The Angels' Flight from the Hill: Urban Renewal in L.A.’s Bunker Hill Neighborhood

The area of Bunker Hill in downtown Los Angeles has a rich history. It started as a rugged sandstone highland overlooking a river plain. Later it transitioned from a wealthy residential enclave to a diverse mixed-use community. Like the West End, the Bunker Hill neighborhood was targeted for an urban renewal project in 1958. The city demolished the Hill and the housing on top of it to make way for high-rise buildings. This urban renewal project displaced at least 8,000 individuals. Today, its history is under reevaluation.

In the mid-1800s, Los Angeles earned the nickname “Hell Town” for being rough, lawless, and dusty. The city was almost abandoned in the 1860s after a devastating cycle of drought and flooding destroyed cattle ranches. What came to be known as Bunker Hill was a natural rise of land that loomed over the town of under 5,000 people.

Locals considered the land of the steep hill useless. Seeing possibility, however, French Canadian immigrant Prudent Beaudry, later the Mayor of Los Angeles, began purchasing acreage. He had a plan to subdivide it. The Hill was named either for the Revolutionary War battle or for the forts dug into the side of the hill by the Mormon Battalion in 1847 (or a bit of both). Bunker Hill Avenue ran along the top of the hill by 1873. Beaudry surveyed and planned lots and devised a reservoir and pump system for water delivery. He sold parcels and construction began. Those who could afford it sought to rise above what was becoming a busy city.

The years between 1886 and 1889 were a boom time for Los Angeles. The population grew and building expanded. Queen Anne style mansions joined folk Victorian and Italianate homes along the top of the Hill. The newest homes were a display of prosperity and ingenuity. They had modern conveniences of steam heat and hot water, gas and electricity, and flushable ceramic toilets connected to municipal wastewater systems.

The prominent citizens of the Hill used horse carriages to descend downtown. Yet, they needed a more efficient mode of transportation. The steep Third Street Tunnel and Angels Flight were built in 1901. The latter was an example of a funicular, a type of cable railway that travels up a steep incline. Angels Flight, the world’s shortest railway, took residents up and down the Hill on its 33% grade. The exclusive character of Bunker Hill was largely maintained though the end of World War I.

By the mid-1920s the homes and residents of the Hill had aged. By the 1930s many of the wealthiest Bunker Hill residents had moved from the neighborhood into fashionable new suburbs. Several once-grand mansions were subdivided into boarding houses and affordable apartments. The population became more dense, diverse, and working-class. It was a lively neighborhood. The residents were a mix of retirees and young transplants from Mexico, indigenous reservations, Europe, and the mid-West.

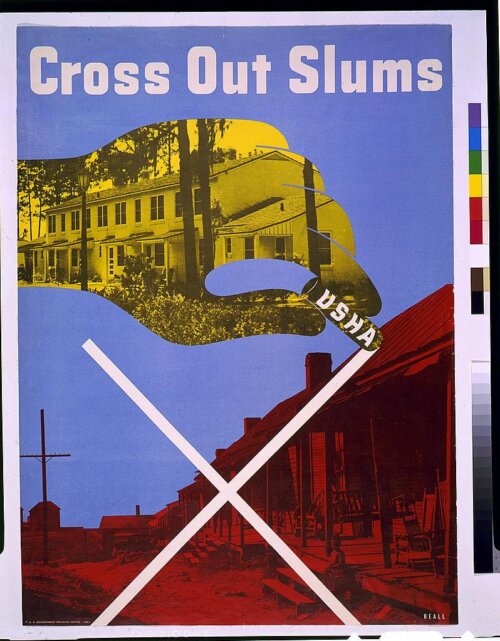

Though it was still a vital, vibrant neighborhood at the end of the Depression, the city government had begun labeling Bunker Hill as “blighted.” Los Angeles was putting plans in place for its transformation. The California Community Redevelopment Law of 1945 and the 1949 Federal Housing Act both allowed for a looser use of eminent domain. Thus, the City Council saw a path for renewal.

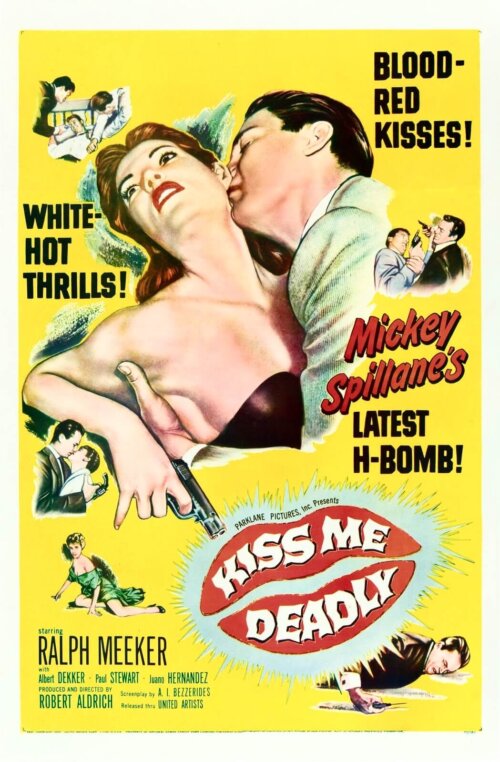

By the end of World War II, Bunker Hill had gained a reputation for being a colorful yet deteriorating neighborhood. It was depicted in film noir movies like Criss Cross and later, Kiss Me Deadly. Many who didn’t live there imagined it as a shadowy world of steep stairways, flickering neon, crime, and decay.

In 1955, the Los Angeles health department declared the neighborhood a health hazard. City planners decided that Bunker Hill required a massive slum clearance project. They would turn the land over to private developers. In 1959, the City Council adopted the Bunker Hill Urban Renewal Project to, “keep our city from slipping backward, like San Francisco and New York in the population race.”

Opponents pushed back against the project with protests and lawsuits. Eventually, the government acquired every property on the Hill through eminent domain. Residents were evicted and the neighborhood razed. Engineers regraded and flattened the Hill itself, erasing its distinctive topography. A few of the large Victorian homes were saved and relocated to Heritage Square, but they were lost to arson. Records show that 7,310 housing units were demolished and at least 8,000 people were displaced.

Redevelopment plans envisioned a modern financial district with skyscrapers, corporate towers, and cultural institutions. It would be an urban landscape optimized for cars, offices, and entertainment. Clearance was fast, but building was slow. Union Bank Plaza, completed in 1968, was the first modern skyscraper built. From the plan’s adoption in 1959, the transformation of the neighborhood took over fifty years to complete. Today, with its many music venues, theaters, and museums, the neighborhood is considered a civic and arts district.

Bunker Hill’s erasure is often cited as a case study in displacement and lost heritage. The few surviving elements—like Angels Flight, restored in the 1990s—serve as nostalgic symbols of what was lost. Public photographs stored at the Los Angeles Public Library and oral histories challenge the narrative of urban decay that justified Bunker Hill’s demolition. Recently, there have been greater efforts to explore the human impacts of urban renewal. What are the implications of projects like this for generations of people? How do scholars separate these stories from architectural and political history?

In 2021, The University of Southern California Libraries, Special Collections, and Archives launched Bunker Hill Refrain. The project explores the true and complex story of the neighborhood. To reach this goal, USC libraries use public history, digital experimentation, and community outreach. They plan to deepen public understanding of urban renewal’s human impact through community-engaged research and scholarship.

Along with greater community engagement, the project tells a more accurate story of Bunker Hill. One of the outcomes will be the creation of an immersive 3D model incorporating archival data and oral histories. The 3D model will allow participants to “walk” the neighborhood as it was before renewal. Much like Boston, home to another Bunker Hill, the city and its people have begun to recognize urban renewal’s lasting human impacts and the importance of preserving the memory of neighborhoods destroyed in the name of progress.

Article by Janelle Smart, edited by Jaydie Halperin.

Sources:

Angel’s Flight Railway; Sebastian Belfanti, “Eminent Domain, Part 3: Urban Renewal to the Present” and Exhibits, “The Beginning of the End: The Housing Act of 1949”, The West End Museum; Kim Cooper, “Meet George Mann”, On Bunker Hill , blog, May 30, 2010; Greg Fischer, “Downtown History: The Big Life of Prudent Beaudry: Remembering an Early Mayor and Major Landowner of Downtown” (Downtown Los Angeles, December 2, 2011); Nathan Marsak, Bunker Hill Los Angeles: Essence of Sunshine and Noir. (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 2020); Carolina A. Miranda, “Bunker Hill once was a neighborhood. Then progress came to town,” Los Angeles Times, 22 May 2019; Los Angeles Public Library Digital Collections “Lost Architecture – California –Bunker Hill”; Christina Rice, Bunker Hill in the Rearview Mirror: The Rise, Fall, and Rise Again of an Urban Neighborhood. Curated by Christina Rice and Emma Roberts. (Los Angeles: Photo Friends Publications, 2016); Paul R. Spitzzeri, “No Place Like Home at 3rd and Hill, LA, ca. 1890”, The Homestead Museum, July 23, 2016; University of Southern California, “Bunker Hill Refrain”, “3D Reconstruction” ; University of Southern California Libraries – LA as Subject .