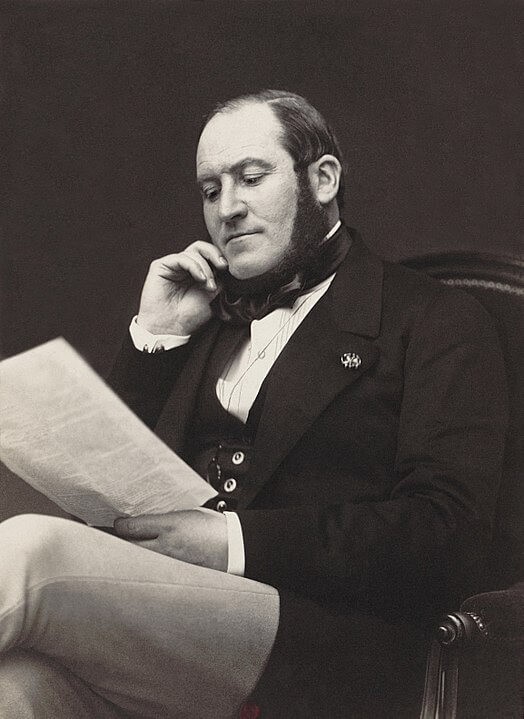

Baron Haussmann

Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann created modern Paris through ambitious urban renewal projects over almost 20 years (1853-1871), but he displaced thousands of working-class Parisians through demolition and slum clearance.

Urban renewal in Boston has a world historical connection to comparable developments in France. Between 1857 and 1880, architect Arthur Gilman redeveloped the Back Bay with wide, tree-lined streets; this design was directly inspired by the plans of Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann for the urban renewal of Paris between 1853 and 1871. Both projects had the same mixed motivations, to contain the spread of cholera (particularly with increased natural light and air) while enabling the rich to live apart from immigrants and the poor. Haussmann in particular was responsible for the displacement of thousands of working-class Parisians from the city’s downtown, after the demolition of their homes left them doubly excluded by rising rents. Looking back at Haussmann’s decisions further deepens the long history of urban renewal around the world, and the fundamental transformations of cities which have lasting effects into the present.

Baron Haussmann had been a civil servant in Paris since 1831, rising to the position of prefect (representative) of the département of the Seine (Paris and its neighboring suburbs around the Seine River) by 1853. As Haussmann advanced through government, he helped orchestrate the French state’s repression of popular protests and himself was against the Republic as a system of government. Also in 1853, Emperor Napoleon III (a nephew of Napoleon I) appointed Haussmann to direct the urban renewal of Paris. Paris still had many medieval buildings and high-density areas connected by narrow streets. Working-class people lived together in conditions typical of nineteenth-century cities: stench and disease, particularly from sewage running down the streets. The wealthy looked down on the neighborhoods of Paris’ “dangerous and laboring classes” because of these conditions, but there were also political efforts to improve those conditions. When Napoleon III was elected France’s first President in 1848, his platform included the ambition of creating a sanitary city for all people regardless of socioeconomic status. But when he appointed Haussmann to redesign Paris, the prefect had much darker intentions than just making Paris a healthier place to live.

Haussmann had no experience in urban planning or architecture, but he likened himself as an “artist-demolitionist.” In his memoirs, he spoke positively of his participation in the “gutting of Paris.” Haussmann led the construction of new parks, squares, and sewers, even new fountains and an aqueduct. But he also demolished 100,000 apartments in 20,000 buildings, including the house that he was born in (on 55 rue de Fauborg-du-Roule, in 1809). Many of these apartments were in neighborhoods that Haussmann designated as slums. According to writer Jess McHugh, Haussmann’s slum clearance in eastern and central Paris had displaced “thousands of people from their homes in exchange for the equivalent of a few dollars.” Former residents could not move back into their neighborhoods because rents increased substantially as Paris catered more to tourists and the wealthy. The displaced moved into suburbs such as Belleville, which Haussmann had also annexed and incorporated into Paris. Haussmann also crudely remarked, in defense of his slum clearance plans, that “it is easier to cut through the center of the pie than through the crust.” The result of Haussmann’s ‘cutting through the center’ was that Paris’s neighborhoods became more economically segregated, where beforehand the rich and poor often lived on the same streets or even in the same buildings.

Haussmann had also replaced many of the narrow streets of Paris with the wide boulevards that the city is famous for today. This was ostensibly to curb the spread of cholera by bringing more air and light into public thoroughfares; the wider streets also facilitated the creation of France’s first department stores. But Haussmann was especially interested in using urban planning to repress protests against the French government. Narrower streets were much easier for workers to block up with barricades, constructed by piles of spare furniture, cobblestones, wood, and waste. The French military, sent in to suppress rebellions, often found it difficult to navigate troops and cannons through the narrow streets. Haussmann saw wider streets as ‘barricade-proof,’ and he even constructed some boulevards to provide the quickest access to areas with the most frequent riots. Haussmann explained his twin goals of imposing order for the regime, and improving public health, to a municipal commission in 1855:

To break through this habitual center of riots so as to cross the rue de Rivoli at a right angle with a new strategic roadway; to bring air and light into the midst of this human anthill; to replace these nearly uninhabitable constructions with healthy and spacious houses, doesn’t that respond to the triple needs of security, circulation, and good health?

Haussmann’s plans to redesign Paris continued for almost 20 years, until he was fired by Emperor Napoleon III in 1870 due to public concerns about Haussmann’s financial mismanagement. When Haussmann was let go, his plans remained unfinished and left the city of Paris with a large debt. While the National Assembly allocated some tax revenue to Haussmann’s plans, he also took on large loans from his own contractors and then relied on “proxy bonds” backed by those loans. Paris accrued a debt of 2.5 billion francs from Haussmann’s projects by the 1860s, though he only managed to raise 500 million francs from his schemes. For historian John Merriman, “the financing strategy was rather like a balloon mortgage that could burst at any time.” Emperor Napoleon III would have kept Haussmann in his position had he not faced serious opposition to Haussmann’s decision-making from the liberal opposition in parliament, which achieved a majority in the 1870 elections.

Haussmann died in 1891 while living on the island of Corsica. He was responsible for the largest voluntary urban planning efforts (not required by rebuilding after a war) in European history. But “the man who created Paris” (in the words of Jonathan Glancey) was also responsible for the mass displacement of working people from the neighborhoods that defined Old Paris – an important history of the underside of progress.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Sources: Britannica; John Merriman, Massacre: The Life and Death of the Paris Commune (2014; ProQuest); BBC; Lapham’s Quarterly; West End Museum