’s new and current location down the street at 18 Phillips Street. As a contemporary observer noted, “the change in the ownership of this building within so recent a time registers the curious social displacement that is coming about in that part of the West End.”

Economic Success and Property Ownership

The Jewish community’s growing prominence in the West End was reflected in their increasing economic success, particularly as measured by real estate ownership. A glance at several selected streets from 1885 to 1905 reflects not only the changing ethnic composition of the West End but also the degree of Jewish economic success. In 1885, Jews owned no real estate on either Hale or Poplar Streets. By 1895, they owned 55% and 26% respectively; by 1905, their percentage of ownership had risen to 62% and 56%.

That year, they constituted the majority of real estate owners in the district’s population mix of Jews, Italians, Irish, and Americans. Both the Irish and the Americans posted a decline in the percentage of property owned between 1885 and 1905. On Poplar Street, American ownership dropped from 88% to 19%, while in the same period Irish ownership dropped from 12% to 8%. These figures indicate an out-migration of the older groups.

By the turn of the century, Jews were the largest minority in the West End, although they made up only 25% of the area’s population. Writing in 1903, the social observer Frederick Bushee claimed that the Jews had “already taken almost exclusive possession of the northern part of the West End.” They would continue to dominate it for several decades until migrating to Dorchester, Mattapan, and Roxbury.

Community Relations and Ethnic Diversity

Until their migration to other neighborhoods, Jews of many nationalities shared the West End with Italians, Poles, and other Eastern Europeans. The relationship between these diverse immigrant communities was complex. While Jewish cultural values might have facilitated integration with Boston’s elite Brahmins and promoted a rapid socioeconomic rise, relations with other ethnic groups in the West End were not always friendly.

Jacob M. Burnes, director of the West End House for 40 years, when writing of his turn-of-the-century childhood experiences, noted that many were the “royal battles waged between the sons of Erin and those of Israel.” These battles were at their best when street construction was occurring, for here was “ammunition aplenty.” Basketball games also served as a mechanism for working out antagonisms, a tradition that continued into the 1950s.

The growth of the Jewish community in the West End occurred alongside the Italian migration to Boston’s neighborhoods. In 1880, there were approximately 125 Italians in the West End and about 1,000 in the North End, with about 100 Jews found in both districts. 15 years later, there were 6,300 Jews and 1,100 Italians in the West End. Frederick Bushee hypothesized that the large influx of Jews was in response to the Italian saturation of the North End.

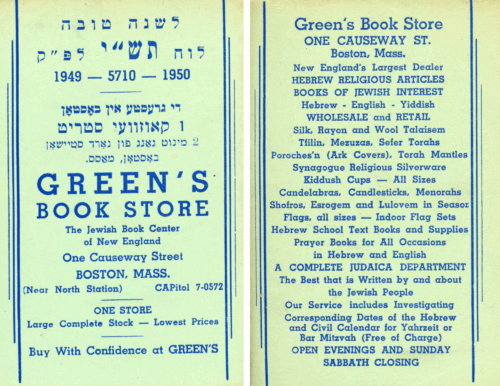

Community Infrastructure Beyond Synagogues

Beyond religious institutions, Jewish life in the West End was supported by various social service organizations. The Hecht House, founded by philanthropist Lina Frank Hecht in 1889, provided vocational training for Jewish girls and later expanded to serve boys as well. Under the direction of Golde Bamber, it offered numerous programs for the children of Eastern European Jewish immigrants.

Leonard Nimoy, the actor best known for his role as Mr. Spock on Star Trek, grew up in the West End and provided vivid testimony about daily life in the neighborhood: “There was a street called Spring Street, which was where most of the Jewish shops were, and the shopkeepers there all spoke Yiddish. So my grandmother, if she wanted to shop, never had to speak English—never had to worry about the language. She could go and do all her business in Yiddish. It was really a village life.” Nimoy’s recollections also highlight the fascinating cultural exchanges that occurred between the neighborhood’s ethnic groups: “Before refrigerators, we had an icebox, which meant that it was a box with two compartments. The top compartment was where they put the ice—a block of ice. The bottom compartment was where all the food went. We had an iceman who put a block of ice on his shoulder and came up two or three flights. He was an Italian who spoke Yiddish. He learned to speak Yiddish because he had a lot of Yiddish-speaking customers. So it was that kind of a crossover relationship. The Italians spoke Yiddish, the Jews spoke Italian—some did.”

In 1903, Mt. Sinai Hospital was established on Staniford Street. They provided medical care that respected Jewish customs (e.g., kosher food) and employed Yiddish-speaking physicians. The hospital was supported by the Federation of Jewish Charities and the Ladies Auxiliary led by Lottie Feibelman.

Decline and Diaspora

After World War I, the pattern began to reverse as Jewish West Enders started dispersing to the more suburban districts of Roxbury, Dorchester, and Mattapan. This migration accelerated through the 1920s and 1930s, while the Italian population in the West End grew. By the 1950s, the neighborhood had become predominantly Italian-American.

The movement of Jews from the West End was reflected in the history of its synagogues. Many congregations merged between 1916 and 1925, with larger institutions like the “United Congregation Beth Jacob” forming through multiple mergers. Others simply relocated to Roxbury and other neighborhoods where Jewish families were moving. By 1960, the Boston Synagogue (Charles River Park Synagogue) was established as a successor to earlier congregations, including Beth Hamidrash Hagadol, Anshei Lubavitch, Anshei Sfard, and Beth Yakov. Today, it remains the only continuously-operating synagogue in the West End, while the historic Vilna Shul on the northern slope of Beacon Hill (previously in the West End, prior to border changes) now functions primarily as a cultural center.

The final blow to the West End and its synagogues came with the city’s first major urban renewal project in the late 1950s, which razed much of the neighborhood and transformed it beyond recognition. This urban planning decision effectively ended the area’s role as a vibrant immigrant district, dispersing its remaining ethnic communities and erasing much of its architectural heritage. The story of the West End’s synagogues mirrors the broader narrative of American Jewish immigration, community building, and eventual suburbanization—a pattern repeated in many American cities throughout the 20th century.

Article by Amir Tadmor, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Boston College Department of History, “The West End,” Global Boston; Carol Clingan, Massachusetts Synagogues and Their Records, Past and Present (Jewish Genealogical Society of Greater Boston, Inc., 2010); Sean M. Fisher and Carolyn Hughes, The Last Tenement: Confronting Community and Urban Renewal in Boston’s West End (The Bostonian Society, 1992); The West End Museum, The Last Tenement Exhibition (Bostonian Society); Northeastern University, Digital History of the Jews of Boston; The Pluralism Project at Harvard University, “Vilna Shul”; Yiddish Book Center, “Leonard Nimoy Remembers Boston’s West End Neighborhood.”